A three-layered glove developed by materials chemist Trisha Andrew has one layer coated by the conducting polymer PEDOT and is powered by a button battery weighing 1.8 grams. Credit: UMass Amherst

The brutal cold days of winter may soon be easier with electrically heated clothing.

Researchers from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst have created a new vapor deposition method of nano-coating fabric that could result in sewable, weavable and electrically heated materials for gloves and other clothing.

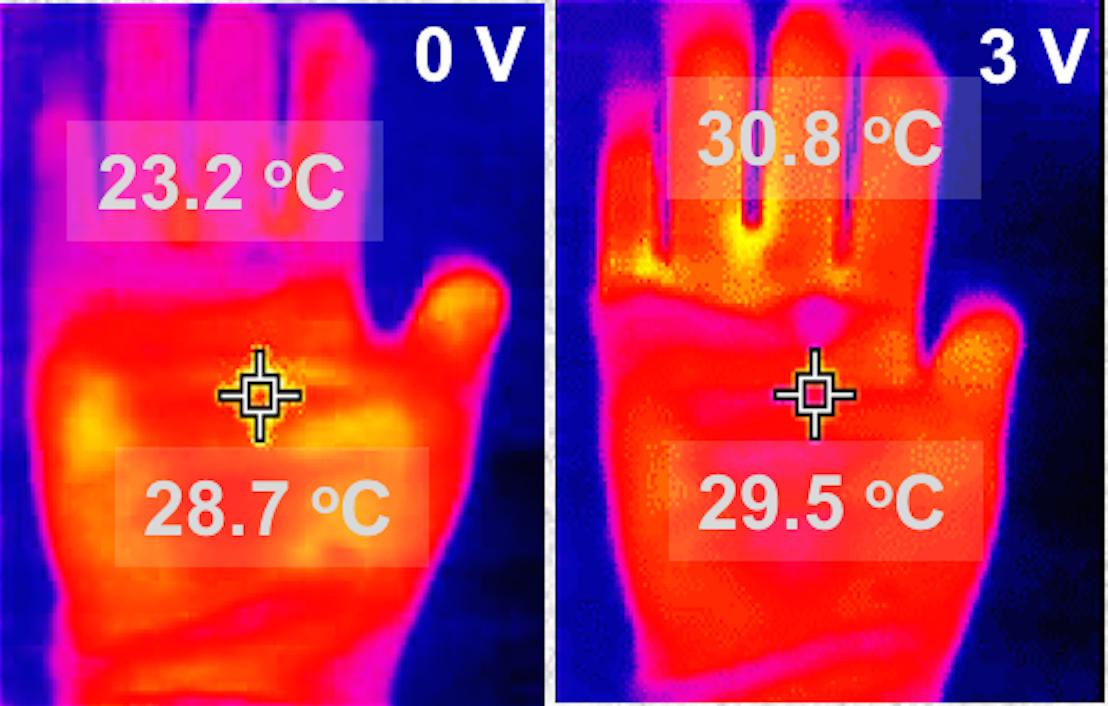

The researchers have demonstrated a glove that can keep fingers warm for up to eight hours by conducting polymer poly(3,4-ethylenedioxytiophene) or PEDOT powered by a button battery weighing 1.8 grams.

“We took a pair of cotton gloves and coated the fingers to allow a small amount of current to pass through, so they heat up,” UMASS materials scientist Trisha Andrew, said in a statement. “We chose to make a pair of gloves because the fingers require a high curvature that allows us to show that our material is really flexible.

“The glove is powered by a small coin battery and they run on nano-amps of current, not enough to pass current through your skin or to hurt you,” she added. “Our coating works even when it’s completely dunked in water, it will not shock you, and our layered construction means the conductive cloth does not come into contact with your skin.”

Vapor deposition has not been used previously by textile manufacturers due to technical difficulties and the high cost of scaling up from the laboratory. However, recently manufacturers are finding that the technology can be scaled up while remaining cost-effective.

“One thing that motivated us to make this product is that we could get the flexibility, the nice soft feel, while at the same time it’s heated but not making you sweaty,” Andrew said. “A common thing we hear from commuters is that in the winter, they would love to have warmer fingers.”

The researchers conducted several tests to assure that the gloves could stand up to hours of use, laundering, rips, repairs and overnight charging.

They also arranged for biocompatibility testing at an independent lab where mouse connective tissue cells were exposed to PEDOT-coated materials. They demonstrated that the gloves were safe to contact with human skin without causing adverse reactions to the chemicals used.

“Chemically, what we use to surround the conductive cloth looks like polystyrene, the stuff used to make packing peanuts,” Andrew said. “It completely surrounds the conducting material so the electrical conductor is never exposed.”

Andrew expects the product to reach consumers in the next five years with a prototype available in two years.