A series of laboratory tests were conducted on foresee using one of the “homes” in NREL’s Energy Systems Integration Facility. NREL researchers simulated how a house with a full complement of smart devices would run during a 24-hour span—first without the benefit of foresee’s automation or the storage battery to establish a baseline, and then with the software running based on user preferences.Image by Josh Bauer/NREL

With the amount of smart electronics and appliances on the market continuing to increase, personalizing all the connected equipment in a home can be a daunting task.

However, researchers from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) have developed new software dubbed “foresee” that relies on user preferences to automatically control and coordinate all the connected appliances and electronics in a home.

“Right now, if you had a smart dishwasher, a smart washer/dryer, and a smart water heater, you’d have to set up the schedule for everything yourself,” Bethany Sparn, a mechanical engineer and researcher at NREL, said in a statement. “You’d have to think about how the appliances interact with each other, the occupants, the building, and the power grid.

“Deciding when you should turn on your lights seems reasonably intuitive, but how should you control your water heater to reduce your utility bill and use solar energy from your solar panels, without risking your hot shower? Having automation that’s built in, that has an understanding of what’s required to keep people happy, is definitely not something that’s on the market now.”

To use the new software, the user must first rank what is important to them about living in their home, enabling the energy management system to take those preferences and automatically adjust all of the devices accordingly.

The majority of homeowners generally prioritize comfortable air temperature and hot water, convenience, reduced costs and a low environmental impact in their homes. However, determining the order of importance for those four categories is often difficult.

“These four categories are hard to trade off against each other,” Dane Christensen, leader of NREL’s Residential Systems Performance team and principal investigator on the foresee project, said in a statement. “At foresee’s core is a goal of running the home in a balanced way that best serves that family’s unique values and schedule.

“Your goals are going to be different from my family’s, just like a retiree on a fixed income is likely to have different goals than a millennial who just got her first job and is living large,” he added.

New technologies—like energy-efficient air conditioners and water heaters—have allowed homeowners to save on energy costs in recent years. However, the researchers believe additional savings can be achieved by coordinating when and how a home’s appliances operate—regardless of their efficiency.

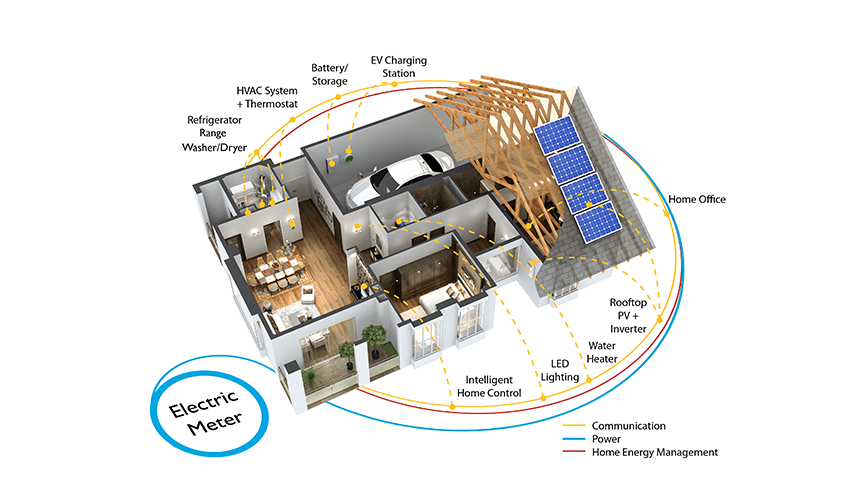

In testing, the researchers used various electronics and appliances including an air conditioner, refrigerator, dishwasher, washing machine, dryer, electric water heater and connected thermostat, a photovoltaic inverter and a battery that captures and stores electricity generated by the Sun.

The experiments used actual weather data to simulate a typical home in Denver.

“Every use case that we ran with foresee saved energy,” Sparn said. “Every use case we ran with foresee saved money. There’s definitely opportunity for improvement, but overall, the results were really good, really positive.”

They then tested the technology with simulations of Portland, Oregon where the weather is milder, Spokane, Washington where the weather swings from hot summers to cold winters, and Hawaii, with a tropical climate.

Each simulation resulted in a 5 to 40 percent energy savings, with most falling in the 10 to 15 percent range.

Foresee also accounts for time-of-use rates, a growing trend in the utility industry.

“Time-varying electricity costs can be confusing for homeowners to manage,” Christensen said. “Nobody wants to be sitting around making decisions for their appliances all the time. We’d really rather have it be automated and working for us in the background.”

According to Christensen, the software is currently available for licensing. He also said manufacturers could embed the technology in their products and a utility could run the software on a smart meter or in the cloud.

“This type of solution is a few years from being commercially available,” Christensen said. “Our next goal is to find field test sites where we can go out and do some pilot demonstrations. That will give us a whole lot of data to make the software even more effective—so it can become a product and be available for people to use.”

The team collaborated with Bosch and Colorado State University to build on previous research for preference-driven building automation.