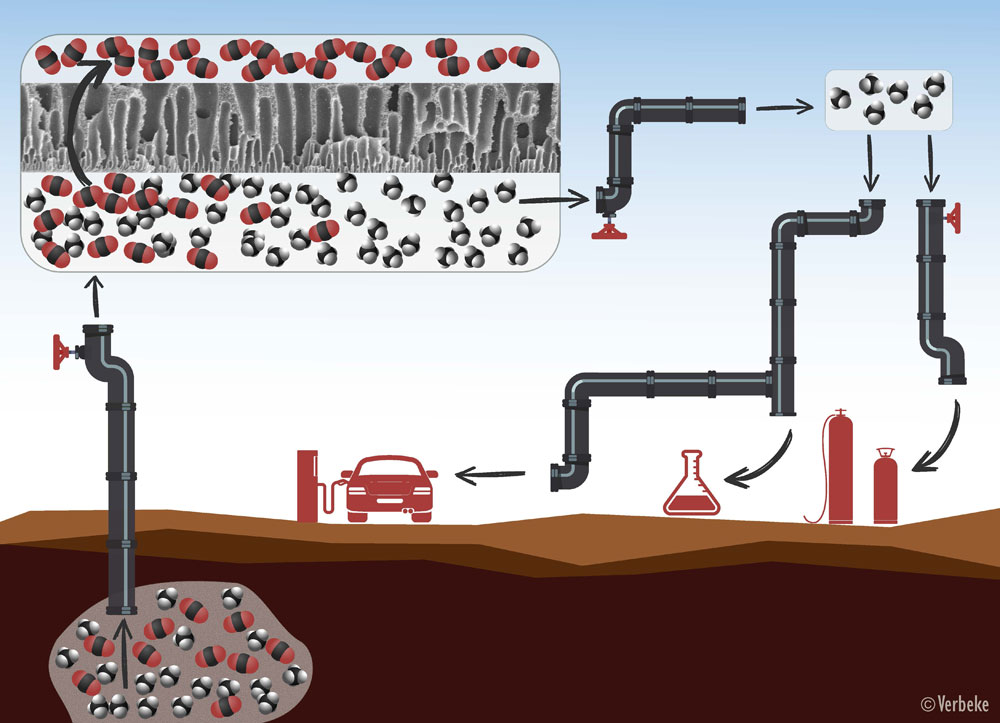

Natural gas or biogas always needs to be purified before use. First, the methane molecules (in black and white) are separated from the CO2 molecules (in red and black) by means of membranes with tiny pores through which only the CO2 can pass. After the purification process, the methane can be used as fuel, for heating, or for the production of chemicals.

When it comes to extracting natural gas or producing biogas, it’s all about the methane. But methane is never found in its pure form. Natural gas, for instance, always contains quite a bit of carbon dioxide (the greenhouse gas CO₂), sometimes up to 50 percent. To purify the methane — or, in other words, remove the CO₂ — the industry often uses membranes. These membranes function as molecular sieves that separate the methane and the CO₂. The methane can then be used as a source of energy for heating, for the production of chemicals, or as fuel, while the CO₂ can be reused as a building block for renewable fuels and chemicals.

Existing membranes still need to be improved for effective CO₂ separations, says Professor Ivo Vankelecom from the Faculty of Bioscience Engineering. “An effective membrane only allows the CO₂ to pass through, and as much of it as possible. Commercially available membranes come with a trade-off between selectivity and permeability: they are either highly selective or highly permeable. Another important problem is the fact that the membranes plasticize if the gas mixture contains too much CO₂. This makes them less efficient: almost everything can pass through them, so that the separation of methane and CO₂ fails.”

The best available membranes consist of a polymeric matrix with a filler in it, for instance a metal-organic framework (MOF). This MOF filler has nanoscale pores. The new study has shown that the characteristics of such a membrane improve significantly with a heat treatment above 160 degrees Celsius during the production process. “You get more crosslinks in the polymeric matrix: the net densifies, so to speak, and that in itself already improves the membrane performance, because it can no longer plasticize. At these temperatures, the structure of the MOF — the filler — changes, and it becomes more selective. Finally, the high-temperature treatment also improves polymer-filler adhesion: the gas mixture can no longer escape through little holes at the filler-polymer interface.”

This gives the new membrane the highest selectivity ever reported, while preventing plasticization when the concentration of CO₂ is high. “If you start off with a 50/50 CO2/methane mixture, this membrane gives you 164 times more CO₂ than methane after permeation through the membrane,” Dr. Lik Hong Wee explains. “These are the best results ever reported in scientific literature.”

Source: KU Leuven