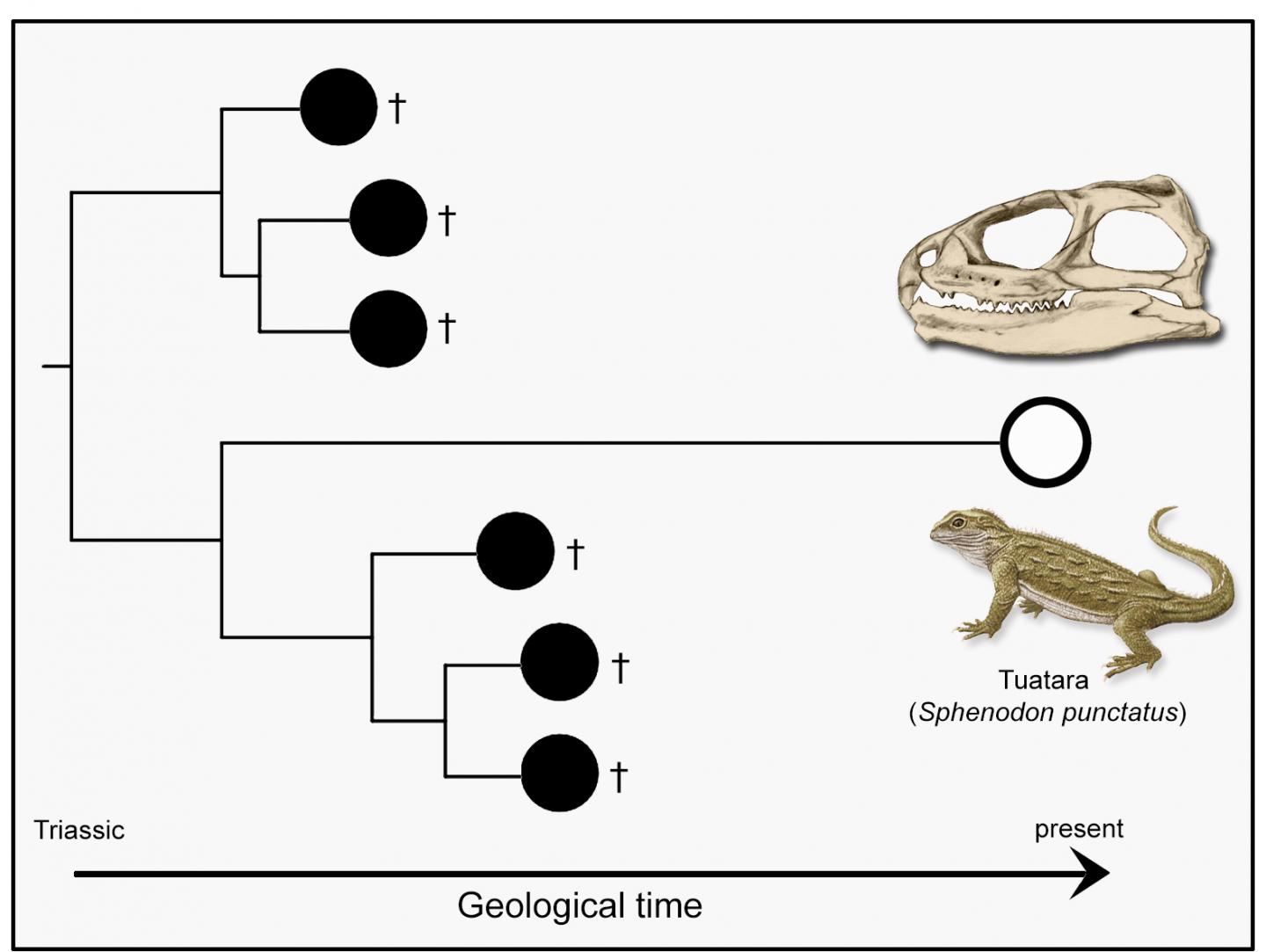

The living tuatara tracks back to the Triassic, over 200 million years ago, and shows little change from that time. Credit: Tom Stubbs/ University of Bristol

A new study has validated one of Charles Darwin’s longstanding theories about ‘living fossils.’

Darwin invented the term in 1859, after he observed living species that looked just like their ancestors of millions of years ago. These creatures occupied small parts of the world, escaped competition and therefore did not change.

A team of researchers from the University of Bristol have identified a new way to measure the evolutionary rate of the ‘living fossil’ Sphenodon punctatus or tuatara. The study confirmed that the tuatara has shown very slow evolution, as expected, and importantly, its anatomy is very conservative.

Tuatara is a relatively large lizard-like animal that once inhabited the main islands of New Zealand, but it was pushed to the 32 smaller, offshore islands by human activity.

While tuatara are not lizards, they share a common ancestor from about 240 million years ago and have survived as an independent evolutionary line since.

“Darwin’s wasn’t a testable definition,” Tom Stubbs, Ph.D., study co-author, said in a statement. “By using modern numerical methods we have now shown that living fossils should show unusually slow rates of evolution compared to relatives.”

The researchers measured the jaw bones from all fossil relatives of the living tuatara and compared these as evidence of dietary adaption. They also examined rates of morphological evolution in the living tuatara and its extinct fossil relatives.

Jorge Herrera-Flores, a Ph.D. student and lead author of the study, explained the research.

“The fossil relatives of the tuatara included plant eaters and even aquatic forms and were much more diverse than today,” Herrera-Flores said in a statement. “We found the living tuatara shares most in common with its oldest relatives from the Triassic.”

Mike Benton, professor of Vertebrate Palaeontology and head of School of Biological Sciences at the University of Bristol and co-author of the report, said the study confirms the existence of the living fossil.

“Many biologists do not like the term ‘living fossil’ because they say it is too vague,” Benton said in a statement. “However, we have presented a clear, computational way to measure evolutionary rate.

“More importantly, we discovered a second fact about the living tuatara: its adaptations are central among all its fossil relatives,” he added. “We can truly say that, numerically, the tuatara is conservative and just like its relatives from over 200 million years ago.

“We are with Darwin—we now have a numerical test of what is, and what is not, a living fossil,” Benton continued. “Importantly, these tests can be applied to other classic examples.”

According to the study, tuatara has often been noted as a classic living fossil because of its apparently close resemblance to its Mesozoic forebears and because of a long, low-diversity history.

“This designation has been disputed because of the wide diversity of Mesozoic forms and because of derived adaptations in living Sphenodon,” the study notes. “We provide a testable definition for ‘living fossils’ based on a slow rate of lineage evolution and a morphology close to the centroid of clade morphospace.”

Study was published in Palaeontology.