Recent research shows that a type of antibiotic-resistant bacteria hospitals around the globe are struggling to fight is not new.

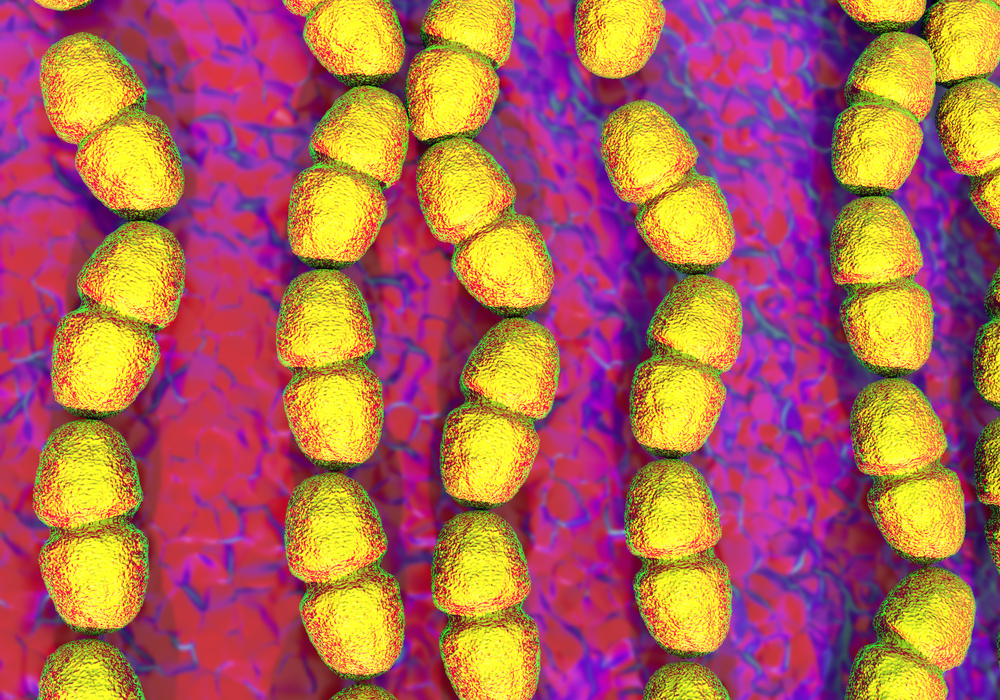

Researchers from Massachusetts Eye and Ear, the Harvard-wide Program on Antibiotic Resistance and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have discovered that enterococci—a leading antibiotic-resistant microbe—actually dates as far back as 450 million years ago, predating the age of the dinosaurs.

“By analyzing the genomes and behaviors of today’s enterococci, we were able to rewind the clock back to their earliest existence and piece together a picture of how these organisms were shaped into what they are today,” co-corresponding author Ashlee Earl, Ph.D., group leader for the Bacterial Genomics Group at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, said in a statement.

“Understanding how the environment in which microbes’ live leads to new properties could help us to predict how microbes will adapt to the use of antibiotics, antimicrobial hand soaps, disinfectants and other products intended to control their spread,” she added.

According to the researchers, bacteria first arose about four billion years ago and after animals emerged in the seas about 542 million years ago, bacteria learned to live in and on the animals. However, as animals evolved to the land they took the microbes with them.

The researchers found that all species of enterococci were naturally resistant to dryness, starvation, disinfectants and several antibiotics, making the bacteria particularly dangerous in a sterile hospital setting.

“We now know what genes were gained by enterococci hundreds of millions of years ago, when they became resistant to drying out, and to disinfectants and antibiotics that attack their cell walls,” study leader Michael Gilmore, Ph.D., senior scientist at Massachusetts Eye and Ear and the director of the Harvard Infectious Disease Institute.

They also found that because the bacteria are found in the intestines of the majority of land animals, they were also likely in the intestines of dinosaurs and the first millipede-like organism to crawl onto land.

After comparing the genomes of these bacteria, the researchers believe this theory to hold true.

The researchers also discovered that a new species of enterococci appeared each time a new type of animal emerged, including when a new type of animal arose after they first crawled onto land and when new types of animals arose after a mass extinction—particularly after the End Permian Extinction 251 million years ago.

Antibiotic resistant microbes are becoming an increasingly critical global health threat, with researchers searching for ways to combat these superbugs.

“These are now targets for our research to design new types of antibiotics and disinfectants that specifically eliminate enterococci, to remove them as threats to hospitalized patients,” Francois Lebreton, Ph.D., first author of the study and project leader for the Gilmore team, said in a statement.

The study was published in Cell.