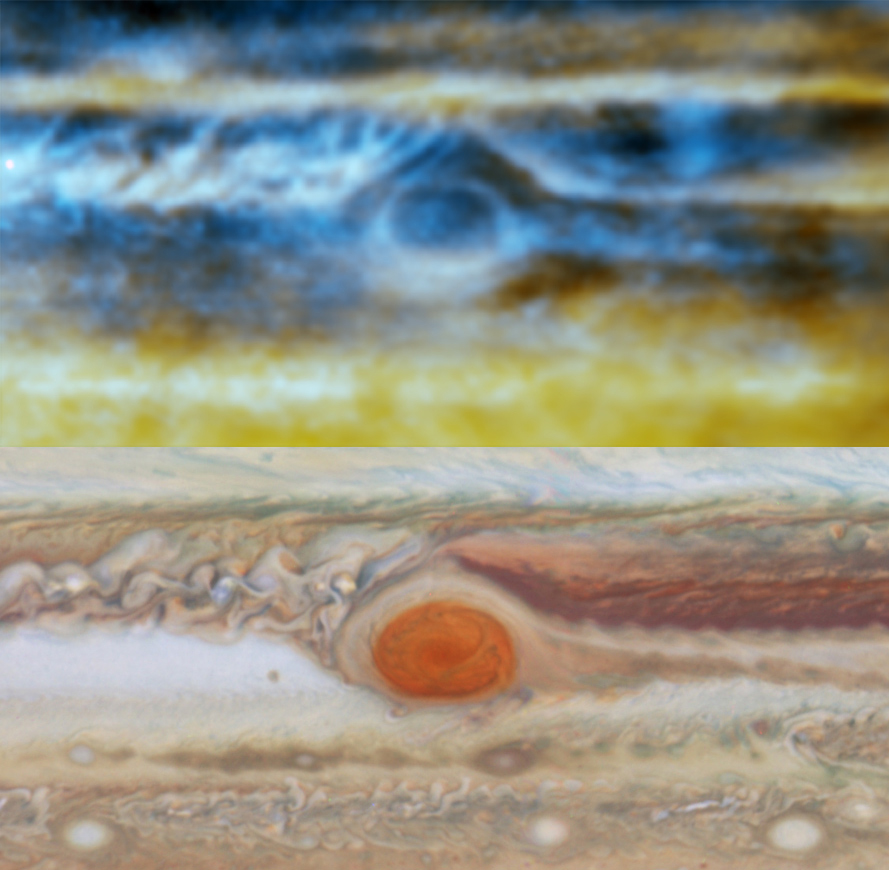

Optical image by NASA, ESA, A.A. Simon (GSFC), M.H. Wong (UC Berkeley), and G.S. Orton (JPL-Caltech)

Scientists have gotten under Jupiter’s colorful, cloudy, stripy exterior.

Using the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA), located in New Mexico, University of California, Berkeley researchers and colleagues have created the most detailed radio map of the gas giant, uncovering some of the processes occurring beneath the cloudy surface.

The maps have a spatial resolution of 1,300 kilometers.

In 1995, NASA’s Galileo spacecraft confirmed the notion that ammonia clouds exist on the planet. However, since then, scientists have wondered how prevalent the ammonia concentration was.

In the new study, which was published in Science, the researchers used radio emissions to peer as deep as 100 km beyond Jupiter’s cloud layer. Since the planet’s thermal radio emissions are absorbed by ammonia, the researchers were able to measure ammonia presence at certain depths.

“What really excited me is just the level of detail we see,” study author Michael Wong told BBC News. “In our maps you can see different zones, turbulent features, vortices—even the Great Red Spot … This has all been made possible by an upgrade to the VLA and a new technique developed by one of our co-workers.”

As explained by University of Melbourne’s Robert Sault, a co-author, the new technique diminishes the blur that occurs on radio maps due to Jupiter’s 10-hour rotation. “We have developed a technique to prevent this and so avoid confusing together the upwelling and downwelling ammonia flows,” Sault said in a statement.

Glancing at the radio map, the researchers saw the upper cloud layers formed from ammonia-rich gases. They saw two types of clouds, “an ammonium hydrosulfide cloud at a temperature near 200 Kelvin and an ammonia-ice cloud in the approximately 160 Kelvin cold air,” according to the University of California, Berkeley.

The radio map also revealed that ammonia-poor air sinks into the planet.

Bands of hotspots on the surface were also revealed to be ammonia-poor areas. “With radio, we can peer through the clouds and see that those hotspots are interleaved with plumes of ammonia rising from deep in the planet, tracing the vertical undulation of an equatorial wave system,” Wong said in a statement.

The find comes about a month before NASA’s Juno spacecraft will arrive at Jupiter. One of the spacecraft’s mission goals is to measure the amount of water in the planet’s atmosphere, among other atmospheric conditions.