A student uses a digitizer to record geometric morphometric sites on a skull. Credit: NC State University

Researchers are using skeletal evidence to shed light on the migration patterns that led to the Roman Republic conquering most of the Mediterranean world.

Anthropologists from North Carolina State University and California State University, Sacramento have examined skulls dating from the first and third centuries A.D. from three imperial Roman cemeteries. Using new-age forensic techniques they were able to learn more about the Roman Empire.

The researchers examined 27 skulls from Isola Sacra on the coast of Central Italy, 26 from Velia on the coast of southern Italy and 20 from Castel Malnome on the outskirts of Rome. The remains found in Isola Sacra and Velia were from middle-class merchants and tradesmen, while the remains from Castel Malnome belonged to manual laborers.

“We found that there were significant cranial differences between the coastal communities, even though they had comparable populations in terms of class and employment,” Ann Ross, a professor of anthropology at NC State and co-author of the paper, said in a statement.

Samantha Hens, a professor of biological anthropology at Sacramento State and lead author of the paper, explained why there may be differences.

“We think this is likely due to the fact that the area around Velia had a large Greek population, rather than an indigenous one,” Hens said in a statement.

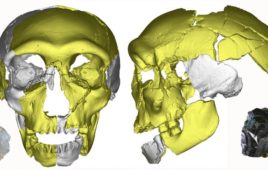

The researchers used a digitizer—an electronic stylus that records the coordinates of each point—to take measurements of 25 specific points. This allowed the researchers to perform shape analysis on the skulls, relying on geometric morphometrics—a field of study that characterizes and assesses biological forms.

The researchers found that the skulls found inland had more in common with both coastal sites than either coastal site had with each other.

“This likely highlights the heterogeneity of the population near Rome, and the influx of freed slaves and low-paid workers needed for manual labor in that area,” Hens said. “The patterns of similarities and differences that we see help us to reconstruct past population relationships.

“Additionally, these methods allow us to identify where the shape change is occurring on the skull, for example, in the face, or braincase, which gives us a view into what these people actually looked like.”

According to Ross, it has been difficult to pinpoint information about many facets of the Roman empire.

“Researchers have used many techniques–from linguistics to dental remains–to shed light on how various peoples moved through the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire,” Ross said. “But this is the first study we know of in which anyone has used geometric morphometrics to evaluate imperial Roman remains.

“That’s important because geometric morphometrics offers several advantages,” she added. “It includes all geometric information in three-dimensional space rather than statistical space, it provides more biological information, and it allows for pictorial visualization rather than just lists of measurements.”

The study was published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.