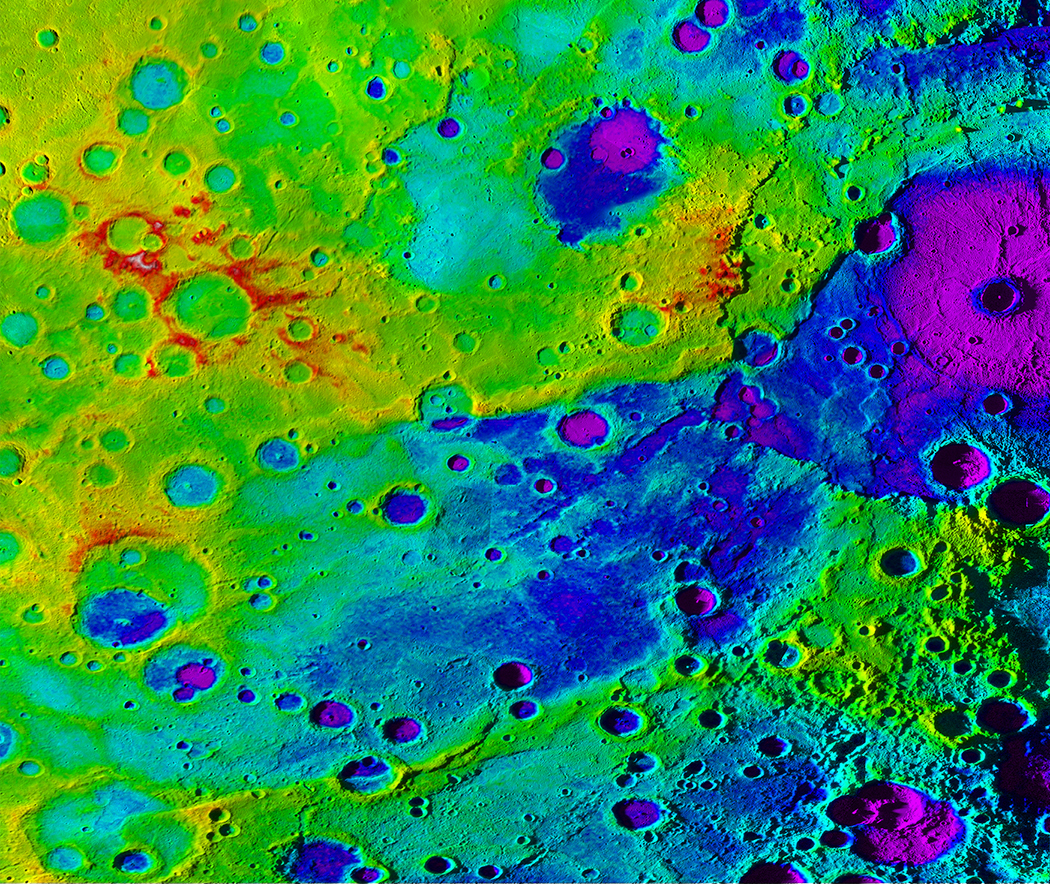

Using colorized topography, Mercury’s “great valley” (dark blue) and Rembrandt impact basin (purple, upper right) are revealed in this high-resolution digital elevation model merged with an image mosaic obtained by NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft. (Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/Carnegie Institution of Washington/DLR/Smithsonian Institution)

Scientists have discovered a valley on Mercury that could hold an important key to the geologic history of the planet.

The valley, located by scientists from the University of Maryland, the Smithsonian Institution, the German Institute of Planetary Research and Moscow State University, was discovered using stereo images from NASA’s MErcury Surface, Space Environment, GEochemsitry and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft.

The valley is located in Mercury’s southern hemisphere and would cover the area between New York City, Detroit and Washington, D.C., and is about twice as deep as the Grand Canyon.

In total, it is estimated to be about 250 miles wide and 600 miles long with steep sides that dip as much as 2 miles below the surrounding terrain.

Unlike Earth, Mercury has a single, solid lithosphere that covers the entire planet. However, Mercury’s lithosphere buckled and folded to form the valley as the planet cooled and shrank roughly 3 or 4 billion years ago.

“This is a huge valley,” Laurent Montesi, an assistant professor of geology at UMD and a co-author of the research paper, said in a statement. “There is no evidence of any geological formation on Earth that matches this scale.

“Mercury experienced a very different type of deformation than anything we have seen on Earth. This is the first evidence of large-scale buckling of a planet,” he added.

According to Montesi, the valley’s walls appear to be two large, parallel fault scarps—step-like structures where one side of a fault moved vertically with respect to the other.

The scarps plunge steeply to the flat valley floor, which could be because Mercury’s interior cooled rapidly, forming a strong, thick lithosphere.

The entire flood of the valley is a large piece of the lithosphere that dropped between the two faults on either side.

However, while most planets have been steadily cooling since their formation, Montesi said there are several clues that suggest Mercury went through a recent warming period.

“Most features on Mercury’s surface are truly ancient, but there is evidence for recent volcanism and an active magnetic field. This evidence implies that the planet is warm inside,” Montesi added. “Everyone thought Mercury was a very cold planet–myself included. But it looks like Mercury might have heated significantly in recent planetary history.”

The study, which appeared in Geophysical Research Letters on Nov. 16, can be viewed here.