This drawing shows the damaged outer wall of a carbon nanotube with nanosized graphene pieces (white patches), which facilitate the formation of catalytic sites made of iron (yellow) and nitrogen (red) atoms. The catalyst reduces oxygen to water. Image: Guosong Hong |

Fuel cells use

chemicals to create electricity. They are used, for example, to keep the lights

on for astronauts in orbiting space stations. They hold promise in a variety of

areas, such as fuel-cell cars. But the high price of catalysts used inside the cells

has provided a roadblock to widespread use.

Now, nanoscale

research at Stanford

University has found a

way to reduce the cost.

Multiwalled carbon

nanotubes riddled with defects and impurities on the outside could eventually

replace some of the expensive platinum catalysts used in fuel cells and

metal-air batteries, according to Stanford scientists. Their findings

are published in an online edition of Nature

Nanotechnology.

“Platinum is

very expensive and thus impractical for large-scale commercialization,”

said Hongjie Dai, a professor of chemistry at Stanford and co-author of the

study. “Developing a low-cost alternative has been a major research goal

for several decades.”

Over the past five

years, the price of platinum has ranged from just below $800 to more than

$2,200 an ounce. Among the most promising low-cost alternatives to platinum is

the carbon nanotube—a rolled-up sheet of pure carbon, called graphene, that’s

one atom thick and more than 10,000 times narrower a human hair. Carbon

nanotubes and graphene are excellent conductors of electricity and relatively

inexpensive to produce.

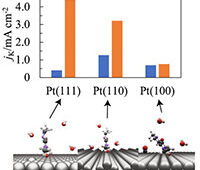

For the study, the

Stanford team used multiwalled carbon nanotubes consisting of two or three

concentric tubes nested together. The scientists showed that shredding the

outer wall, while leaving the inner walls intact, enhances catalytic activity

in nanotubes, yet does not interfere with their ability to conduct electricity.

“A

typical carbon nanotube has few defects,” said Yanguang Li, a postdoctoral

fellow at Stanford and lead author of the study. “But defects are actually

important to promote the formation of catalytic sites and to render the

nanotube very active for catalytic reactions.”

Unzipped

For the study, Li and his coworkers treated multiwalled nanotubes in a chemical

solution. Microscopic analysis revealed that the treatment caused the outer

nanotube to partially unzip and form nanosized graphene pieces that clung to

the inner nanotube, which remained mostly intact.

“We found that

adding a few iron and nitrogen impurities made the outer wall very active for

catalytic reactions,” Dai said. “But the inside maintained its

integrity, providing a path for electrons to move around. You want the outside

to be very active, but you still want to have good electrical conductivity. If

you used a single-wall carbon nanotube you wouldn’t have this advantage,

because the damage on the wall would degrade the electrical property.”

In fuel cells and

metal-air batteries, platinum catalysts play a crucial role in speeding up the

chemical reactions that convert hydrogen and oxygen to water. But the partially

unzipped, multiwalled nanotubes might work just as well, Li added. “We

found that the catalytic activity of the nanotubes is very close to

platinum,” he said. “This high activity and the stability of the

design make them promising candidates for fuel cells.”

The researchers

recently sent samples of the experimental nanotube catalysts to fuel cell

experts for testing. “Our goal is to produce a fuel cell with very high

energy density that can last very long,” Li said.

Multiwalled nanotubes

could also have applications in metal-air batteries made of lithium or zinc.

“Lithium-air

batteries are exciting because of their ultra-high theoretical energy density,

which is more than 10 times higher than today’s best lithium ion

technology,” Dai said. “But one of the stumbling blocks to

development has been the lack of a high-performance, low-cost catalyst. Carbon

nanotubes could be an excellent alternative to the platinum, palladium, and

other precious-metal catalysts now in use.”

Controversial

sites

The Stanford study might also have resolved a long-standing scientific

controversy about the chemical structure of catalytic active sites where oxygen

reactions occur. “One group of scientists believes that iron impurities

are bonded to nitrogen at the active site,” Li said. “Another group

believes that iron contributes virtually nothing, except to promote active

sites made entirely of nitrogen.”

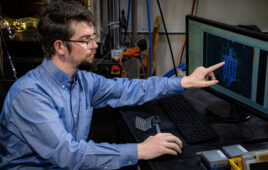

To address the

controversy, the Stanford team enlisted scientists at Oak Ridge National

Laboratory to

conduct atomic-scale imaging and spectroscopy analysis of the nanotubes. The

results showed clear, visual evidence of iron and nitrogen atoms in close

proximity.

“For the first

time, we were able to image individual atoms on this kind of catalyst,”

Dai said. “All of the images showed iron and nitrogen close together,

suggesting that the two elements are bonded. This kind of imaging is possible,

because the graphene pieces are just one atom thick.”

Dai noted that the

iron impurities, which enhanced catalytic activity, actually came from metal

seeds that were used to make the nanotubes and were not intentionally added by

the scientists. The discovery of these accidental yet invaluable bits of iron

offered the researchers an important lesson. “We learned that metal

impurities in nanotubes must not be ignored,” Dai said.

Source: Stanford University