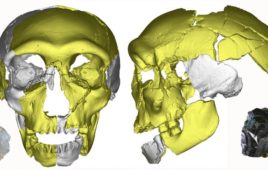

Heliconius butterfly (center) with a zoomed in image of wing scale color and pattern (left) and its corresponding stained wing pattern (right) with darker purple areas denoting where the optix gene is expressed prior to red pigmentation. |

Many tropical butterflies and moths have strikingly beautiful wing colors

and patterns. To scientists, though, studying these colors and patterns is less

about beauty and more about learning how some butterflies and moths have

managed to evolve deceptively similar or exceptionally diverse color patterns.

When butterflies mimic the wing patterns and colors of other butterflies who

successfully avoid predators, for instance, how does this work at a genetic

level? Is mimicry the result of a simple genetic switch turned on in each

species to yield similar wing patterns? Or is the genetic programming much more

complex than that?

In a paper published in Science, Heather Hines, a North Carolina State

post-doctoral genetics researcher, and collaborators show that an eye gene

called optix

appears to be responsible for the red patterns in tropical Heliconius

butterfly wings. The authors made the discovery by comparing the genes that are

turned on in butterflies with different color patterns. The somewhat surprising

proof of this single gene’s role came when—in a stage of development before

color was produced—the researchers stained wings wherever optix

occurred. They found the staining exactly matched the future distribution of

the red pigments—so well, in fact, that they could identify species by the

staining pattern alone.

“We finally found the gene switching these patterns on and off, but we also

determined that this gene is being used across a diversity of butterflies,

suggesting that a common genetic mechanism is employed across mimetic

butterflies to yield the same pattern,” Hines says.

Optix

is otherwise known only for its role in eye development, Hines adds, which adds

further intrigue to the study. Why would an eye gene be responsible for wing

colors or patterning? Hines and her colleagues have a guess: The red pigments

that optix

turns on are called ommochromes, pigments best known for their use as filtering

pigments in the eye. Production of optix outside its typical location could lead to the production of “eye”

pigments in the wing. Further, Heliconius

male butterflies prefer their own color pattern in mates, raising the

possibility that optix

could be programming both color pattern and visual mate preference.