With graphene, Rutgers University researchers have discovered a powerful way to cool tiny chips — key components of electronic devices with billions of transistors apiece.

“You can fit graphene, a very thin, two-dimensional material that can be miniaturized, to cool a hot spot that creates heating problems in your chip, says Eva Y. Andrei, Board of Governors professor of physics in the Department of Physics and Astronomy. “This solution doesn’t have moving parts and it’s quite efficient for cooling.”

The shrinking of electronic components and the excessive heat generated by their increasing power has heightened the need for chip-cooling solutions, according to a Rutgers-led study published recently in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Using graphene combined with a boron nitride crystal substrate, the researchers demonstrated a more powerful and efficient cooling mechanism.

“We’ve achieved a power factor that is about two times higher than in previous thermoelectric coolers,” says Andrei, who works in the School of Arts and Sciences.

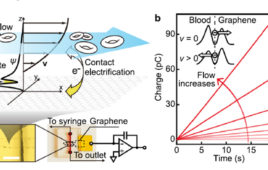

The power factor refers to the effectiveness of active cooling. That’s when an electrical current carries heat away, as shown in this study, while passive cooling is when heat diffuses naturally.

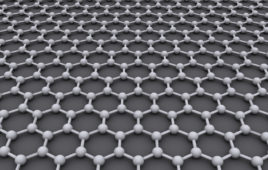

Graphene has major upsides. It’s a one-atom-thick layer of graphite, which is the flaky stuff inside a pencil. The thinnest flakes, graphene, consist of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb lattice that looks like chicken wire, Andrei says. It conducts electricity better than copper, is 100 times stronger than steel and quickly diffuses heat.

The graphene is placed on devices made of boron nitride, which is extremely flat and smooth as a skating rink, she says. Silicon dioxide — the traditional base for chips — hinders performance because it scatters electrons that can carry heat away.

In a tiny computer or smartphone chip, billions of transistors generate lots of heat, and that’s a big problem, Andrei says. High temperatures hamper the performance of transistors — electronic devices that control the flow of power and can amplify signals — so they need cooling.

Current methods include little fans in computers, but the fans are becoming less efficient and break down, she says. Water is also used for cooling, but that bulky method is complicated and prone to leaks that can fry computers.

“In a refrigerator, you have compression that does the cooling and you circulate a liquid,” Andrei says. “But this involves moving parts and one method of cooling without moving parts is called thermoelectric cooling.”

Think of thermoelectric cooling in terms of the water in a bathtub. If the tub has hot water and you turn on the cold water, it takes a long time for the cold water below the faucet to diffuse in the tub. This is passive cooling because molecules slowly diffuse in bathwater and become diluted, Andrei said. But if you use your hands to push the water from the cold end to the hot, the cooling process — also known as convection or active cooling — will be much faster.

The same process takes place in computer and smartphone chips, she says. You can connect a piece of wire, such as copper, to a hot chip and heat is carried away passively, just like in a bathtub.

Now imagine a piece of metal with hot and cold ends. The metal’s atoms and electrons zip around the hot end and are sluggish at the cold end, Andrei says. Her research team, in effect, applied voltage to the metal, sending a current from the hot end to the cold end. Similar to the case of active cooling in the bathtub example, the current spurred the electrons to carry away the heat much more efficiently than via passive cooling. Graphene is actually superior in both its passive and active cooling capability. The combination of the two makes graphene an excellent cooler.

“The electronics industry is moving towards this kind of cooling,” Andrei says. “There’s a very big research push to incorporate these kinds of coolers. There is a good chance that the graphene cooler is going to win out. Other materials out there are much more expensive, they’re not as thin and they don’t have such a high power factor.”

The study’s lead author is Junxi Duan, a Rutgers physics post-doctoral fellow. Other authors include Xiaoming Wang, a Rutgers mechanical engineering post-doctoral fellow; Xinyuan Lai, a Rutgers physics undergraduate student; Guohong Li, a Rutgers physics research associate; Kenji Watanabe and Takashi Taniguchi of the National Institute for Materials Science in Tsukuba, Japan; Mona Zebarjadi, a former Rutgers mechanical engineering professor who is now at the University of Virginia; and Andrei. Zebarjadi conducted a previous study on electronic cooling using thermoelectric devices.

Source: Rutgers University