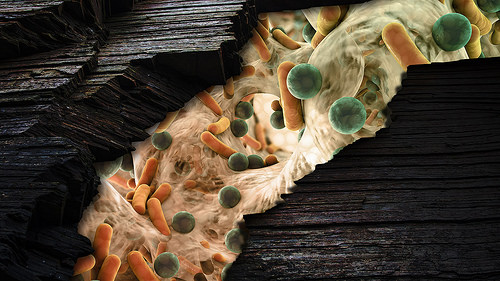

Illustration of microbes inside a fracking well. (Credit: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory)

As the battle over fracking rages on, at least one group of organisms has found a place to live down fracking wells.

Led by researchers at Ohio State University, scientists have discovered that microbes are supporting new microbial communities below ground by creating new compounds as a result of consuming some of the chemical ingredients commonly used in the fracking process. By doing this the microbes actually survive in very harsh environments that include very high temperatures, pressure and salinity.

The study, published in the October issue of Nature Microbiology, is based on samples from hydraulically fractured three Marcellus gas wells in Pennsylvania and one Utica well in Ohio over a 10-month period and despite the locations being different types of shales, more than 100 miles apart the microbes’ communities were similar.

Scientists studied microbes in fracking fluid more than a mile and a half below the ground surface and measured the metabolic byproducts excreted by the microbes, which can help identify what compounds the microbes are producing, where they are drawing energy from and what they need to stay alive. Over the course of the study, they identified 31 different microbes in fluids produced from hydraulic fracking shales.

The study will enable scientists to be able to better understand the complex interactions among microbes, which is important for understanding the plant’s environment and subsurface. The findings may also help scientists understand fracking wells and possibly offer insight into processes like corrosion.

David Hoyt, a biochemist within the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory (EMSL) at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, explained what is learned by examining the microbes dwellings down fracking wells.

“A thorough look at the metabolites of a community allows us to detect what chemical changes are occurring over time, how they support microbial life in the deep subsurface and what are the common biochemical strategies for these microbes that prevail across different shale formations,” Hoyt said in a statement.

Scientists observed several different compounds that were formed including—glycine betaine—which allows microbes to thrive against the high salinity found in the wells by degrading the compound to generate more food for the bacteria that produce methane.

Scientists also discovered a new strain of bacteria inside the wells being called “Frackibacter.”

Additional studies are now planned to understand the implications of the discovery, which go beyond fracking.

To do the study, researchers drew upon resources at two DOE Office of Science User Facilities. Resources at the Joint Genome Institute at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory helped researchers unravel the genetic sequences of microorganisms within the communities.