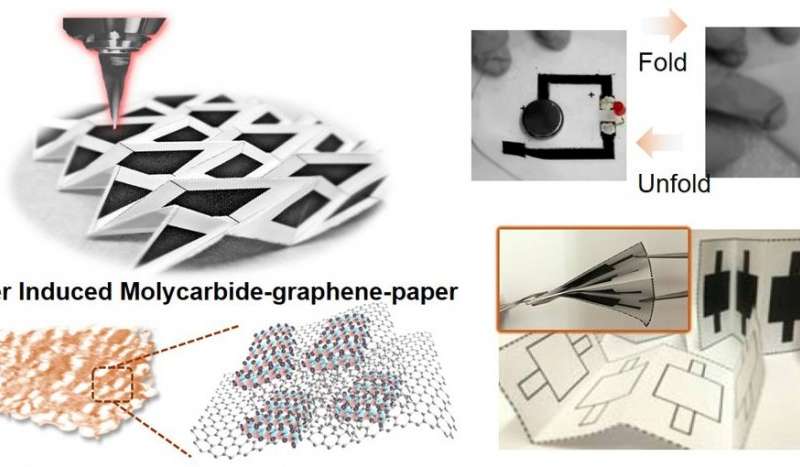

Berkeley engineers used a laser to “write” the circuitry for an electronic switch onto paper. They showed that folding and unfolding the paper could turn the circuit on and off. Credit: Xining Zang

Scientists have found a cheaper way to use foldable paper for electronic devices. Researchers from the University of California Berkeley have fabricated foldable electronic switches and sensors directly onto paper using inexpensive materials for use in generators, supercapacitors and other applications.

In recent years, researchers have sought to utilize paper for electronics due to its abundance and low cost, while also giving researchers the ability to switch circuits on and off or change their activity by simply folding the paper.

However, efforts to fabricate electrodes onto paper with sufficient conductivity for practical use has stalled, primarily because they generally require expensive metals like gold or silver as the conducting material.

The researchers replaced the more expensive metals with molybdenum, a cheaper source for the conducting metal.

The team added the molybdenum to gelatin in solution to bind with carbon. They then coated the paper with the solution and dried it.

The desired circuitry patterns, which are only about 100 microns wide, are written by a laser beam, ultimately heating the molybdenum to approximately 1,000 degrees centigrade and forming conductors of durable molybdenum carbide.

While the unheated portions of the paper are non-conductive, the gelatin coating provides the carbon for the conductive compound, while also preventing the laser beam from burning the paper.

“Without the gelatin, the paper would turn into ashes,” Liwei Lin, a professor of mechanical engineering and senior author of the paper, said in a statement.

The new technology opens the door for a number of new applications, including a circuitry written on paper that can detect heavy metal contamination to economically monitor toxins. A sensor could also be made of several electrodes that are integrated onto a paper circuit to detect unsafe lead levels in a drop of water or even a drop of a patient’s blood.

“The electrodes would have small gaps between them, and the presence of heavy metal in the sample would complete the circuit,” Xining Zang, PhD, who led the research as a Berkeley mechanical engineering graduate student in Lin’s lab, said in a statement.

The researchers developed the new strategy after experimenting with new types of switches, generators and batteries, along with studying the field of applying origami to electronic and mechanical applications.

“Many people have been carrying out origami research, forming different architectures and different shapes to perform different functions,” Lin said. “Our work provides a versatile and easy path to define conductive areas on the paper. We’ve now shown both the practicality of writing versatile conductive patterns on paper, and the durability of folding the electronic paper many hundreds of times for switching circuits on and off.”

Another potential use is for paper batteries, where a positive and negative electrode could be printed on paper that is folded to create the small gap needed between the electrodes.

The researchers also aim to integrate components for energy generation, storage and functional use— all on a single piece of paper.

“A self-contained, disposable sensor could be very useful in developing countries where portable, storable and inexpensive public health tools are in particular demand,” Zang said.

The study was published in Advanced Materials.