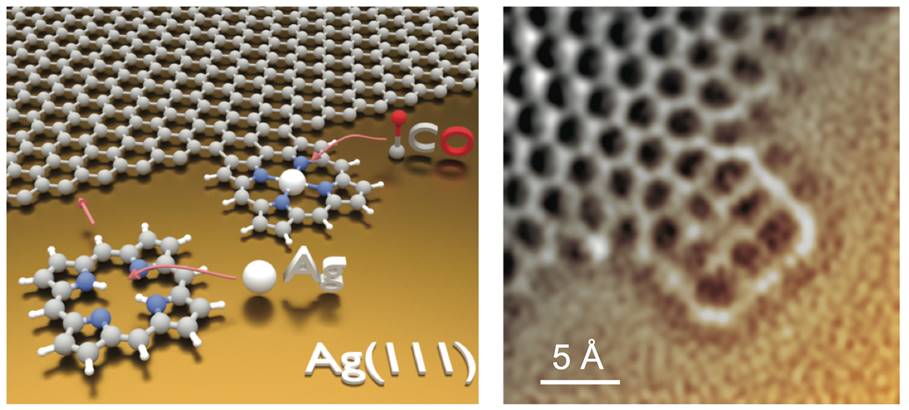

Credit: Willi Auwärter et al

Researchers from Technische Universität München in Germany have succeeded in covalently binding porphine to the edge of a graphene sheet on a Ag(111) substrate using surface-assisted covalent coupling. This provides a proof-of-principle that graphene edges can be functionalized with tetrapyrroles in a precise manner. Furthermore, their work shows that the graphene-porphine structure maintains its electronic and metal-binding properties. Their work appears in Nature Chemistry.

“Our findings open new perspectives for the controlled functionalization ofgraphene nanostructures and the embedding of porphines in graphene sheets,” comments Professor Willi Auwärter who co-authored this study. “We are excited by the potential of the resulting structures to catalyze distinct chemical reactions and anticipate applications in molecular electronics, sensing and optoelectronics.”

Tetrapyrroles, molecules that contain the heterocyclic five-member pyrrole ring, are key structures for several important biological molecules. Hemoglobin and chlorophyll, for example, are tetrapyrroles known as porphyrins. Porphyrins coordinate a metal in the center of the tetrapyrrole ring. Additionally, tetrapyrroles are stable molecules that can accommodate a variety of functional groups. Their delocalized electron framework, as well as their metal-binding properties, makes them an interesting study for molecular electronics.

In this study, porphine, the simplest tetrapyrrole, was covalently bound to a graphene edge. While prior studies by other groups have linked porphyrins to graphene sheets, they have done so using a more traditional chemistry route in which graphene oxide is reacted with the porphyrin in solution. This leads to a mixture of products and poor control over the porphyrin’s attachment points, which is not conducive to the precision necessary for molecular electronics.

He, et al. used surface-assisted coupling to covalently link porphine to graphene. They chose an Ag(111) substrate because of their experience with surface-assisted dehydrogenation reactions with porphines and because Ag(111) only weakly interacts with graphene.

According to the research paper, the goal was to use the surface both as a platform for graphene synthesis and to mediate the coupling reaction. The graphene edges needed to be clean and well-defined and the reaction with the porphine needed to be precise and controlled. The Ag(111) allows for this.

Once the graphene was grown on the Ag(111) surface, free-base porphines were vapor deposited at room temperature and then the surface was heated to over 620 K to induce the coupling reaction. Scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and non-contact atomic force microscopy (AFM) with a CO-functionalized tip showed that individual porphines appeared to be covalently linked to the graphene edges. Their studies showed that porphine bonding occurred in four configurations: 1) One C-C bond between the porphine and the graphene edge at the β position on the pyrrole; 2) two C-C bonds between the β pyrrole carbons and the graphene sheet; 3) three C-C bonds, one on a β pyrrole carbon, one bonded to the carbon between two of the pyrroles, and the other on a second β pyrrole position; 4) four C-C bonds with a similar pyrrole-carbon-pyrrole bonding structure as configuration 3, but with an additional C-C on one of the pyrroles.

After doping the substrate with CO, the STM images showed that some of the porphines had a protruding center that shows up as a bright spot. These protrusions were likely CO molecules attached to the metal center of the tetrapyrrole. This means that an Ag atom was coordinated to the tetrapyrrole center demonstrating that even when covalently bound to graphene, the porphine maintained its metal-coordination properties.

Additional tests showed that the conductivity of graphene at the edges where the porphines were attached did not change substantially. The thermal stability of the graphene-porphine structure was tested by gradually annealing the sample. The authors note that there was a 17% increase in the percentage of molecules bound to graphene after annealing the sample up to 770 K. Graphene is annealed to Ag(111) at 900 K. When the thermal stability test was taken to this temperature, He, et al. still observed prophines bound to the graphene edges, particularly porphines that have three and four carbons bonded to the graphene edge.

This study demonstrated a controlled and precise way to attach tetrapyrrole structures to graphene edges. This has important implications for further research in molecular electronics, sensors, and catalysis.