More than one in 10 babies worldwide are born prematurely, according to the World Health Organization. Now scientists report in ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering that they have developed an organ-on-a-chip that could help explain why. The device, which replicates the functions of a key membrane in the placenta, could lead to a better understanding of how bacterial infections can promote preterm delivery. It could also lead to new treatments for this condition.

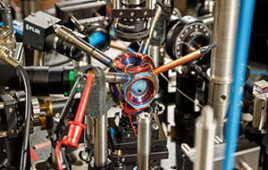

Bacterial infections, a common trigger of premature births, can cause inflammation of the placenta or the placental barrier, a membrane that regulates the flow of nutrients and other substances between mother and child. As a result, the amniotic sac can rupture, producing early-onset labor. Studying this problem has proven tricky, in part because it’s not feasible to run clinical trials including pregnant women, and human placentas donated after birth can only survive a few hours. However, researchers recently created a placenta-on-a chip — a promising new microfluidic device that allows placental cells to grow and function as if they were still in the body. Delving deeper, Jianhua Qin and colleagues sought to create a similar device that would specifically replicate the functions of placental barrier and how it responds to bacterial infection.

The researchers implanted human trophoblasts (representing the mother’s cells) and endothelial cells (representing the fetus) from a human umbilical cord vein onto opposite sides of a three-layer microfluidic device. A porous membrane between the two cell layers allowed the tissues to form a placental barrier between them. After determining that the barrier was functioning much as it would in the body, the researchers added E. coli bacteria to the maternal layer. The bacteria proliferated rapidly, breached the placental barrier, and subsequently triggered inflammation and cell death in both of the adjoining maternal and fetal layers. The researchers concluded that placental barriers-on-a-chip could help explain inflammatory responses in human placenta and possibly lead to better ways to treat or prevent preterm birth caused by infections.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Key Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the National Key R&D Program of China, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Innovation Program of Science and Research from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Source: American Chemical Society