Tympanic membrane (grey), ossicular chain (yellow, green, red), and bony inner ear (blue) of a modern human with a One-Eurocent coin for scale. Credit: A. Stoessel & P. Gunz

A team of researchers with members from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Jena University Hospital and University College London has taken a very close look at the middle ear structure of Neanderthals and has found that while there were some obvious differences, they appeared to be closer in structure to modern humans than apes. They have outlined their study and described their results in a paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

There has been a change in perception of Neanderthals in recent years as archaeologists have uncovered evidence that has suggested the extinct species of human was far more capable than has been conventionally believed. They built primitive homes, for example, created jewelry and painted on walls, and now, it appears they had an ear structure that would have enabled them to use vocal communications similar to modern humans. Prior research has suggested that Neanderthals came to exist approximately 280,000 years ago and lived in much of Europe and parts of Asia—but inexplicably disappeared approximately 40,000 years ago.

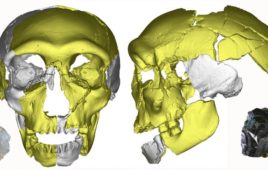

To learn more about the aural abilities of Neanderthals, the researchers gained access to ear bones from 14 Neanderthals that have been unearthed and then performed micro-CT scans on the ossicle (inner ear parts) to create 3-D digital models—this allowed the team to recreate the means by which the human sub-species would have responded to sound. In studying the models, the researchers discovered that there were obvious structural differences between Neanderthal and modern human inner ear workings, but they performed in functionally similar ways—more so than was seen in comparing ape inner ear workings with modern humans. This suggests that human and Neanderthal hearing got its start in our common ancestors

When combined with genetic research a decade ago that found the FOXP2 gene in Neanderthals associated with vocal communications and speech, these new findings suggest that Neanderthals were likely able to communicate with one another in ways that were far more advanced and sophisticated than apes or other animals. The researchers suggest that the differences in ear bone structure between modern humans and Neanderthals appears likely due to differences in brain size.