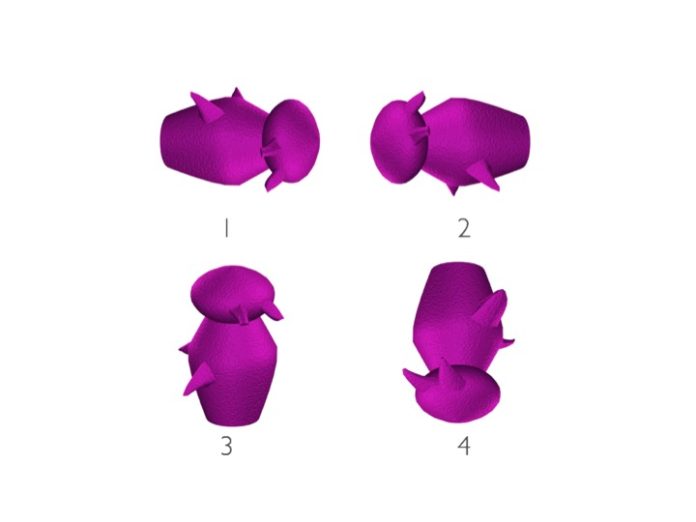

New research suggests that Alzheimer’s patients are less likely to be able to correctly identify the different Greeble (number 4) pictured here. Credit: The University of Louisville

Researchers are using unique graphic characters as the latest tool to help doctors detect signs of Alzheimer’s disease significantly earlier than when the symptoms become apparent.

Emily Mason, Ph.D., a postdoctoral associate in the Department of Neurological Surgery at the University of Louisville, led a study that shows that cognitively normal people who have a genetic predisposition for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have more difficulty distinguishing among novel figures called Greebles than individuals without genetic predisposition.

“Right now, by the time we can detect the disease, it would be very difficult to restore function because so much damage has been done to the brain,” Mason said in a statement. “We want to be able to look at really early, really subtle changes that are going on in the brain.”

Alzheimer’s is a progressive, irreversible neurodegenerative disease characterized by declining memory, cognition and behavior. It is considered the most prevalent form of dementia, affects an estimated 5.5 million individuals in the U.S., and accounts for 60 to80 percent of dementia cases.

The disease is characterized by the presence of beta amyloid plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles in the brain. The tangles develop first in the perirhinal and entorhinal cortices of the brain, which are areas that play a role in visual recognition and memory.

The researchers developed cognitive tests aimed at detecting subtle deficiencies in these cognitive functions, hoping to determine whether changes in these functions would indicate the presence of tau tangles before they could be detected through imagining or general cognitive testing.

Mason, while working at Vanderbilt University, identified test subjects between 40 and 60 years’ old who were considered at risk for Alzheimer’s due to having at least one biological parent diagnosed with the disease. Mason also tested a control group in the same age range whose immediate family history did not include the disease.

The subjects were shown sets of four images depicting real-world objects, human faces, scenes and Greebles in which one image was slightly different than the other three, and the subjects were asked to identify it.

The at-risk group scored lower in their ability to identify differences in the Greebles images, identifying the distinct Greeble 78 percent of the time while the control group was able to identify it 87 percent of the time.

“Most people have never seen a Greeble and Greebles are highly similar, so they are by far the toughest objects to differentiate,” Mason said. “What we found is that using this task, we were able to find a significant difference between the at-risk group and the control group.

“Both groups did get better with practice, but the at-risk group lagged behind the control group throughout the process,” she added.

According to Mason, the next step would be to follow through on the patients that performed poorly on the test to see if they actually developed Alzheimer’s in the future.

“The best thing we could do is have people take this test in their 40s and 50s, and track them for the next 10 or 20 years to see who eventually develops the disease and who doesn’t,” Mason said.