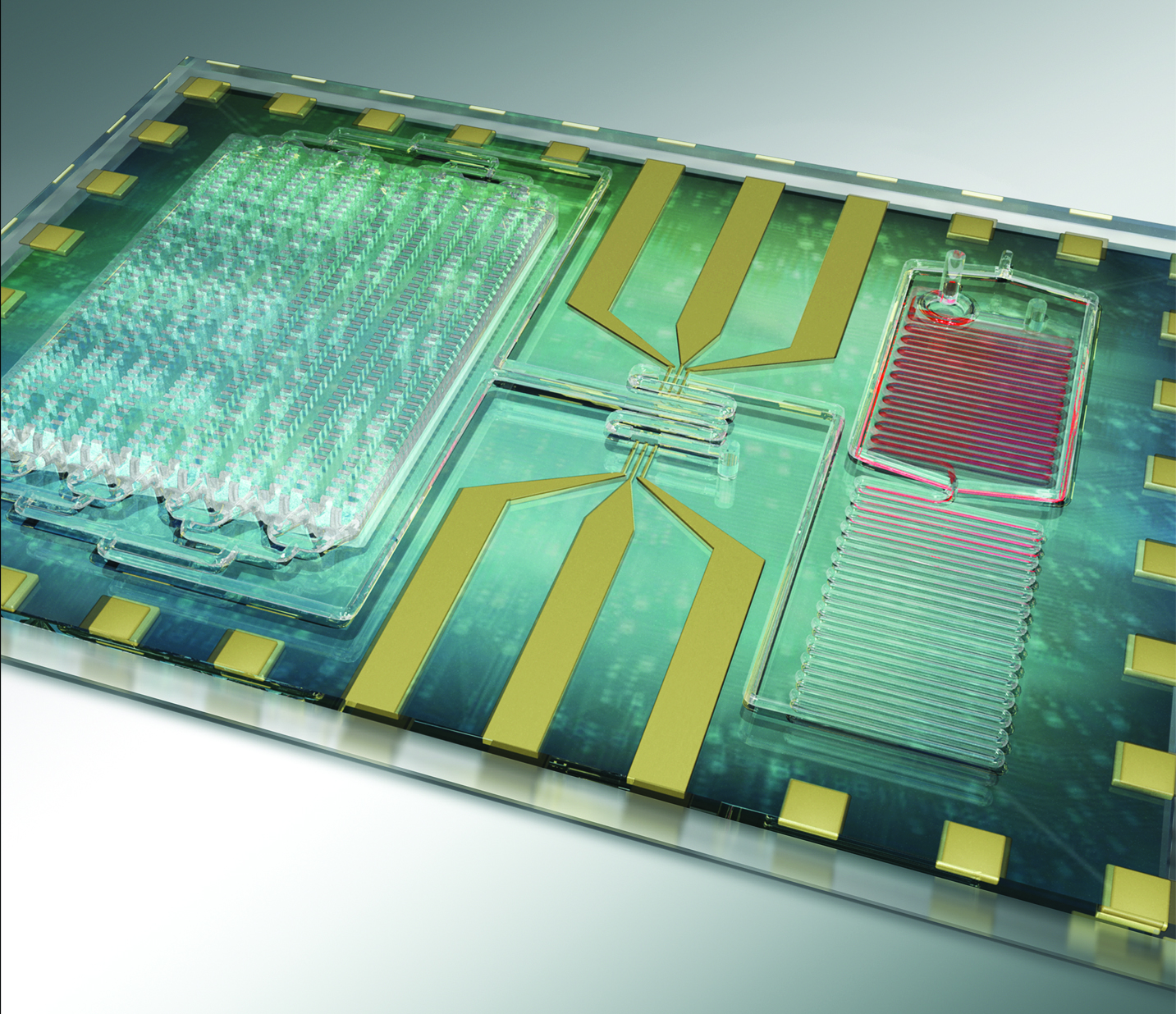

Sepsis biochip showing microfluidic channels that remove red blood cells on the right and the larger chamber of microchip posts on the left that capture the CD64 positive immune cells that are markers for sepsis. Image: Rashid Bashir, U. Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

NIH-funded biomedical engineers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have developed a rapid test using a single drop of blood for early detection of the deadly blood infection, sepsis. The microfluidic chip could enable early intervention for this life-threatening complication, which accounts for the most deaths and highest medical expenses in hospitals worldwide.

Sepsis is a particularly deadly illness caused by the body having an intense immune response to a bacterial infection. The cells and chemicals released by the immune system, instead of stopping the infection, overwhelm the body to cause blood clots, leaky blood vessels and, in severe cases, complete organ failure and death. Sick patients in hospitals are more susceptible because of their already weakened conditions.

Tiffani Lash, Ph.D., Director of the Point of Care Technologies Research Network (POCTRN), supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering at NIH explains, “Patients suspected of having sepsis have a much better clinical outcome when given antibiotics within the first hour. Therefore, the ability of this biochip to rapidly detect this pervasive and life-threatening condition is an outstanding example of the high impact point-of-care technologies envisioned when POCTRN was created.”

Lash further explained how the POCTRN network supports technology development through all phases including identifying an important clinical need, developing and testing the medical device, commercialization to get it into hospitals, clinics and other health care sites, and training health professionals to properly use the technology.

The work from researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign is reported in the July issue of Nature Communications.

Normally, sepsis is detected by monitoring patients’ vital signs such as temperature and blood pressure. If these vital signs are abnormal, blood cultures are done to try to identify the type and source of infection to attempt to treat the infection.

Team leader Rashid Bashir, Ph.D., Professor of Bioengineering and an Associate Dean at the Carle Illinois College of Medicine at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, explains that the chip is designed to speed up the diagnosis of sepsis with the goal of initiating treatment at the first signs of trouble.

“The time it takes to locate and start to treat the infection is what gets sepsis patients in trouble,” says Bashir. “Our strategy focuses on looking at the start of an immune response. The chip detects immune system factors mobilizing in the blood to fight the infection before the patent shows symptoms like a high fever. Our lab-on-a-chip device detects an increase in white blood cells and a surface marker called CD64 on the surface of a specific type of white blood cell called a neutrophil.”

The team developed the technology to detect CD64 because it is on the surface of the neutrophils that are known to surge in response to infection and cause the organ-damaging inflammation, which is the hallmark of sepsis.

The researchers tested the microchip with anonymous blood samples from patients in the Carle Illinois College of Medicine. Blood was drawn and analyzed with the chip when a patient appeared to be developing a fever. They continued to check the patients’ CD64 levels over time as the clinicians monitored the patients’ vital signs.

The group found that CD64 levels increasing or decreasing correlated with a patient’s vital signs getting worse or better, respectively. This first clinical use of the chip was a good indication that the rapid test for CD64 levels appears to be a promising approach for quickly identifying the patients who are most at risk for progressing into sepsis.

Bashir explained that the team is now working to incorporate several additional markers of inflammation into the rapid-test device. This would increase the accuracy of predicting whether a patient is likely to develop sepsis and aid in monitoring a patient’s response to treatment. Rapid monitoring of response would allow a patient to switch to a new drug faster if the inflammatory markers indicate the initial treatment is failing.

The work was supported through the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology (CIMIT)’s Point-of-Care Technology Center in Primary Care (POCTRN), which is a program funded by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. Additional funds were provided by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Source: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering