Have you ever wondered why some people who sleep fewer hours feel groggy and unrefreshed, while others feel no effects at all?

A group of researchers at the University of Utah did—and as a result published a paper yesterday in Brain and Behavior, about finding patterns of neural connections in the brains of so-called “habitual short sleepers,” which suggest that some of these individuals may be efficient sleepers, but may also be more tired than they realize.

But lets’ start from the beginning—why do we sleep at all is still an enigma. One of the researchers called it “one of the most interesting questions in all science: why do we sleep in the first place?”

“Sleep is fascinating because it seems so unnecessary. How do organisms survive in a cruel world throughout evolution when they are immobilized for hours at a time,” Dr. Jeff Anderson, a radiologist and co-author of the paper told R&D Magazine in an exclusive interview.

Some of the leading notions are that sleep clears the brain of compounds accumulated throughout the day, and allows memories to move from short-term to long-term memory storage. It’s been said that for most, getting less than the recommended seven to nine hours of sleep a night ends in fatigue, irritability and some impairment in judgment and reasoning. Long-term short sleep period has been linked to a number of mental and physical health consequences, such as lesser cognitive performance, mood swings, obesity, coronary disease and all-cause mortality risk.

Then why do some people who get less than six hours of sleep feel no ill effects? In 2009, University of Utah neurologist Christopher Jones and colleagues found a rare genetic mutation that was associated with short-duration, efficient sleep. Several genetic factors are involved in sleep, and a combination of these factors could lead to some people feeling that they need less sleep than others.

To answer this question, Anderson, Jones and Paula Williams, psychology professor and co-author, along with psychology graduate student at University of Utah Brian Curtis, the first author of the new study, all looked into how people’s brains are wired together.

“One of our colleagues, Chris Jones, has been studying individuals who are short sleepers for several years, and participated in finding a gene that might be related in some individuals. Our interest was in looking at how these individuals might show differences in brain wiring,” Anderson told R&D.

Most cells in the brain are a small thin layer of gray matter cells along the surface. Everything else in the middle are connections between points on the surface and a few stations in between. Figuring out where those connections go—which points are connected and which aren’t in the gray matter is how the brain works, according to Anderson.

The set of brain connections is being studied with the Human Connectome Project, a multiuniversity consortium analyzing the network of connections in 1,200 individuals through MRI scans. So far data from around 900 people have been released, allowing the University of Utah team to access a large dataset of brain connectivity.

The researchers compared data from people who reported an adequate amount of sleep in the past month with those who said they sleep six hours or less a night. The short sleepers were then subdivided—those who reported daytime dysfunction, such as feeling drowsy to perform basic tasks or keeping up enthusiasm, and those who reported feeling fine.

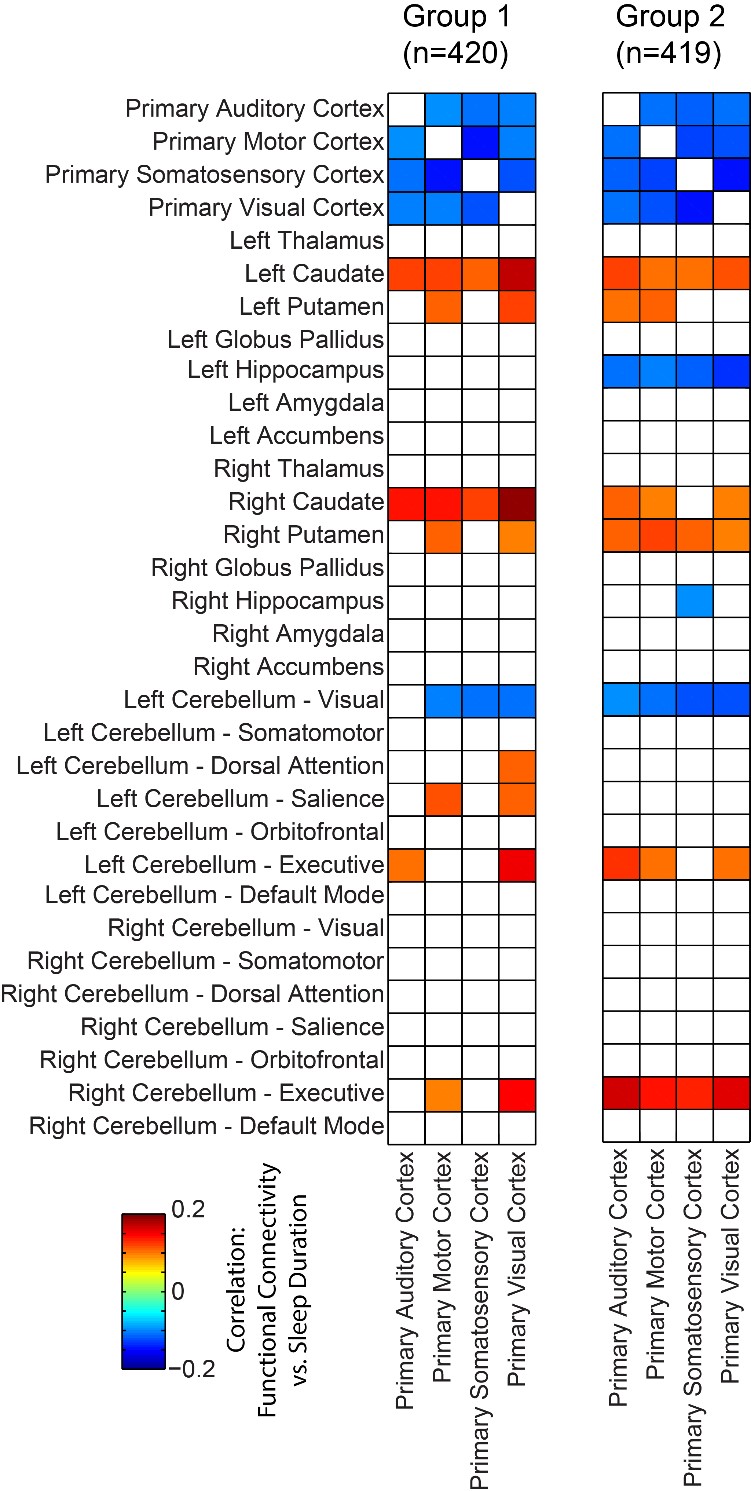

Correlation of sleep duration and functional connectivity between sensory/motor cortex, subcortical, and cerebellar regions for 2 subgroups of subjects. Color scale shows Pearson correlation coefficient between functional connectivity and sleep duration across subjects.

Both groups of short sleepers exhibited connectivity patterns more typical of sleep than wakefulness while in the MRI scanner, according to the paper. Anderson said that although people are instructed to stay awake while in the scanner, some short sleepers may have briefly drifted off, even those who denied dysfunction. According to Anderson, people are “notoriously poor” at being aware that they’ve fallen asleep for a minute or two. For short-sleepers who deny dysfunction, one theory is that their wake-up brain systems are constantly in overdrive. Which could mean that when they are trapped in boring fMRI scanners, they have nothing to do to keep them awake and therefore dose off.

“It looked like the short-sleepers showed brain connectivity changes that look like they were preferentially falling asleep. This was not only the case for short sleepers who reported being tired during the day, but also for the ones who said they felt fine,” Anderson added.

“We also found that the short sleepers denying dysfunction exhibited increased connectivity between the sensory cortices, amygdala, and hippocampus,” Williams told R&D. “Prior research suggests that this can occur in phasic REM states and may function, in part, to facilitate memory consolidation. If some short sleepers have rapid drops in sleep stages, both during night sleep and perhaps in daytime “microsleeps, this might contribute to their perception of daytime alertness.”

In other words, some short sleepers may be able to perform sleep-like memory consolidation and brain tasks throughout the day, reducing their need for sleep at night. Or they may be falling asleep during the day under low-stimulation conditions, often without realizing it.

The next phase of the team’s research, to be conducted at the University of Utah, will directly test whether short sleepers who deny dysfunction are actually doing fine. The researchers plan to recruit individuals who naturally sleep less than six hours a night. In addition to brain imaging, they will examine cognitive performance, including driving simulator testing, to get objective information about functioning. Getting insufficient sleep may affect people’s perception of their own dysfunction.

“There are likely some individuals who may be fine. Others may have advantages and disadvantages – they may have more awake, productive time, but they may also be vulnerable to falling asleep quickly when stimulation is removed,” Anderson said. “This could be a problem, for example, when driving or may affect health in many more subtle ways.”

The team also found that short sleepers appear to have high pain thresholds, which will also be examined in the next study conducted by the team.

“What we know from prior research is that ‘natural short sleepers’—those who routinely sleep less than six hours, regardless of their schedule (e.g., work week vs. weekend vs. vacation) — are high in behavioral activation and reward drive, often with hypomanic characteristics (e.g., high activity, distractibility, inflated self-esteem or grandiosity, engaging in pleasurable, but potentially risky behavior),” Williams concluded. “We believe they are likely engaging in highly stimulating activities that serve to override the physiological need to sleep. However, when forced to be in a low-stimulating environment, they may quickly lose wakefulness (which is what we may be seeing in the resting-state fMRI assessment). Given all the characteristics just described, they may not be able to accurately judge their functioning. “