Researchers from Stanford have discovered that microscopic tissue growth in the brain continues in regions that also show changes in function.

The commonly held belief that brain tissue is slowly lost with age is now being questioned, according to a pair of new studies.

It was previously thought that excess neural connections are slowly pruned back throughout early childhood, until the brain’s structure becomes relatively stable.

However, a study published in Cerebral Cortex, as well as a study published in Science, suggest that this process may be more complicated than scientists previously thought.

Scientists discovered for the first time that microscopic tissue growth in the brain continues in regions that also show changes in function.

Kalanit Grill-Spector, a professor of psychology at Stanford and senior author of both papers, explained the focus of the studies.

“I would say it’s only in the last 10 years that psychologists started looking at children’s brains,” Grill-Spector said in a statement. “The issue is, kids are not miniature adults and their brains show that. “Our lab studies children because there’s still a lot of very basic knowledge to be learned about the developing brain in that age range.”

Grill-Spector and her colleagues examined the region of the brain that distinguishes faces from other objects.

In the Cerebral Cortex study, which was published in November, Grill-Spector’s team demonstrated that brain regions that recognize faces have a unique cellular make-up, while in the Science study, published in January, they found that the microscopic structures within the region change from childhood into adulthood over a timescale that mirrors improvements in people’s ability to recognize faces.

“We actually saw that tissue is proliferating,” Jesse Gomez, graduate student in the Grill-Spector lab and lead author of the Science paper, said in a statement. “Many people assume a pessimistic view of brain tissue: that tissue is lost slowly as you get older.

“We saw the opposite—that whatever is left after pruning in infancy can be used to grow.”

The research focused on the two regions of the brain that recognize faces and places because this identification is important in everyday functions.

“If you could walk across an adult brain and you were to look down at the cells, it would be like walking through different neighborhoods,” Gomez said. “The cells look different. They’re organized differently.”

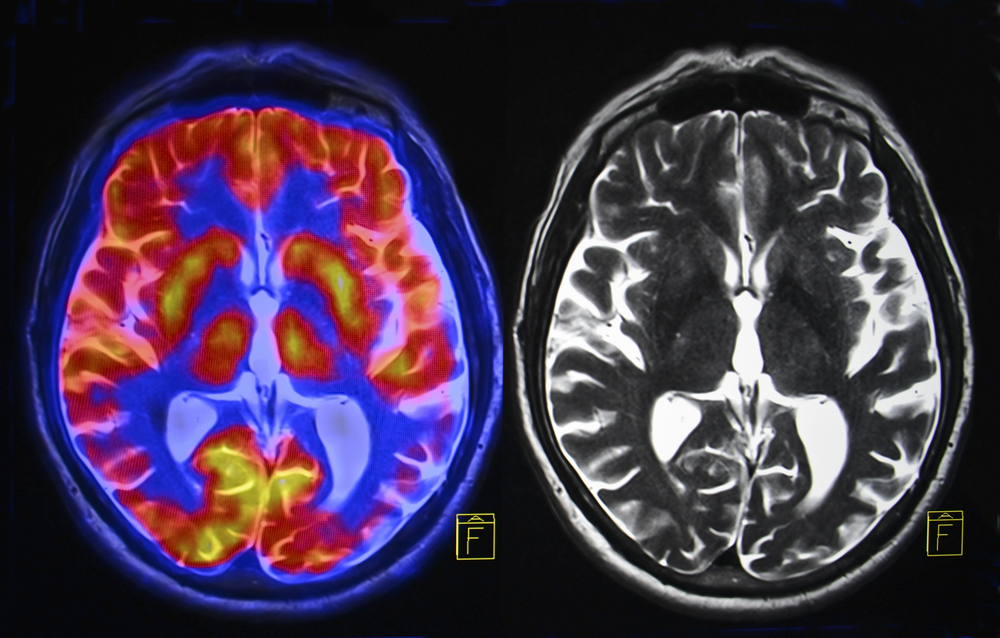

The Stanford group in collaboration with colleagues at the Institute of Neuroscience and Medicine, Research Centre Jülich, in Germany, examined thin tissue slices of post-mortem brains over the course of a year, matching brain regions identified with functional MRI in living brains with the corresponding brain slices.

After establishing that the two parts of the brain look different in adults, Grill-Spector wanted to see how these areas appear in children, particularly because the skills associated with the face region improve throughout adolescence.

During the experiment, the research team scanned the brains of 22 children between ages five and 12 and 25 adults between the ages of 22 and 28 using two types of MRI, one that indirectly measures brain activity and a quantitative one that measures the proportion of tissue to water in the brain.

They discovered that in addition to seeing a difference in brain activity in the two regions, the quantitative MRI showed that a certain tissue in the face region grows with development, which contributes to the tissue differences between face and place regions in adults.