A new study has shed light on how humans migrated to South America.

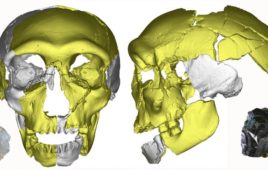

An analysis of ancient human skulls found in Brazil has researchers developing new theories of the complex narrative of human migration from sub-Saharan Africa to the Americas.

According to a study from the University of Buffalo, the many differences in cranial morphology seen in Paleoamerican remains found in the Lagoa Santa region of Brazil indicates a model of human history that included multiple waves of population dispersals from Asia, across the Bering Strait, down the North American coast and into South America.

The findings show that Paleoamericans share a last common ancestor with modern native South Americans outside, rather than inside, the Americas and underscore the importance of looking at both genetic and morphological evidence, each revealing different aspects of the human story.

“When you look at contemporary genomic data, the suggestion, particularly for South America, was for one wave of migration and that indigenous South American people are all descendants of that wave,” Noreen von Cramon-Taubadel, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Buffalo and the paper’s lead author, said in a statement. “But our data is suggesting that there were at least two, if not more, waves of people entering South America.”

While the debate over how people settled in the Americas rages on, this research suggests that the first human entry into the Americas began at least 15,000 years ago and dispersed quickly into South America following a coastal Pacific route.

However, there is still conflicting data between morphology and genetics, which is fueling the debate of how people first entered the New World. The new conclusions are similar to previous morphological research, while also relying on a pioneering method to reach these conclusions.

“We’ve adopted and modified the method from ecology, but to my knowledge this method has never been used in an anthropological setting before,” von Cramon-Taubadel said.

In previous studies, researchers have mainly looked at the overall similarities between the morphology of prehistoric skeletons from the Americas compared with the morphology of living people. Models of dispersal, each with a different number of waves that attempt to match existing data, have also been used.

However, von Cramon-Taubadel explained that all living people have a common ancestor but not all fossils necessarily contribute to the ancestry of living people. Some populations of modern humans did not survive or made only marginal contribution to living people, so fossils of these extinct humans provide very few clues about the ancestry of living people.

“There are other fossils, particularly in the Americas and Eurasia where at the moment we are not 100 percent sure how they fit into the human picture,” von Cramon-Taubadel said. “We could use this method to elucidate where they sit and to what extent those populations actually play a role in the modern ancestry of people in those areas.”

The study was published in Science Advances.