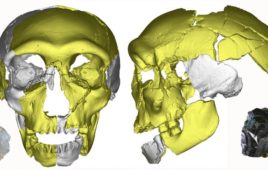

The Corythosaurus skull, collected in 1920 by George Sternberg, is in the University of Alberta’s Paleontology Museum. Credit: The University of Alberta

A Corythosaurus is now complete after being without its head for nearly a century.

Researchers at the University of Alberta matched a dinosaur skull—displayed at the university’s Paleontology Museum after being collected by George Sternberg in 1920— with its body— which has been displayed in Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta since the 1990s.

After examining newspaper clippings dating back to the 1920’s, scientists at the University of Alberta began to wonder if the skeleton at Dinosaur Provincial Park could be related to the skull at the University.

“Using anatomical measurements of the skull and the skeleton, we conducted a statistical analysis,” University of Alberta graduate student Katherine Bramble said in a statement. “Based on these results, we believed there was potential that the skull and this specimen belonged together.”

Researchers have found more new headless dinosaur skeletons recently, due to natural erosion and human activity digging up new specimens.

“In the early days of dinosaur hunting and exploration, explorers only took impressive and exciting specimens for their collections, such as skulls, tail spines and claws,” said Bramble. “Now, it’s common for paleontologists to come across specimens in the field without their skulls.”

“One institution will have one part of a skeleton. Years later, another will collect another part of a skeleton that could belong to the same animal,” she added.

According to Bramble, this particular aspect of paleontology has grown in recent years.

“Researchers are now trying to develop new ways of determining whether or not disparate parts of skeletons come from the same animal,” she said. “For this paper, we used anatomical measurements, but there are many other ways of matching, such as conducting a chemical analysis of the rock in which the specimens are found.”