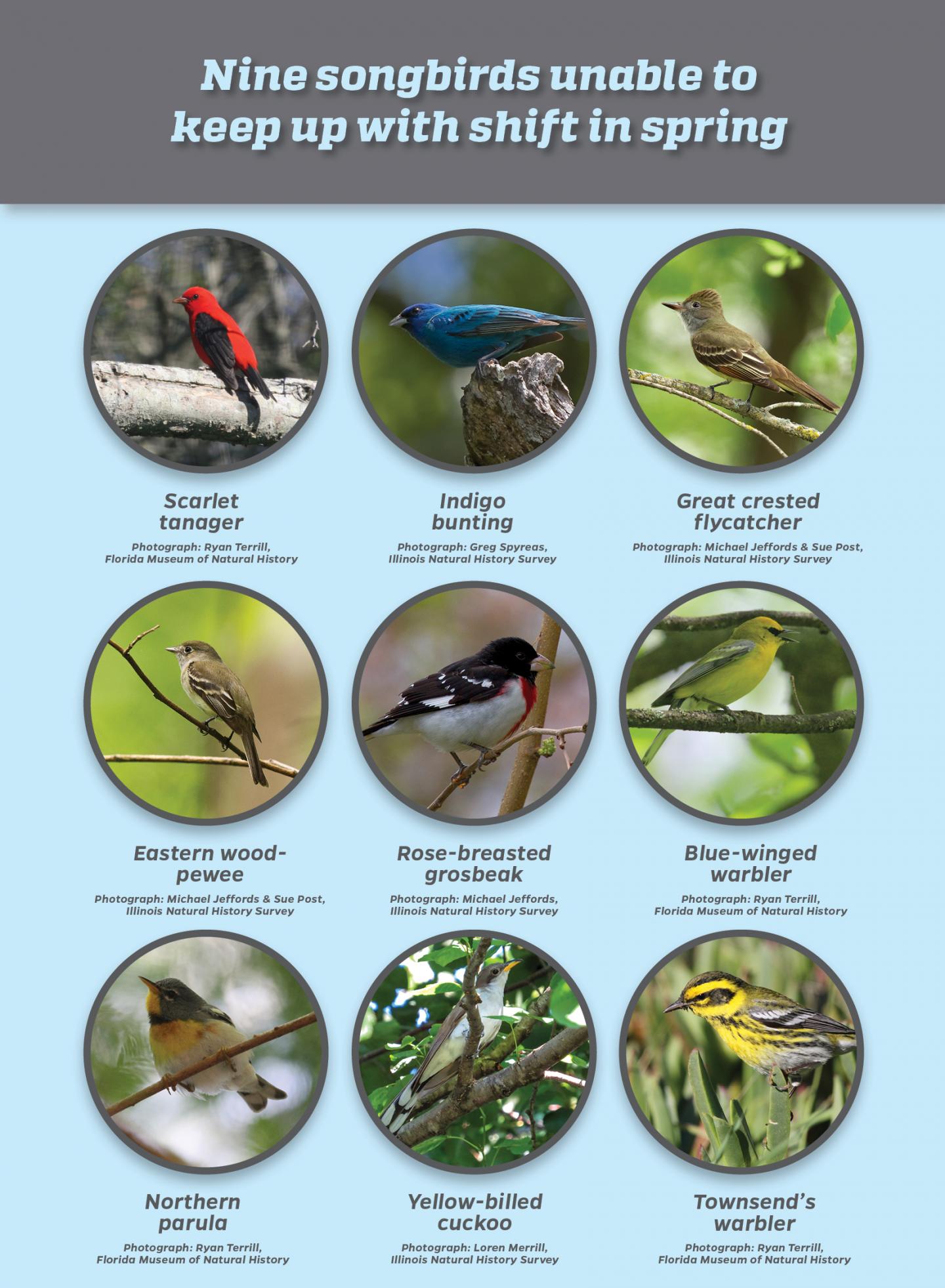

These nine species of migratory birds are not adjusting to spring’s shifting start date, possibly threatening their survival. CREDIT Elecia Crumpton, University of Florida

New research shows climate change is altering the delicate seasonal clock that North American migratory songbirds rely on to successfully mate and raise healthy offspring, setting in motion a domino effect that could threaten the survival of many familiar backyard bird species.

A growing shift in the onset of spring has left nine of 48 species of songbirds studied unable to reach their northern breeding grounds at the calendar marks critical for producing the next generation of fledglings, according to a paper published today in Scientific Reports.

That’s because in many regions, warming temperatures are triggering plants to begin their growth earlier or later than normal, skewing biological cycles that have long been in sync.

The result, researchers say, could be a future much like the one Rachel Carson hinted at more than 50 years ago.

“It’s like ‘Silent Spring,’ but with a more elusive culprit,” said Stephen Mayor, a postdoctoral researcher with the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida and first author of the study. “We’re seeing spring-like conditions well before birds arrive. The growing mismatch means fewer birds are likely to survive, reproduce and return the following year. These are birds people are used to seeing and hearing in their backyards. They’re part of the American landscape, part of our psyche. To imagine a future where they’re much less common would be a real loss.”

A multi-institutional team led by Mayor used data from satellites and citizen scientists to study how quickly the interval between spring plant growth and the arrival of 48 songbird species across North America changed from 2001 to 2012. The researchers found the gap lengthened by over half a day per year across all species on average, a rate of five days per decade–but for some species, the mismatch is growing at double or triple that rate.

Nine species were clearly unable to keep up with the shift: great crested flycatchers, indigo buntings, scarlet tanagers, rose-breasted grosbeaks, eastern wood-pewees, yellow-billed cuckoos, northern parulas, blue-winged warblers and Townsend’s warblers.

While the majority of species studied adjusted their arrival dates, the study suggests the rate of change could be outpacing their efforts.

The study is the first to investigate the increasing mismatch between songbirds’ springtime arrival and plant growth at the continental scale and across dozens of species, said Mayor, who led the project chiefly at Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Previous studies have predicted climate change will drive hundreds of bird species to extinction and greatly reduce the ranges of others. But some are shifting the timing of their major life events, such as reproduction and laying eggs, in an attempt to keep up with the changes.

The key question, Mayor said, is whether this strategy will work long term.

“If anything could adapt to climate change, you’d think that birds that migrate thousands of miles could,” he said. “It’s much easier for them to move in response to climate conditions than salamanders, for example, or trees. But because every species relates to another, one of our fears is that climate change can disrupt these relationships between organisms such that their critical life events are not timed optimally, putting them at risk.”

Birds leave their winter homes in Central and South America for the north based on the seasonal shift in hours of daylight, a cue unaltered by climate change. To produce healthy young, they must arrive at their breeding grounds to take advantage of the early-season boom in insects that emerge with springtime plant growth.

But as climate change shifts the timing of when plants put out new leaves — a temperature-driven process known as green-up – migrating birds become more likely to reach breeding grounds when temperatures are still frigid and food is scarce or after insect numbers have begun to dwindle.

The researchers found green-up is beginning earlier in eastern North America and — surprisingly — later in the West. Birds that breed primarily in eastern temperate forests tended to lag behind green-up while species that breed in western forests reached breeding grounds too early.

The rate of change is concerning, given predicted accelerating climatic changes, which could mean timing will be more out of sync in the future, said study co-author Rob Guralnick, associate curator of bioinformatics at the Florida Museum.

“That’s the future many of us will see,” he said. “Not every year will plot exactly along that line, but the trend is clear.”

The increased variability in weather conditions that comes with climate change could also compound birds’ difficulties in tracking year-to-year changes.

The team is examining why some species of birds seem to adjust to the shifts better than others, Mayor said.

A resource that enabled the study’s broad scale investigation of nearly 50 bird species across North America are the tens of thousands of data points contributed by citizen scientists, the researchers said.

“As more and more birders record their observations, they are creating a density of data that allows us to start from a continental level and zoom down further and further to the ground,” Guralnick said. “It’s powerful. Whether they know it or not, birders are helping scientists do their work, and they could end up helping birds in the process.”

The researchers emphasized the complexity of their findings, which vary by species, region and rate of change. Determining conservation risks and the potential for extinction will require looking at the impacts on each species individually, they said.

Diving deeper into the data to determine whether population numbers of bird species that are not adapting to the shift in green-up are falling is one of the next steps in the project.

“The natural world is very complex,” Mayor said. “When you kick it with a big change by altering the climate, different parts of that natural world respond in different ways. We’re just beginning to understand the consequences of this grand unnatural experiment.”