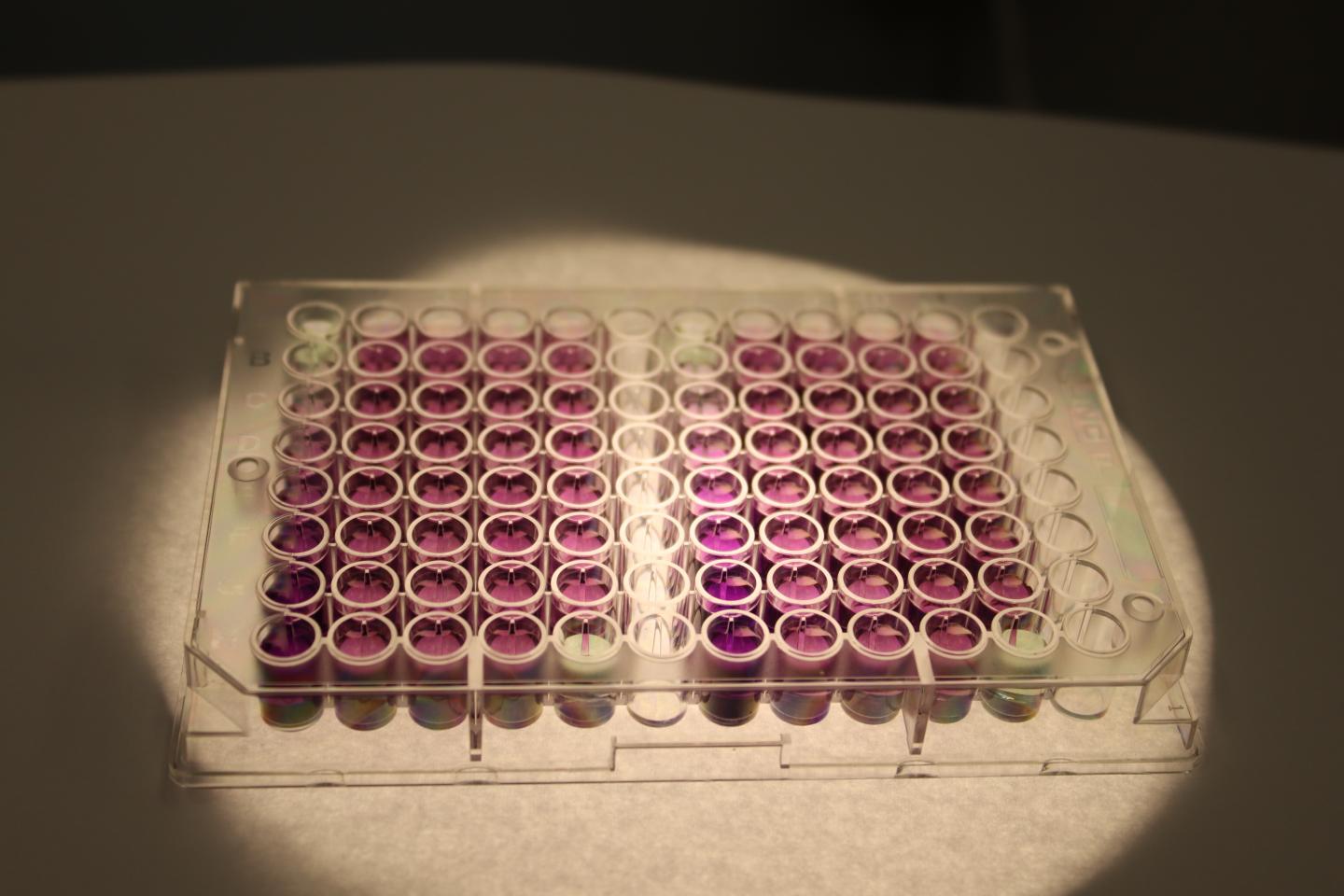

Soil protein is measured in the lab using a color-reading process called colorimetric analysis. Credit: Steve W. Culman

Scientists have found a novel way to measure nitrogen levels in soil, a discovery that could reduce nitrogen runoff—which can be damaging to the environment—and help farmers better determine nitrogen fertilizer needs.

Researchers from The Ohio State University and Cornell University have found that a test to measure a protein called glomalin in soil could be repurposed to measure several other proteins that will ultimately clue farmers into the nitrogen levels in soil.

Glomalin is produced by a common soil microorganism called arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, which has a beneficial relationship with plant roots.

“Here we propose a soil protein measurement as an indicator of a functionally relevant and sensitive pool of organic N that can be rapidly quantified in soil testing laboratories,” the study states. “The procedure is based on a method that was historically used to measure ‘glomalin,’ a pool putatively of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal origin.

“Laboratory validation experiments demonstrate that the procedure extracts proteins from a wide range of sources, not just glomalin, and that continued use of the term glomalin is inaccurate and limits the application of the method. Therefore, we propose that the pool of proteins extracted by this method can be viewed more broadly as a soil health indicator that reflects the primary pool of organically bound N in soil and thus as potentially available organic N.”

Previous studies found that the glomalin extraction method could extract proteins from other sources. The researchers tested the theory by adding a variety of sources of proteins including leaves from corns, beans and common weeds, chicken and beef and white button mushrooms and oyster mushrooms to soil samples.

After applying the glomalin protocol, the researchers found that proteins from all of the sources could be extracted, not just proteins produced by mycorrhizal fungi. The new test could prove to be a cost-effective, rapid method that could be readily adopted by commercial testing labs.

However, the researchers do warn that some specific protein types may not be recovered using this method.

“We don’t have many rapid ways to determine how much nitrogen a soil can provide and store over a growing season,” Steve Culman, an assistant professor and state specialist in soil fertility at Ohio State said in a statement. “This test is one way that might help us quickly measure an important pool of soil nitrogen.

“More work is needed to understand soil protein, but we think it has the potential to be used with other rapid measurements to assess the soil health of a farmer’s field,” he added.

Farmers usually send soil samples to the lab to test whether or not they are low in a number of key nutrients. However, most commercial tests do not measure the available nitrogen in soil and the tests that do measure nitrogen are often time-consuming and costly, forcing farmers to guess whether they need more or less nitrogen fertilizer.

Nitrogen fertilizer is often expensive and can lead to run-off that can cause problems in nearby bodies of water.

The study was published in Agricultural & Environmental Letters.