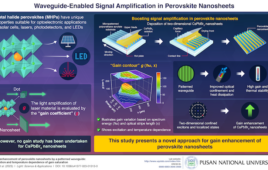

This microscopy image provided by Dr. Carl June on Wednesday, Aug. 10, 2011 shows immune system T-cells, center, binding to beads which cause the cells to divide. The beads, depicted in yellow, are later removed, leaving pure T-cells which are then ready for infusion to the cancer patients. Scientists are reporting the first clear success with gene therapy to treat leukemia, using the patients’ own blood cells to hunt down and wipe out their cancer. They’ve only done it in three patients so far, but the results were striking: two appear cancer-free up to a year after treatment, and the third had a partial response. Scientists are already preparing to try the approach in other kinds of cancer. (AP Photo/Dr. Carl June) |

NEW

YORK (AP) — Scientists are reporting the first clear success with a new

approach for treating leukemia — turning the patients’ own blood cells

into assassins that hunt and destroy their cancer cells.

They’ve

only done it in three patients so far, but the results were striking:

Two appear cancer-free up to a year after treatment, and the third

patient is improved but still has some cancer. Scientists are already

preparing to try the same gene therapy technique for other kinds of

cancer.

“It

worked great. We were surprised it worked as well as it did,” said Dr.

Carl June, a gene therapy expert at the University of Pennsylvania.

“We’re just a year out now. We need to find out how long these

remissions last.”

He led the study, published Wednesday by two journals, New England Journal of Medicine and Science Translational Medicine.

It

involved three men with very advanced cases of chronic lymphocytic

leukemia, or CLL. The only hope for a cure now is bone marrow or stem

cell transplants, which don’t always work and carry a high risk of

death.

Scientists

have been working for years to find ways to boost the immune system’s

ability to fight cancer. Earlier attempts at genetically modifying

bloodstream soldiers called T-cells have had limited success; the

modified cells didn’t reproduce well and quickly disappeared.

June

and his colleagues made changes to the technique, using a novel carrier

to deliver the new genes into the T-cells and a signaling mechanism

telling the cells to kill and multiply.

That

resulted in armies of “serial killer” cells that targeted cancer cells,

destroyed them, and went on to kill new cancer as it emerged. It was

known that T-cells attack viruses that way, but this is the first time

it’s been done against cancer, June said.

For

the experiment, blood was taken from each patient and T-cells removed.

After they were altered in a lab, millions of the cells were returned to

the patient in three infusions.

The

researchers described the experience of one 64-year-old patient in

detail. There was no change for two weeks, but then he became ill with

chills, nausea and fever. He and the other two patients were hit with a

condition that occurs when a large number of cancer cells die at the

same time — a sign that the gene therapy is working.

“It was like the worse flu of their life,” June said. “But after that, it’s over. They’re well.”

The

main complication seems to be that this technique also destroys some

other infection-fighting blood cells; so far the patients have been

getting monthly treatments for that.

Penn

researchers want to test the gene therapy technique in leukemia-related

cancers, as well as pancreatic and ovarian cancer, he said. Other

institutions are looking at prostate and brain cancer.

Dr.

Walter J. Urba of the Providence Cancer Center in Portland, Oregon,

called the findings “pretty remarkable” but added a note of caution

because of the size of the study.

“It’s

still just three patients. Three’s better than one, but it’s not 100,”

said Urba, one of the authors of an editorial on the research that

appears in the New England Journal.

What happens long-term is key, he said: “What’s it like a year from now, two years from now, for these patients.”

But

Dr. Kanti Rai, a blood cancer expert at New York’s Long Island Jewish

Medical Center, could hardly contain his enthusiasm, saying he usually

is more reserved in his comments on such reports.

“It’s an amazing, amazing kind of achievement,” said Rai, who had no role in the research.

One

of the patients, who did not want to be identified, wrote about his

illness, and released a statement through the university. The man,

himself a scientist, called himself “very lucky,” although he wrote that

he didn’t feel that way when he was first diagnosed 15 years ago at age

50.

He was successfully treated over the years with chemotherapy until standard drugs no longer worked.

Now,

almost a year since he entered the study, “I’m healthy and still in

remission. I know this may not be a permanent condition, but I decided

to declare victory and assume that I had won.”

Chimeric Antigen Receptor–Modified T Cells in Chronic Lymphoid Leukemia

SOURCE: The Associated Press