Despite advances in the field of volcanology, volcanoes are still unpredictable behemoths, capable of spurting forth magma and ash at a moment’s notice.

Despite advances in the field of volcanology, volcanoes are still unpredictable behemoths, capable of spurting forth magma and ash at a moment’s notice.

But scientists from the University of Oxford, Durham University, and the Vesuvius Volcano Observatory are attempting to understand what makes a volcano tick, or, more aptly, erupt. To do that, they’re looking to the past.

The Ancient Romans believed the Phlegraean Fields, a highly volcanic area located near Naples, was a mythological hotspot. A volcanic crater known as Solfatara was thought to be the home of Vulcan, the god of fire. Another crater — Lake Avernus — was believed to be the gateway to Hades.

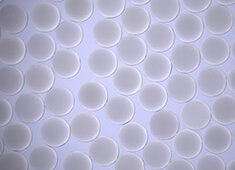

Studying ejecta expelled from the Phlegraean Fields’ caldera about 4,000 years ago, the scientists discovered that some eruptions are possibly triggered by a rapid proliferation of gas bubbles in magma chambers vey late in the volcanoes’ lifetime, and result in an eruption within days or months.

Previously, these buildups were believed to have occurred slowly over tens to hundreds of years.

The team’s research, which is published in Nature Geoscience, may point to a better indicator of an impending eruption. Instead of looking at the seismic activity and ground deformation, the researchers suggest monitoring the gases emitted at the Earth’s surface. A change in the gases may be the hallmark of an upcoming eruption.

In the study, the scientists looked to a mineral called apatite. “By looking at the composition of crystals trapped at different times during the evolution of the magma body — and with the apatite crystals in effect acting as ‘time capsules’ — the team was able to show that the magma that eventually erupted had spent most of its lifetime in a bubble-free state, becoming gas-saturated only very shortly before eruption,” according to the University of Oxford.

Prof. David Pyle, a coauthor of the study, explained that volcanologists are very much like physicians. Each volcano has a different set of traits, and a different history. Only by performing “the equivalent of a biopsy” can volcanologists truly understand what is occurring beneath the Earth’s surface.

With about 1,500 active volcanoes worldwide, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, scientists need to look into a lot more “patient histories” to truly make advances in volcanic eruption prediction.

“This still doesn’t provide us with a simple way to predict the eruptions of any volcano,” he writes in The Conversation. “But it does show how taking a forensic look at the deposits of past eruptions at a specific site offer a way to help identify the monitoring signals that will give us clues to future behavior. And this moves us a step closer to being able (to) predict when an eruption is likely.”