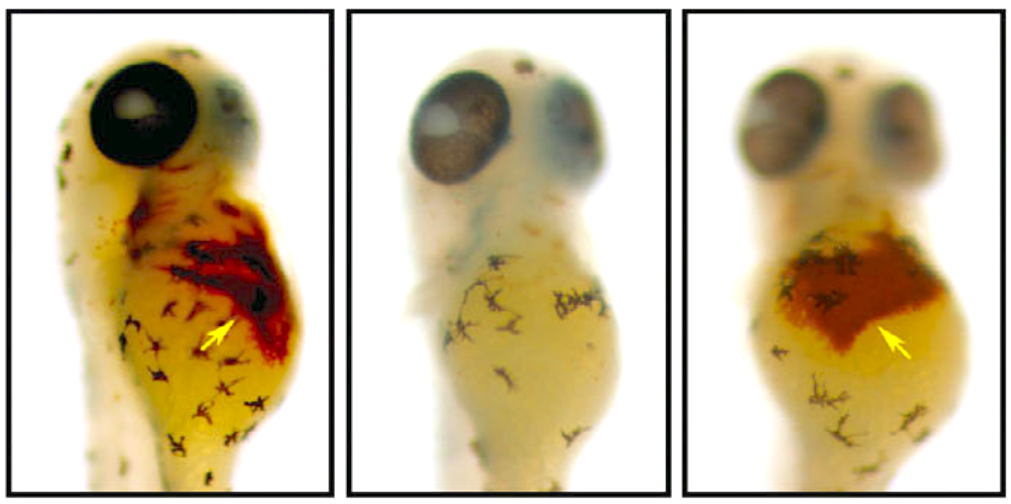

A special dye reveals hemoglobin production in a healthy zebrafish (left), an anemic zebrafish (middle) and an anemic zebrafish treated with hinokitiol (right). Credit: Boston Children’s Hospital

A new molecule could help researchers find a bevy of new therapy options to help treat patients with anemia and other iron disorders.

Researchers from several institutions including the University of Illinois, Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Northeastern University, have pinpointed hinokitiol—a small molecule found in Japanese cypress tree leaves could lead to treatments for a range of iron disorders including iron-deficiency anemia and iron-overload liver disease.

“Without iron, life itself wouldn’t be feasible,” Dr. Barry Paw, Ph.D., said in a statement. “Iron transport is very important because of the role it plays in oxygen transport in blood, key metabolic processes and DNA replication.”

The researchers successfully reversed iron deficiency and iron overload in zebrafish disease models using the molecule.

“Like most things in life, too much or too little of a good thing is bad for you; the body seeks homeostasis and balance,” Paw said. “Amazingly, we observed in zebrafish that hinokitiol can bind and transport iron inside or out of cell membranes to where it is needed most.”

The researchers discovered that the molecules can bind to iron atoms and move them across cell membranes and into and out of mitochondria, despite an absence of the native proteins that normally perform these functions.

“If there is a genetic error, cell membranes won’t open for iron to come across,” Paw said. “But when you administer hinokitiol, it combines with iron and ferries it into, within or out of the cells and mitochondria where iron is needed.

“Therefore, it’s a very interesting small molecule that has a lot of therapeutic potential,” he added.

They also found that hinokitiol could transport iron across cell membranes in vitro prior to testing it on animals.

Iron-related diseases are often hereditary or caused by an acquired loss of the protein function that is responsible for ferrying iron across cellular membranes subcellular compartments and mitochondrial membranes.

Iron is necessary for the body to produce hemoglobin—a protein that carries oxygen in the blood of vertebrates. However, when the proteins are missing, iron can’t get across cell membranes and inside the cells’ mitochondria, blocking a crucial step in hemoglobin production.

It is also problematic if too much iron builds up inside cells, causing tissue damage, DNA damage and life-threatening organ dysfunction across the heart, liver and pancreas. This is caused by a hereditary lack of iron-transporting proteins or from receiving frequent blood transfusions.

“If you’re sick because you have too much protein function, in many cases we can do something about it,” Dr. Martin Burke, Ph.D., the paper’s co-senior author, who led team members from the University of Illinois, said in a statement. “But if you’re sick because you’re missing a protein that does an essential function, we struggle to do anything other than treat the symptoms. It’s a huge unmet medical need.”