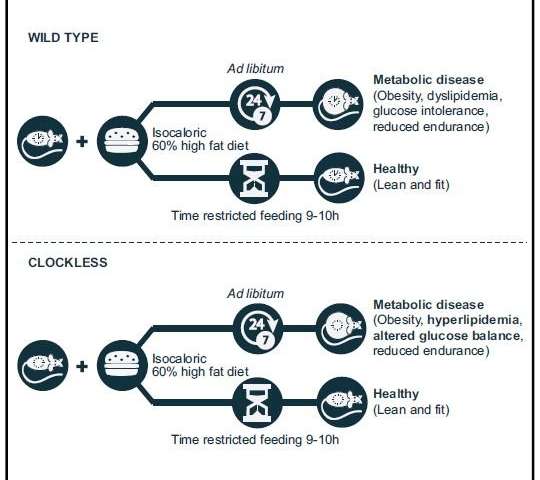

This graphical abstract shows that time-restricted feeding can improve metabolic health in mice with a compromised circadian clock. Credit: Chaix et al./Cell Metabolism

Scientists have discovered a previous unknown link between the disruption of the circadian clock and eating behavior.

New research by scientists from the Salk Institute suggests that limiting times when mice eat can correct obesity and other metabolic problems, even with an unhealthy diet.

“This was an unexpected finding,” Satchidananda Panda, a professor in the Regulatory Biology Laboratory at the Salk Institute and senior author of the study, said in a statement. “In the past, we have assumed that the circadian clock had a direct impact on maintaining a healthy metabolism, but this puts water on that fire.

“Our research suggests that the primary role of the clock is to produce daily eating-fasting rhythms, and that metabolic disease is only a consequence of disrupted eating behavior.”

The researchers examined three different strains of mice that had their circadian clocks disrupted by knocking out certain genes that are known to regulate internal timing. Some of the mice had access to food whenever they wanted, while others were restricted to a nine-to-10 hour window to eat.

However, both groups had the same calorie intake.

“This study showed us that the benefits of time-restricted feeding in maintaining body weight and reducing metabolic diseases are not dependent on an intact clock,” Amandine Chaix, a staff scientist at Salk and first author of the study, said in a statement.

The researchers previously found that having an intact circadian clock tells the mice when to eat—at least when they have access to healthy food. Mice with defective clocks often have disrupted eating patterns if they are allowed to eat whenever they want, many of which eventually show signs of metabolic disease, even when they are given only healthy food.

Other research has suggested that when normal mice are given access to food high in fat and sugar, the bad diet will override the circadian clock, leading the mice to eat randomly and develop metabolic diseases.

When the mice are restricted to an eight-to-12 hour window to eat, the researchers were able to prevent and reverse the health impacts of the unhealthy diet as measured by various factors like cholesterol and glucose levels, as well as stamina on a treadmill.

The time-restricted feeding also resulted in robust rhythms in circadian clock components.

“This earlier research led to the theory that that a robustly cycling circadian clock function is necessary to prevent metabolic diseases,” Panda said. “With this new research, our question was, ‘If the mice don’t have an internal clock telling when to eat, can we externally instruct mice when to eat, and will it prevent metabolic diseases?’

“And the answer we found was that for the metabolic parameters we studied, restricting the timing of feeding prevented health deterioration, even in the absence of a normal clock.”

The researchers’ next plan to look at how the circadian clock influences the central nervous system and in doing so regulates the urge to eat.

“We know that as people get older, they can start to lose their clocks,” Panda said. “These findings may suggest new ways to control compulsive eating in people whose clocks are disrupted.”

The study was published in Cell Metabolism.