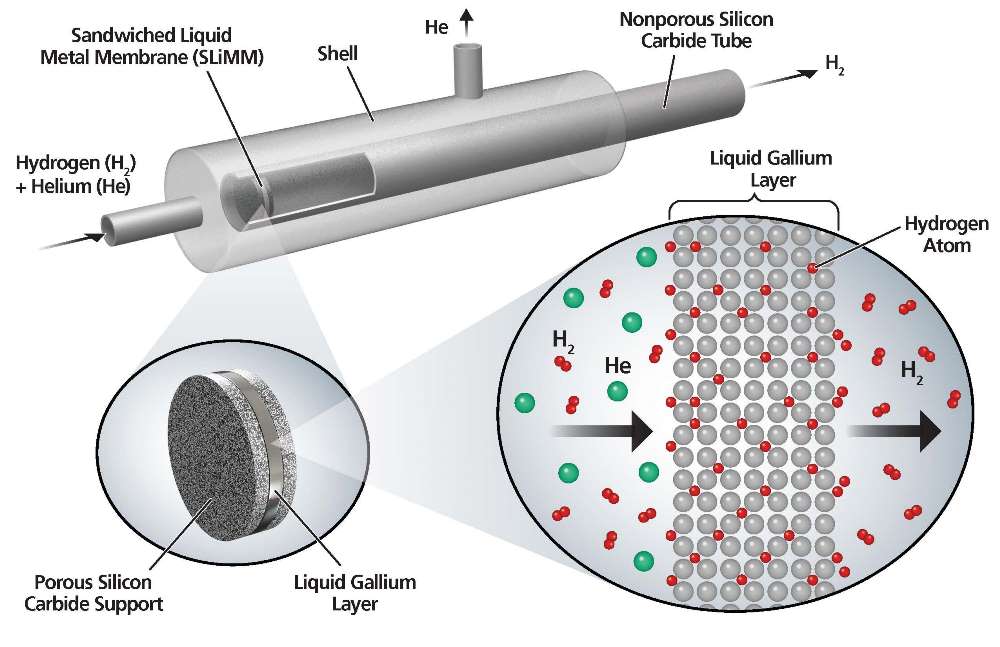

Ravi Datta and his team tested a prototype liquid metal membrane with this laboratory apparatus. The gallium layer exclusively allowed hydrogen to pass through. Credit: WPI

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles may be on the way, as researchers have discovered a more effective and cheaper way to produce hydrogen.

A team from Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) have replaced palladium— which is typically used to create hydrogen fuel cells—with liquid metals that can yield pure hydrogen. This could be used to create the new wave of energy efficient vehicles.

“We are still in the early stage but the application of this is in the distributed generation of hydrogen,” Ravindra Datta, a professor of chemical engineering at WPI, said in an interview with R&D Magazine. “Right now the hydrogen is produced in large plants that are complex and it is difficult to store and transport hydrogen because it is the lightest element.

“If you want to have fuel cell cars or you want to have hydrogen fuel cell filling stations you want to be able to produce hydrogen locally rather than transporting it over long distances,” he added. “You could conceivably have less complex and elaborate plants to produce fuel hydrogen.”

Cars powered by hydrogen fuel cells have a longer range with a lower overall environmental impact than electric cars and can be refueled in minutes.

However, it is currently expensive and complex to produce, distribute and store the pure hydrogen required to power them.

One of the main issues is that while hydrogen is the most abundant element in nature, it is almost always chemically bound to other elements, including with oxygen in water. Pure hydrogen must be separated from another molecule through a multi-step process in which the hydrocarbons react with high-temperature steam in the presence of a catalyst to produce carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and molecular hydrogen.

The hydrogen can then be separated from the other gases through a multi-step process that comes with a cumbersome chemical process and a high cost. Palladium is generally used to separate hydrogen from other gases. However, Palladium costs about $900 per ounce and the membranes are prone to cracking, which would render them useless.

“We’ve been looking for replacements and we’ve been looking at the mechanism of hydrogen separation by palladium,” Datta said. “Hydrogen actually dissociates on the surface into atoms and atoms diffuse through the interatomic space within the palladium membrane.

“So we thought if you could get liquid fill ins that perhaps you can increase the diffusion coefficient and the solubility of hydrogen atoms and therefore get a good permeation,” he added.

The host of liquid metals and alloys available are far less expensive than palladium and more effective at separating pure hydrogen from other gases.

Datta said the new process is less energy intensive.

He said the next step is to test the process on real gaseous mixtures including carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide.

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles have electric motors that are powered by electricity generated inside the fuel cell when hydrogen and oxygen combine in the presence of a catalyst.