LungMAP.net is a publicly available resource for accessing data collected by all of the LungMAP research centers. (Image: Courtesy of TACC)

In 2016, over a dozen scientists and engineers toured a neonatal intensive care unit, the section of the hospital that specializes in the care of ill or premature newborn infants. The researchers had come together from all around the country, and brought with them a wide variety of expertise. Visiting the newborns helped put into perspective the reason for this gathering of researchers—lung development—and for their collaboration over the coming years.

James Carson of the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) was one of the research scientists in this group. He and his colleagues have been working on the Molecular Atlas of Lung Development Program, known as LungMAP, funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health.

For the past five years, the LungMAP team has been building an open access data resource of the developing lungs in both laboratory mice and humans, in order to further our knowledge of how the lung begins to breathe. The resource contains highly detailed datasets of genes, proteins, lipids and metabolites in the context of cell types and lung anatomy. Carson says LungMAP is now a uniquely comprehensive data resource on lung development.

“Thousands of babies are born prematurely every day,” says Carson, who is a co-principal investigator on the project. “With normal development, the lung has the shape and cell types to breathe plenty of air upon birth. However, a premature lung may not be able to breathe enough air at birth, and it is a challenge to help the lung develop normally those first few months. There can be health effects that continue into adulthood without proper lung development.”

Babies born before week 37 of pregnancy are considered preterm. Preterm babies face a higher risk for one or more complications after delivery, and in many cases these involve the lungs. A baby’s lungs are typically considered mature by week 36. However, not all babies develop at the same rate, so there can be exceptions.

Breathing problems in premature babies are caused by an immature respiratory system. Immature lungs in premature babies often lack surfactant, a liquid that coats the inside of the lungs and helps keep them open. Without surfactant, a premature baby’s lungs can’t expand and contract normally.

“We’re gathering data that’s never been collected before,” Carson says. “In the past, how scientists described lung development was limited by the methods available for measuring and capturing pictures. However, with access to the latest technologies for detecting molecules, we’re learning about new types and subtypes of cells, and passing that information onto the whole community of lung researchers.”

The first 5-year phase of the project, which is now in its final months, focused on characterizing the details of healthy lung development in mice and humans. The researchers are hoping to be part of the second phase of the project which will include a new focus on understanding diseases in the human lung.

Collaboration Across the Country

The large, collaborative project involves researchers at universities, medical schools, federal laboratories, and companies. They are collectively organized into six separate centers, four providing data collection and research, one providing human tissue samples, and one serving as the data coordinating center.

TACC is part of the Center of Lung Development Imaging and Omics, which also includes Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), Baylor College of Medicine and the University of Washington. TACC’s role is focused on providing data storage and curation of tens of thousands of images, most of which are larger than 100 megapixels.

Charles Ansong at PNNL is the principal investigator of this research center. He and the project team at PNNL use proteomics and lipidomics to determine how much of each protein and lipid are in a tissue sample.

“We’ve done an excellent job over the past five years in pushing technology development to make measurements in smaller and smaller tissue samples,” Ansong said. “Now we’re able to perform single cell proteomics—so that given a single cell, we can detect and measure quantity for hundreds of different proteins.”

The data in mice is collected both before and after birth, in order to give insight into all the stages of lung development. A human baby born prematurely would have cells in the lung similar to those found in a mouse prior to its birth. This information helps researchers understand what cells in the lung need to do to get to the point where they can support breathing properly.

“We’re trying to figure out all the different cell types and where those cell types are,” Ansong said. “Sometimes cells start as one type and then change to another type, depending on what stage of development they’re in. The datasets from our center allow researchers to see where genes, proteins, lipids, and metabolites are located and in what quantities.”

Carson says that it’s not as useful to look at genes that every cell has in equal amounts. “We’re more interested in genes that are unique to a specific cell type and function. With help from our collaborators at other LungMAP centers, I think we succeeded in identifying the most important genes for understanding lung development.”

Cecilia Ljungberg at the Baylor College of Medicine collects the images from the donor mice. She also performs the tissue preparation, sectioning, and a technique called high-throughput in situ hybridization. This process is used to reveal the location of specific “messenger” ribonucleic acid sequences in tissues, a crucial step for understanding the organization, regulation, and function of genes.

From there, Ljungberg and her colleagues use a high resolution microscope to take images of these tissue sections, images which can approach a gigapixel in size—many times the information captured by a 10 megapixel digital camera—and upload them into CyVerse’s BisQue, a powerful computational tool which provides life scientists the ability to handle huge datasets, perform analyses, and evaluate, curate, and share images. TACC is part of the advanced computing resources that are the foundation of the CyVerse infrastructure.

“The amount of data collected is pretty staggering,” Ljungberg said. “So far, we have looked at more than 700 different genes at four different developmental stages in mouse, and collected more than 20,000 images, with each image focused on a particular gene at a particular age.”

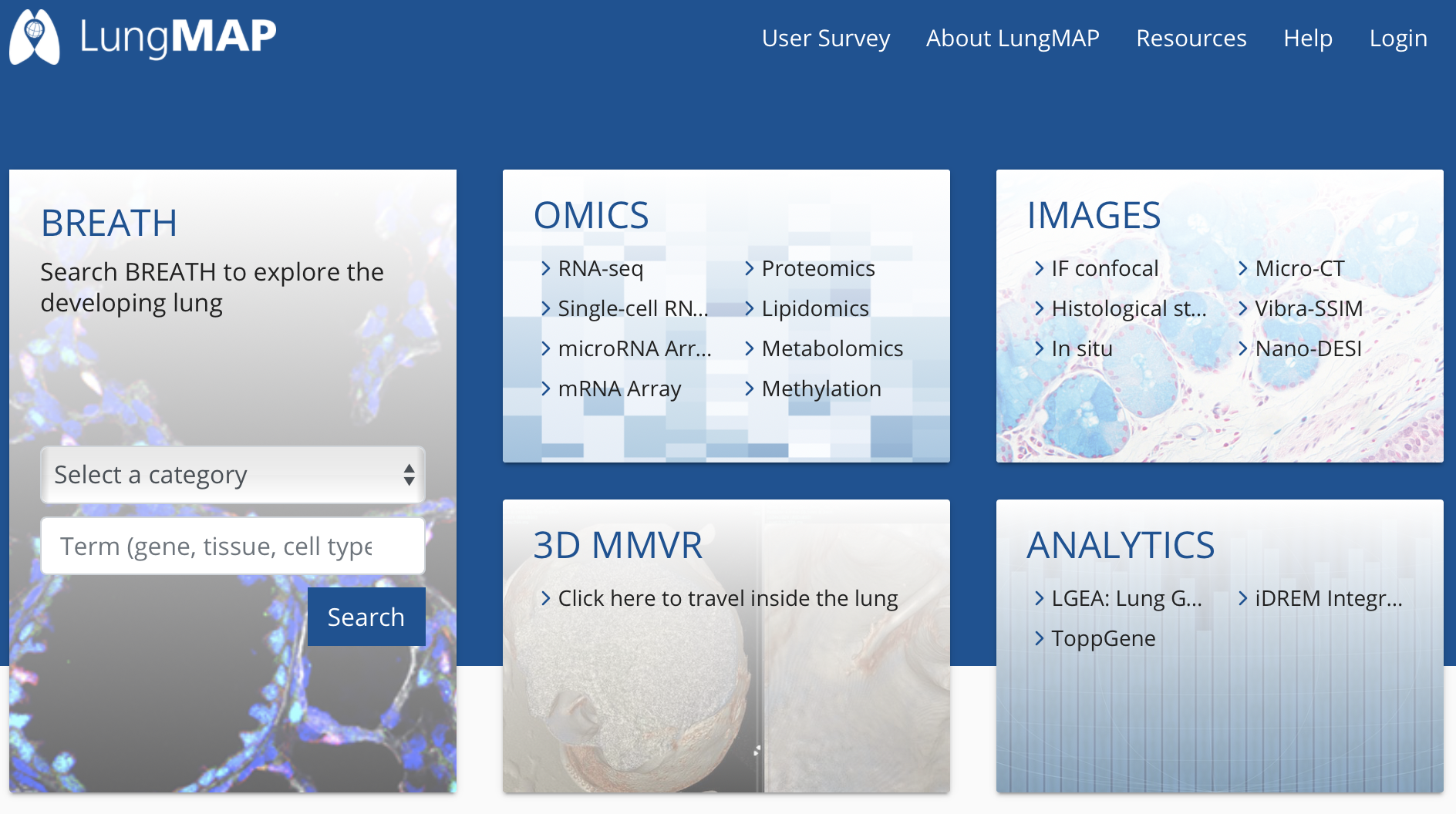

TheLungMAP website provides access to a repository of data and metadata to support scientific explorations in lung development. Images and other data types are standardized and organized within a common ontology, or set of concepts and categories that shows their properties and the relations between them.

“We want high quality images from each stage of lung development to be included on the website,” Carson says. “LungMAP.net contains all of the data from the different research centers. For any given molecule, one can access a summary page of activity across development, and you can begin to see trends in the different cell types.”

Data Collection Techniques

The PNNL- and TACC-led team leverage three types of data collection: 1) high-throughput in situ hybridization—a technique used here to detect RNA sequences in cells across a section of tissue; 2) nanospray desorption electrospray ionization (nano-DESI), a high-resolution technique for mass spectrometry imaging, to provide fundamental knowledge about where specific lipids and metabolites are found in the lungs; 3) and highly sensitive “omics” approaches at scales from whole tissue to region-specific to cell-type-specific.

Ansong says, “The integrative spatiotemporal data generated, from genes to proteins to lipids/metabolites, provides a complementary and comprehensive view of genotype to phenotype relationships that is unprecedented in understanding normal lung development.”

Researchers and doctors are able to explore this data to better understand what normal lung development looks like. This then allows them to understand what happens when a baby is born prematurely, its organs not fully formed, and what interventions may cultivate continued lung growth.

What’s Next?

At this point in the project, the focus is on human lungs. The team is wrapping up the processing of approximately 5,000 images representing normal lung development in humans. With mice, each tissue section consists of a cross-section of the entire lung or lung lobe. However, human lungs are a lot larger, so it’s not optimal to image cross-sections of the entire lung using these methods. “The cross-section of the entire human lung doesn’t fit on a standard glass slide, so we utilize sampling strategies instead” Carson says.

In the first phase of LungMAP, the NHLBI sought large quantities of highly detailed data sets using high throughput imaging and omics technologies. “We delivered on that greatly, and did a really good job of pushing the technology development, too,” Ansong said.

“For Phase two, they’re interested in progressing to high resolution 3D imaging and single cell type technologies. And they’re interested in taking out the mouse and focusing on human lungs and diseases, which is good because by studying the human we’re getting closer to direct impacts,” he said.

Carson notes that Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is a natural fit to study. It’s a form of chronic lung disease that affects newborns (mostly premature) and infants, resulting from damage to the lungs caused by respirators and long-term use of oxygen. Most infants recover from BPD, but some may have long-term breathing difficulty.

LungMAP is laying the groundwork for these investigations. The researchers involved believe the primary benefits will be felt in the near future. “Our goal is to fully understand the lung before and after birth so that doctors can apply new strategies to increase positive health outcomes for premature babies,” Carson said.

The article, “Spatial distribution of marker gene activity in the mouse lung during alveolarization,” was published in February 2019 in the journal Data in Brief (Elsevier). The authors are M. Cecilia Ljungberg, Mayce Sadi, Yunguan Wang, Bruce J. Aronow, Yan Xu, Rong J. Kao, Ying Liu, Nathan Gaddis, Maryanne E. Ardini-Poleske, Tipparat Umrod, Namasivayam Ambalavanan, Teodora Nicola, Naftali Kaminski, Farida Ahangari, Ryan Sontag, Richard A. Corley, Charles Ansong, and James P. Carson. This data was generated as a resource for the public research community through support of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) LungMAP program funding (U01 HL122703) and by an NIH Shared Resource equipment grant (S10 OD016167).