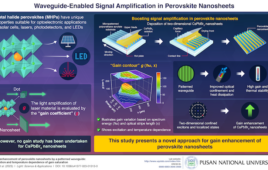

Illustration representing topography of a gold nanoring where a new method of sensing has been shown based on the damping of acoustic vibrations probed by transient absorption spectroscopy Copyright : A*STAR |

Metal

nanoparticles could play a key role in next-generation light detectors,

optical circuits, and cancer therapies. For these future technologies

to be realized, it is important to understand what happens when

nanoparticles are caused to undergo vibrations, and the consequent

scattering of light that can occur due to oscillations, or surface

plasmons, in their free electron cloud. However, little is known about

exactly how these vibrations are affected by the nanoparticle’s

immediate surroundings—in particular, how the environment affects the

dissipation of energy from a nanoparticle when it vibrates.

Sudhiranjan

Tripathy at the A*STAR Institute of Materials Research and Engineering

and co-workers, collaborating with Arnaud Arbouet and colleagues from

the National Center of Scientific Research (CNRS) in France, have now

analyzed the effect of different environments on individual gold

nanoparticles, their acoustic vibrations and associated energy

dissipation.

The

researchers examined individual nanorings made of gold using transient

absorption spectroscopy, which involves exciting the sample with a pulse

of laser light before measuring the absorbance of light at various

wavelengths. They measured both the vibration period and damping

time—the rate at which the nanoring loses its energy to its

surroundings.

“When

a metallic system is downsized to nanometric dimensions, its vibration

modes can become very different in comparison to its bulk form,”

explains Tripathy. “For example, the damping of the acoustic vibrations

is strongly affected by the elastic properties of the environment and

the interface between the nanoparticle and its environment.”

Previous

spectroscopy studies have experimented with large groups of

nanoparticles, but the collective approach has its limits because

nanoparticles of different sizes may have different vibration periods.

The researchers overcame the problem by working with individual

nanorings, but the workaround did have its own difficulties.

The

first challenge was the nanofabrication of perfectly controlled and

characterized nano-objects. Secondly, there was the issue of detecting

and monitoring the acoustic vibrations of one single metal nano-object.

This meant that the researchers had to measure relative changes on the

order of one in 10 million.

The

researchers studied individual nanorings that were surrounded by either

air or glycerol, and focused on how the different environments affected

the damping time of the vibrations. This provided valuable insight into

how energy dissipated from the nanorings to their environment. Most

tellingly, the damping times were significantly shorter in the highly

viscose glycerol.

“Our

work opens up exciting perspectives including the use of metal

nanoparticles as mass sensors, or as nanosized probes of the elastic

properties of their local environments,” says Tripathy.

Damping of the acoustic vibrations of individual gold nanoparticles