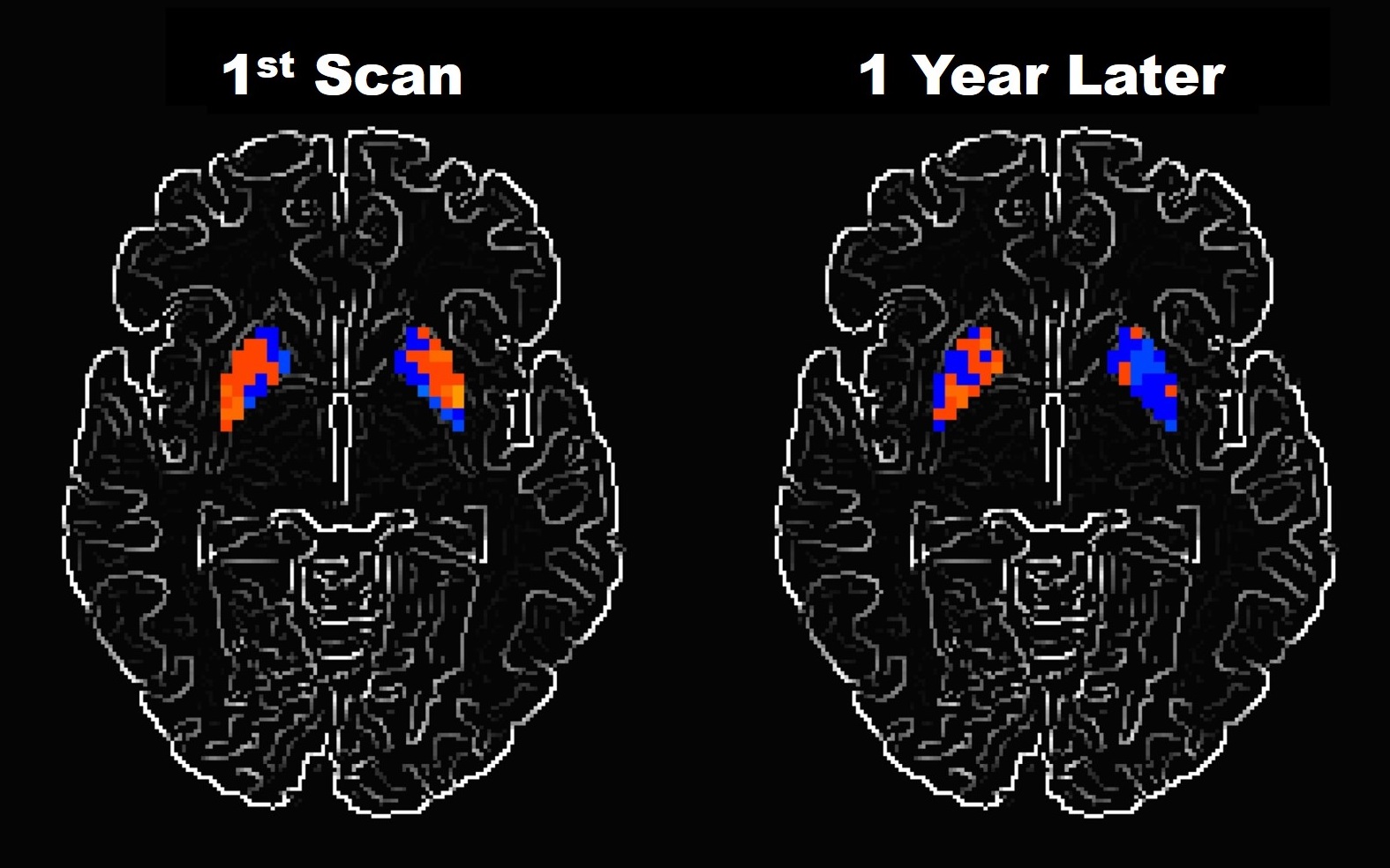

A new study has found that neural activity in certain brain areas declines over time in individuals with Parkinson’s disease and two related syndromes. Image courtesy of David Vaillancourt, Ph.D., University of Florida

Neuroscientists peered into the brains of patients with Parkinson’s disease and two similar conditions to see how their neural responses changed over time. The study, funded by the NIH’s Parkinson’s Disease Biomarkers Program and published inNeurology, may provide a new tool for testing experimental medications aimed at alleviating symptoms and slowing the rate at which the diseases damage the brain.

“If you know that in Parkinson’s disease the activity in a specific brain region is decreasing over the course of a year, it opens the door to evaluating a therapeutic to see if it can slow that reduction,” said senior author David Vaillancourt, Ph.D., a professor in the University of Florida’s Department of Applied Physiology and Kinesiology. “It provides a marker for evaluating how treatments alter the chronic changes in brain physiology caused by Parkinson’s.”

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that destroys neurons in the brain that are essential for controlling movement. While many medications exist that lessen the consequences of this neuronal loss, none can prevent the destruction of those cells. Clinical trials for Parkinson’s disease have long relied on observing whether a therapy improves patients’ symptoms, but such studies reveal little about how the treatment affects the underlying progressive neurodegeneration. As a result, while there are treatments that improve symptoms, they become less effective as the neurodegeneration advances. The new study could remedy this issue by providing researchers with measurable targets, called biomarkers, to assess whether a drug slows or even stops the progression of the disease in the brain.

“For decades, the field has been searching for an effective biomarker for Parkinson’s disease,” said Debra Babcock, M.D., Ph.D., program director at the NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). “This study is an example of how brain imaging biomarkers can be used to monitor the progression of Parkinson’s disease and other neurological disorders.”

“The Parkinson’s Disease Biomarkers Program is an essential part of moving towards the development of treatments that impact the causes, and not just the symptoms, of Parkinson’s disease,” added NINDS program director Katrina Gwinn, M.D.

Dr. Vaillancourt’s team used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure activity in a set of pre-determined brain areas in healthy controls, individuals with Parkinson’s disease, and patients with two forms of “atypical Parkinsonism” – multiple systems atrophy (MSA) and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) – that have symptoms similar to those of Parkinson’s disease. The researchers selected the specific brain regions, which are critical for movement and balance, based on the findings of past studies in people with these three conditions. The participants each underwent two scans spaced a year apart, during which they completed a test that gauged their grip strength.

The healthy controls showed no changes in neural activity after a year, whereas the participants with Parkinson’s showed reductions in the response of two brain regions called the putamen and the primary motor cortex. Previous research had shown reduced activity in the primary motor cortex of Parkinson’s patients, but the new study is the first to suggest that this deficit worsens over time. Activity decreased in MSA patients in the primary motor cortex, the supplementary motor area, and the superior cerebellum, while the individuals with PSP showed a decline in the response of these three areas and the putamen.

Dr. Vaillancourt’s team now hopes to use its newly discovered biomarkers, in addition to one it had previously identified, to test whether an experimental medication known to improve Parkinson’s symptoms also slows the progression of those brain changes.

“These markers allow us to evaluate disease-modifying therapeutics because we know that the control group doesn’t change over a year but patient groups do,” Dr. Vaillancourt explained. “We can see whether a therapeutic prevents that change from occurring, and if it does, then that suggests it might have a disease-modifying effect.”