Researchers have published the first part of what they expect to be a database showing the kinetics involved in producing colloidal metal nanocrystals — which are suitable for catalytic, biomedical, photonic, and electronic applications — through an autocatalytic mechanism.

In the solution-based process, precursor chemicals adsorb to nanocrystal seeds before being reduced to atoms that fuel growth of the nanocrystals. The kinetics data is based on painstaking systematic studies done to determine growth rates on different nanocrystal facets — surface structures that control how the crystals grow by attracting individual atoms.

In an article published Dec. 11 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a research team from the Georgia Institute of Technology provided a quantitative picture of how surface conditions controlled the growth of palladium nanocrystals. The work, which will later include information on nanocrystals made from other noble metals, is supported by the National Science Foundation.

“This is a fundamental study of how catalytic nanocrystals grow from tiny seeds, and a lot of people working in this field could benefit from the systematic, quantitative information we have developed,” says Younan Xia, professor and Brock Family Chair in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University. “We expect that this work will help researchers control the morphology of nanocrystals that are needed for many different applications.”

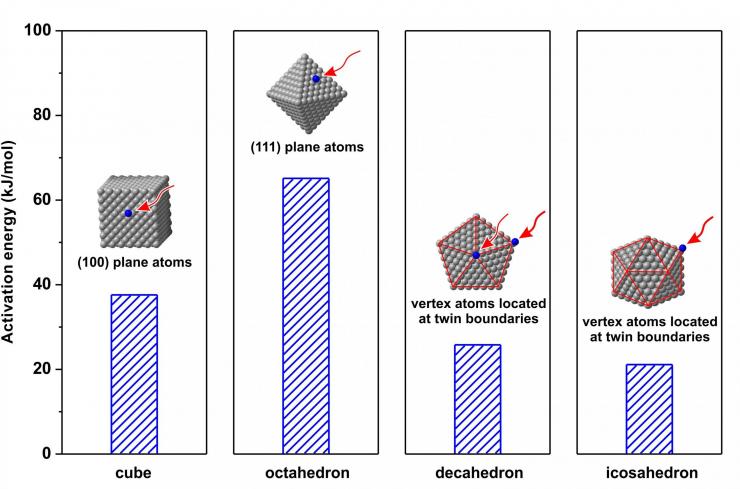

A critical factor controlling how nanocrystals grow from tiny seeds is the surface energy of the crystalline facets on the seeds. Researchers have known that energy barriers dictate the surface attraction for precursors in solution, but specific information on the energy barrier for each type of facet had not been readily available.

“Typically, the surface of the seeds that are used to grow these nanocrystals has not been homogenous,” explains Xia, who is also the Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar in Nanomedicine and holds joint appointments in School of Chemistry & Biochemistry and School of Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering. “You may have different facets on the crystals, which depend on the arrangement of the atoms below them. From the standpoint of precursors in the solution around the seeds, these surfaces have different activation energies which determine how difficult it will be for the precursors or atoms to land on each surface.”

Comparison of the activation energies involved in the autocatalytic surface reduction for the growth of palladium nanocrystals. Image: Xia laboratory, Georgia Tech

Xia’s research team designed experiments to assess the energy barriers on various facets, using seeds in a variety of sizes and surface configurations chosen to have only one type of facet. The researchers measured both the growth of the nanocrystals in solution and the change in concentration of palladium tetrabromide (PdBr4 2-) precursor salt.

“By choosing the right precursor, we can ensure that all the reduction we measure is on the surface and not in the solution,” he explains. “That allowed us to make meaningful measurements about the growth, which is controlled by the type of facet, as well as presence of a twin boundary, corresponding to distinctive growth patterns and end results.”

Over the course of nearly a year, visiting graduate research assistant Tung-Han Yang studied the nanocrystal growth using different types of seeds. Rather than allowing nanocrystal growth from self-nucleation, Xia’s team chose to study growth from seeds so they could control the initial conditions.

Controlling the shape of the nanocrystals is critical to applications in catalysis, photonics, electronics and medicine. Because these noble metals are expensive, minimizing the amount of material needed for catalytic applications helps control costs.

“When you do catalysis with these materials, you want to make sure the nanocrystals are as small as possible and that all of the atoms are exposed to the surface,” says Xia. “If they are not on the surface, they won’t contribute to the activity and therefore will be wasted.”

The ultimate goal of the research is a database that scientists can use to guide the growth of nanocrystals with specific sizes, shapes and catalytic activity. Beyond palladium, the researchers plan to publish the results of kinetic studies for gold, silver, platinum, rhodium, and other nanocrystals. While the pattern of energy barriers will likely be different for each, there will be similarities in how the energy barriers control growth, Xia said.

“It’s really how the atoms are arranged on the surface that determines the surface energy,” he explains. “Depending on the metals involved, the exact numbers will be different, but the ratios between the facet types should be more or less the same.”

Xia hopes that the work of his research team will lead to a better understanding of how the autocatalytic process works in the synthesis of these nanomaterials, and ultimately to broader applications.

“If you want to control the morphology and properties, you need this information so you can choose the right precursor and reducing agent,” says Xia. “This systematic study will lead to a database on these materials. This is just the beginning of what we plan to do.”

In addition to the researchers already mentioned, the study also included Shan Zhou, Kyle Gilroy, Legna Figueroa-Cosme, Yi-Hsien Lee, and Jenn-Ming Wu.

This work was supported in part by a research grant from the NSF (CHE 1505441) and startup funds from the Georgia Institute of Technology. The electron microscopy studies were performed at Georgia Tech’s Institute for Electronics and Nanotechnology, a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure supported by the NSF (ECCS-1542174).

Source: Georgia Tech