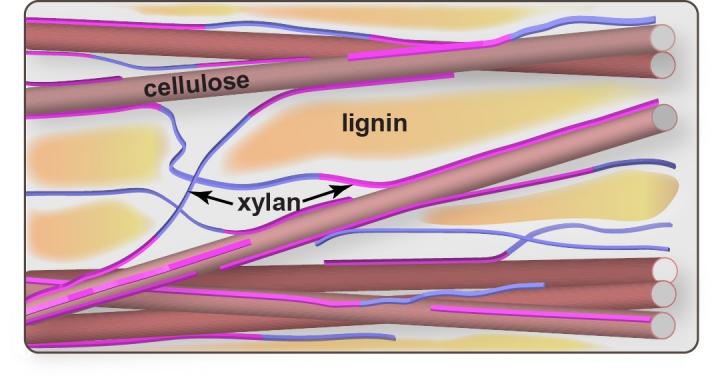

It has been previously thought that cellulose, a thick and rigid complex carbohydrate that acts like a scaffold in corn and other plants, connected directly to a waterproof polymer called lignin. However, Wang and colleagues discovered that lignin has limited contact with cellulose inside a plant. Instead, the wiry complex carbohydrate called xylan connects cellulose and lignin as the glue. Credit: Tuo Wang, LSU.

The inner structure of corn, one of the world’s most important crops, may be different than previously thought, a discovery that could lead to better biofuel production.

In the past, researchers believed that a thick and rigid complex carbohydrate called cellulose acts as a scaffold and connects directly to the lignin in corn. It was also thought that the cellulose, lignin and the molecules of a wiry complex carbohydrate called xylan molecules were all mixed together in the vegetable known for ethanol production.

However, a Louisiana State University (LSU) research team has taken an atomic level look at an intact corn plant stalk and found that the xylan connects directly to cellulose and lignin, meaning that the lignin and cellulose have very limited contact with each other. In fact, cellulose, lignin and xylan all have separate domains that perform three separate functions.

“I was surprised,” LSU Department of Chemistry Assistant Professor Tuo Wang, who led this study, said in a statement. “Our findings actually go against the textbook.”

While, scientists have sought new methods to break down plant structure or breed more digestible plants to produce biofuels like ethanol, they did not have a clear picture of the inner workings of the plant’s structure at the molecular level.

One of the challenges for ethanol conversion lies within the lignin, a waterproof polymer that prevents sugar from being converted to ethanol within plants.

While past studies using microscopes or chemical analysis prevented scientists from seeing the atomic-level structure of native, intact cell architecture, the LSU researchers are the first to directly measure the molecule structure of the intact plants.

To get the never before seen glimpse into the inner structure of corn, the researchers used a solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy instrument.

“A lot of work in ethanol production methods may need further optimization, but it opens doors for new opportunities to improve the way we process this valuable product,” Wang said.

With the new discovery, researchers can design a better enzyme or chemical to efficiently break down the core of corn and other plants and organism’s biomasses.

The research team also analyzed the structure of rice, switchgrass, which can also be used for biofuel production and Arabidopsis, a model flowering plant species that is related to cabbage and found that all three, as well as corn, had similar molecular structures.

The researchers are now using similar techniques to analyze wood from eucalyptus, poplar and spruce, which could lead to improved paper production and material development.

Corn is considered the most economically important plant in the U.S., with one-third of the nearly 15 billion bushels of corn produced annually in the U.S. used for ethanol production. Nearly all gasoline is comprised of 10 percent ethanol.

“Our economy relies on ethanol, so it’s fascinating that we haven’t had a full and more precise understanding of the molecular structure of corn until now,” Wang said. “Even if we can finally improve ethanol production efficiency by 1 or 2 percent, it could provide a significant benefit to society.”

The study was published in Nature Communications.