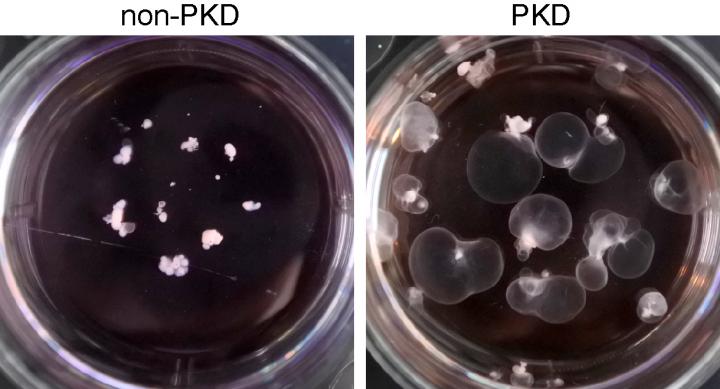

Kidney organoids grown in the lab and suspended in a lab dish show the formation of cysts (right) in the disease model of polycystic kidney disease. Normal kidney organoids are on the left. Source: Freedman Lab/UW Medicine

By creating and manipulating mini-kidney organoids that contain a realistic micro-anatomy, UW Medicine researchers can now track the early stages of polycystic kidney disease. The organoids are grown from human stem cells.

Polycystic kidney disease affects 12 million people. Until recently, scientists have been unable to recreate the progression of this human disease in a laboratory setting.

That scientific obstacle is being overcome. A report coming out next week shows that, by substituting certain physical components in the organoid environment, cyst formation can be increased or decreased.

Benjamin Freedman, assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Nephrology at the UW School of Medicine, and his team at the Kidney Research Institute, led these studies in conjunction with scientists at other institutions in the United States and Canada. Freedman and his group also are investigators at the UW Medicine Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine

They outlined their methods and results in a paper to be published Oct. 2 in Nature Materials

“Beforehand, we had shown that these organoids could form PKD-like cysts, but what’s new here is that we’ve used the model to understand something fundamental about that disease,” said Freedman.

As one example, the team found that PKD mini-kidneys grown in free-floating conditions formed hollow cysts that were very large. These cysts could easily be seen. In contrast, PKD mini-kidneys attached to plastic dishes stayed small.

According to Nelly Cruz, the lead author of the paper, other manipulations to the organoid also affect the progression of polycystic kidney disease.

“We’ve discovered that polycystin proteins, which are causing the disease, are sensitive to their micro-environment,” she explained. “Therefore, if we can change the way they interact or what they are experiencing on the outside of the cell, we might actually be able to change the course of the disease.” Cruz is a research scientist in the Freedman lab.

In another paper to be published in Stem Cells, Freedman and his team discuss how podocytes, which are specialized cells in the body that filter blood plasma to form urine, can be generated and tracked in a lab environment. Study of gene-edited human kidney organoids showed how podocytes form certain filtration barriers, called slit diaphragms, just as they do in the womb. This might give the team insight into how to counter the effects of congenital gene mutations that can cause glomerulosclerosis, another common cause of kidney failure.

Taken together, these papers are examples of how medical scientists are making progress toward developing effective, personalized therapies for polycystic kidney disease and other kidney disorders.

“We need to understand how PKD works,” Freedman said. “Otherwise, we have no hope of curing the disease.”

“And our research,” he added, “is telling us that looking at the outside environment of the kidney may be the key to curing the disease. This gives us a whole new interventional window.