New research has found that a crystal can be converted into an electrical circuit, paving the way for a bevy of new electronic devices.

Researchers at Washington State University have developed a method to write an electrical circuit into a crystal, which could result in transparent, 3D electronics that can be erased and reconfigured, similar to an Etch A Sketch.

The research team used a laser to etch a line in the crystal that carried a current, with electrical contacts at each end of the line.

“It opens up a new type of electronics where you can define a circuit optically and then erase it and define a new one,” Matt McCluskey, a WSU professor of physics and materials science, said in a statement. “It’s exciting that it’s reconfigurable.

“It’s also transparent. There are certain applications where it would be neat to have a circuit that is on a window or something like that, where it actually is invisible electronics,” he added.

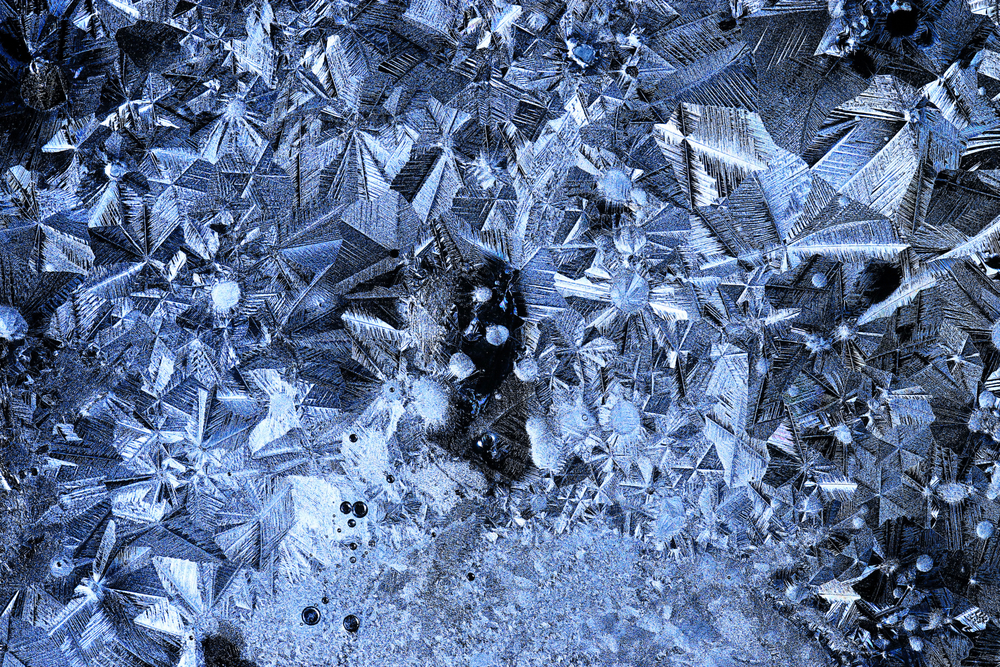

Crystals do not usually conduct electricity, but when the crystal strontium titanate is heated under the right conditions, it can be altered so light will make it conductive.

Persistent photoconductivity—a phenomenon where materials become much more conductive when light is shone on them—also occurs at room temperature, an improvement over materials that require cooling with liquid nitrogen.

“We’re still trying to figure out exactly what happens,” McCluskey said, adding that heat forces strontium atoms to leave the material, creating light-sensitive defects responsible for the persistent photoconductivity.

The work builds on previously research from 2013, when a doctoral student discovered a 400-fold increase in the electrical conductivity of a crystal by leaving it exposed to light.

In the new research, McCluskey was able to increase the crystal’s conductivity 1,000-fold for up to a year with the ability to be erased by heating it on a hot plate and recast with an optical pen.

“We look at samples that we exposed to light a year ago and they’re still conducting,” he said. “It may not retain 100 percent of its conductivity, but it’s pretty big.

“It’s an Etch A Sketch,” he added. “We’ve done it a few cycles. Another engineering challenge would be to do that thousands of times.”

The study was published in Scientific Reports.