Most people simply take ibuprofen when they get a headache. But for someone with hydrocephalus — a potentially life-threatening condition in which excess fluid builds up in the brain — a headache can indicate a serious problem that can result in a hospital visit, thousands of dollars in scans, radiation and sometimes surgery.

A new wireless, Band-Aid-like sensor developed at Northwestern University could revolutionize the way patients manage hydrocephalus and potentially save the U.S. health care system millions of dollars.

A Northwestern Medicine clinical study successfully tested the device, known as a wearable shunt monitor, on five adult patients with hydrocephalus. The findings were published in Science Translational Medicine.

Hydrocephalus can affect adults and children. Often the child is born with the condition, whereas in adults, it can be acquired from some trauma-related injury, such as bleeding inside the brain or a brain tumor.

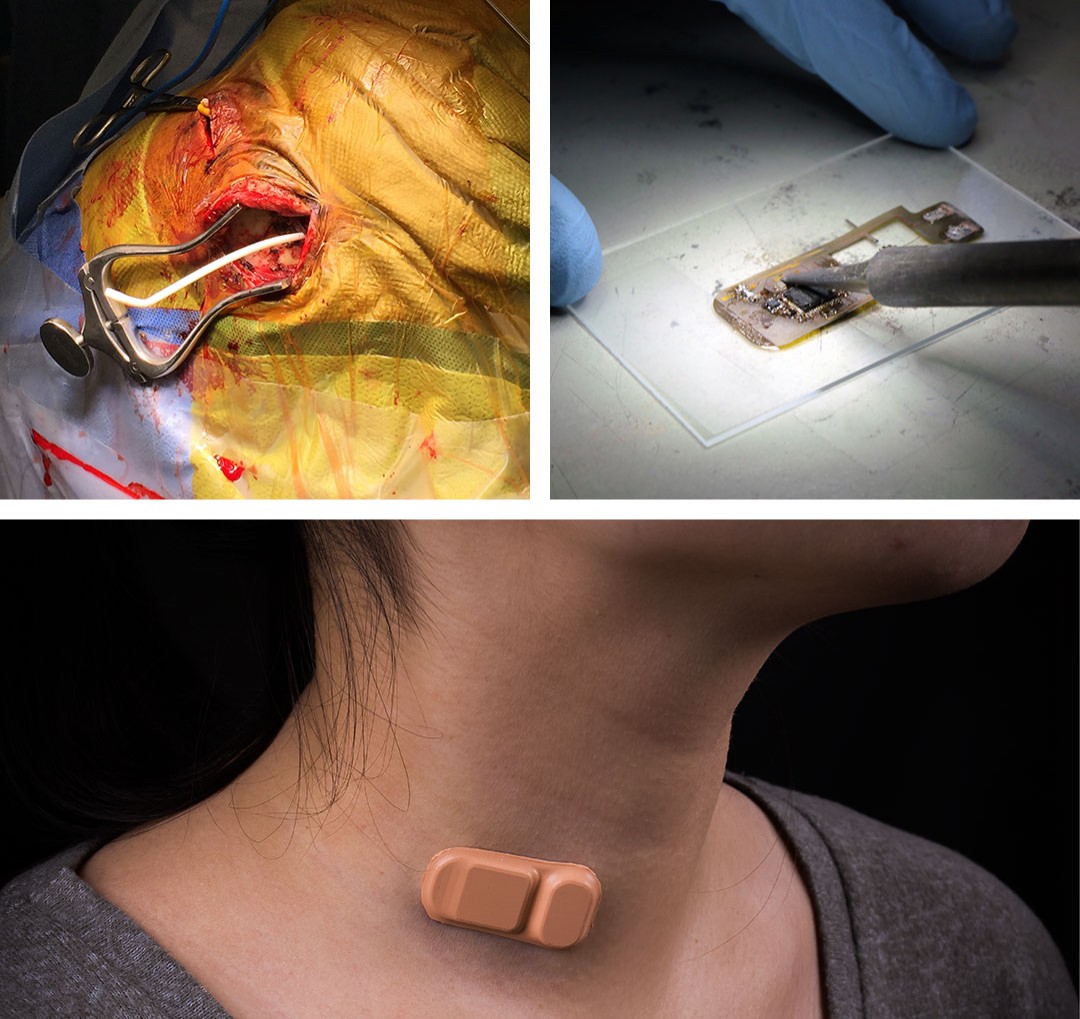

The current standard of care involves the surgical implantation of a straw-like catheter known as a “shunt,” which drains the excess fluid out of the brain and into another part of the body.

Shunts have a nearly 100 percent failure rate over 10 years, and diagnosing shunt failure is notoriously difficult. More than a million Americans live with shunts and the constant threat of failure.

The groundbreaking new sensor, developed by the Rogers Research Group at Northwestern, could create immense savings and improve the quality of life for nearly a million people in the U.S. alone.

When a shunt fails, the patient can experience headaches, nausea and low energy. A patient experiencing any of these symptoms must visit a hospital because if their symptoms are caused by a malfunctioning shunt, it could be life threatening.

Once at the hospital, the patient must get a CT scan or an MRI and sometimes must undergo surgery to see if the shunt is working properly.

Top left: A shunt protruding from the brain during surgery. Top right: A researcher solders a new wearable shunt monitor. Bottom: A woman wears a new wearable shunt monitor on her neck.

The new sensor allowed patients in the study to determine within five minutes of placing it on their skin if fluid was flowing through their shunt.

The soft and flexible sensor uses measurements of temperature and heat transfer to non-invasively tell if and how much fluid is flowing through.

“We envision you could do this while you’re sitting in the waiting room waiting to see the doctor,” says co-lead author Siddharth Krishnan, a fifth-year Ph.D. student in the Rogers Research Group.

“A nurse could come and place it on you and five minutes later, you have a measurement.”

A device like this would be life changing for Willie Meyer, 26, who has undergone 190 surgeries, spent virtually every holiday in the emergency room and almost missed his high school graduation because of emergency brain surgeries.

Meyer’s mother, Beth, said she learned Willie had hydrocephalus when he was two years old after complaining that “his hair hurt.”

Symptoms of a malfunctioning shunt, such as headaches and fatigue, are similar to symptoms of other illnesses, which causes confusion and stress for caregivers.

“Every time your kid says they have a headache or feels a little sleepy, you automatically think, ‘Is this the shunt?’” says co-senior author Dr. Matthew Potts, assistant professor of neurological surgery at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and a Northwestern Medicine physician.

“We believe that this device can spare patients a lot of the danger and costs of this process.”

Co-lead author Dr. Amit Ayer, who has treated Willie’s hydrocephalus for the last four years, says his patients are a driving force behind his motivation to get the device to market.

“Our patients want to know when they can actually use the device and be part of the trial,” said Ayer, who is a neurosurgery resident at Northwestern Medicine and a student at Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern.

“I want to get it out there, so we can help make their lives better.”

Source: Northwestern University