There may be more large comets deep in space than previously believed.

A team of astronomers led by the University of Maryland has found that there are about seven times more large, ‘long-period’ comets than previously predicted. These are defined as comets that take more than 200 years to make a single revolution around the sun and are least one kilometer across.

The team also discovered that long-period comets are on average almost twice the size of Jupiter family comets—whose orbits are shaped by Jupiter’s gravity and have periods of less than 20 years.

“The number of comets speaks to the amount of material left over from the solar system’s formation,” James Bauer, a research professor of astronomy at the University of Maryland, said in a statement. “We now know that there are more relatively large chunks of ancient material coming from the Oort Cloud than we thought.”

Comets that travel inward from the Oort Cloud—a group of icy bodies beginning approximately 300 billion kilometers from the sun—can have periods of thousands or millions of years.

The distance makes it difficult to study, as the Oort Cloud is too far away to be seen by current telescopes. It is believed that the density of comets within the cloud is low, meaning the odds of the comets colliding with one another is low.

Using NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), the researchers observed that the long-period comets likely were kicked out of the Oort Cloud millions of years ago.

“Our study is a rare look at objects perturbed out of the Oort Cloud,” Amy Mainzer, a co-author of the study based at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California and principal investigator of the NEOWISE mission, said in a statement. “They are the most pristine examples of what the solar system was like when it formed.

“Comets travel much faster than asteroids and some of them are very big,” she added. “Studies like this will help us define what kind of hazard long-period comets may pose.”

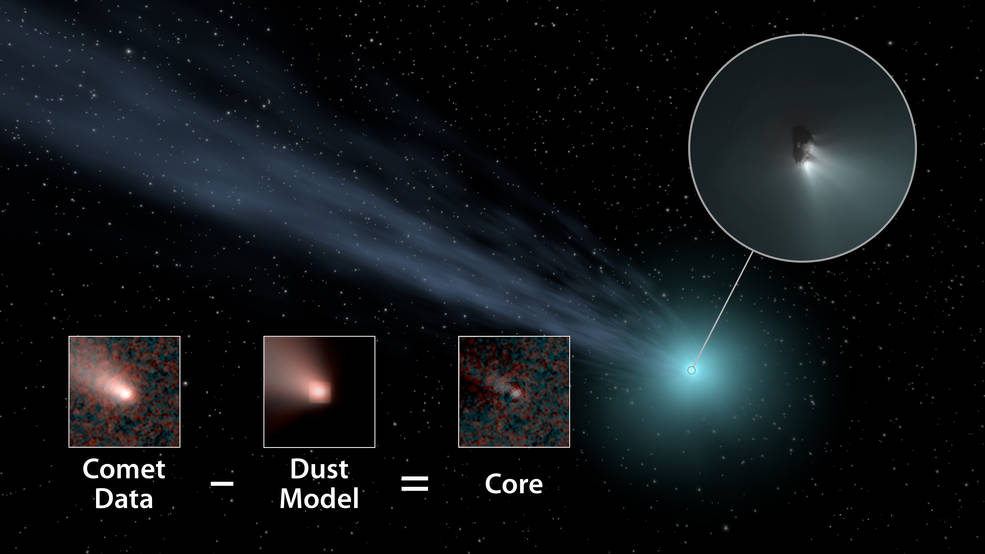

Astronomers previously had broader estimates of how many long-period and Jupiter family comets in the solar system there were, but were unable to measure the size of the long-period comets because the cloud of gas and dust that surrounds each comet appears hazy in images and obscures the comet’s nucleus.

The researchers used WISE data from 95 Jupiter family comets and 56 long-period comets to find the infrared glow of the coma and subtract the coma from each comet to estimate the size of the nucleus.

Comets that pass by the sun more frequently are likely smaller than those that are more distant because more heat exposure causes volatile substances like to water to sublimate and drag away other material from the comet’s surface.

With more long-period comets research estimate that more of them have impacted planets, delivering icy materials from the outer reaches of the solar system. Clustered orbits were also discovered among the long-period comets, suggesting there could have been larger bodies that broke apart to form the groups.