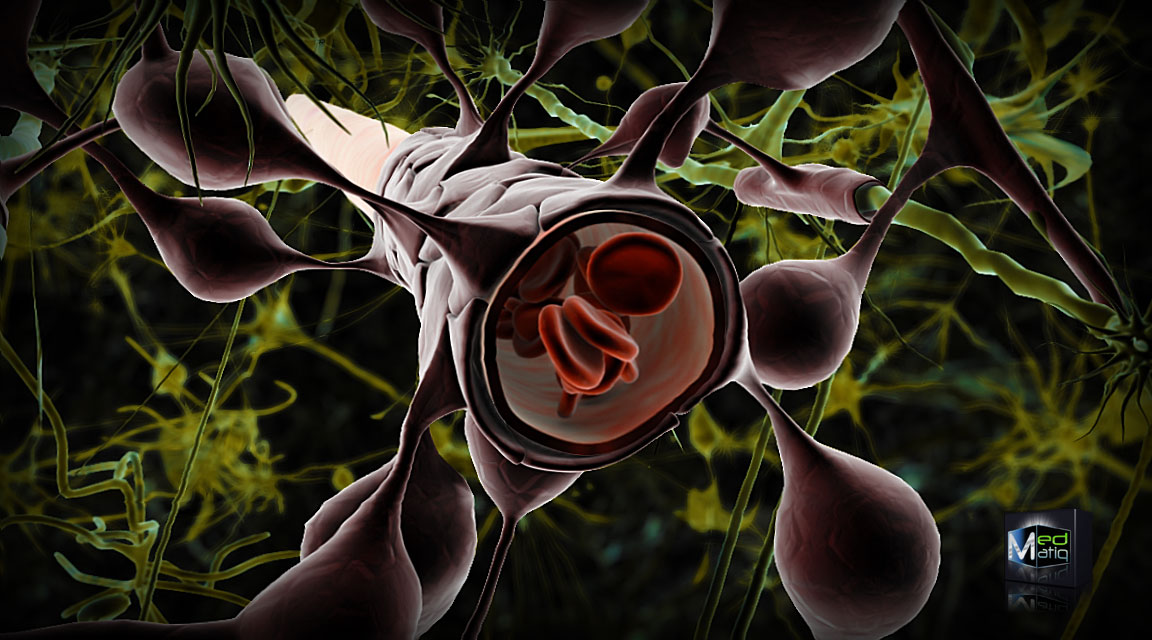

Illustration shows how the cells that make up the blood-brain barrier surround the blood vessels that run through the brain. This is the living structure that the new microfluidic device developed at Vanderbilt has succeeded in mimicking. Image: Ben Brahim Mohammed/Creative Commons License

The blood-brain barrier is a network of specialized cells that surrounds the arteries and veins within the brain. It forms a unique gateway that both provides brain cells with the nutrients they require and protects them from potentially harmful compounds.

An interdisciplinary team of researchers from the Vanderbilt Institute for Integrative Biosystems Research and Education (VIIBRE) headed by Gordon A. Cain University Professor John Wikswo report that they have developed a microfluidic device that overcomes the limitations of previous models of this key system and have used it to study brain inflammation, dubbed the “silent killer” because it doesn’t cause pain but contributes to neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Recent research also suggests that it may underlie a wider range of problems from impaired cognition to depression and even schizophrenia.

The project is part of a $70 million “Tissue Chip for Drug Testing Program” funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its purpose is to develop human organ-on-a-chip technology in order to assess the safety and efficacy of new drugs in a faster, cheaper, more effective and more reliable fashion.

The importance of understanding how the blood-brain barrier works has increased in recent years as medical researchers have found that this critical structure is implicated in a widening range of brain disorders, extending from stroke to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease to blunt force trauma and brain inflammation.

Despite its importance, scientists have had considerable difficulty creating faithful laboratory models of the complex biological system that protects the brain. Previous models have either been static and so have not reproduced critical blood flow effects or they have not supported all the cell types found in human blood-brain barriers.

The new device, which the researchers call a NeuroVascular Unit (NVU) on a chip, overcomes these problems. It consists of a small cavity that is one-fifth of an inch long, one-tenth of an inch wide and three-hundredths of an inch thick — giving it a total volume of about one-millionth of a human brain. The cavity is divided by a thin, porous membrane into an upper chamber that acts as the brain side of the barrier and a lower chamber that acts as the blood or vascular side. Both chambers are connected to separate microchannels hooked to micropumps that allow them to be independently perfused and sampled.

Source: Vanderbilt University