Random number generators have played a critical role in an historic experiment that gives the strongest refutation to date of Albert Einstein’s principle of “local realism,” which says that the universe obeys laws, not chance, and that there is no communication faster than light.

Random number generators have played a critical role in an historic experiment that gives the strongest refutation to date of Albert Einstein’s principle of “local realism,” which says that the universe obeys laws, not chance, and that there is no communication faster than light.

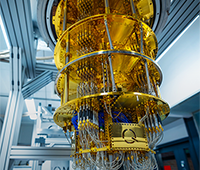

As described in TU Delft’s Ronald Hanson’s group Web, the Delft experiment first “entangled” two electrons trapped inside two different diamond crystals, and then measured the electrons’ orientations. In quantum theory, entanglement is powerful and mysterious: mathematically the two electrons are described by a single “wave-function” that only specifies whether they agree or disagree, not which direction either spin points. In a mathematical sense, they lose their identities. “Local realism” attempts to explain the same phenomena with less mystery, saying that the particles must be pointing somewhere, we just don’t know their directions until we measure them.

When measured, the Delft electrons did indeed appear individually random while agreeing very well. So well, in fact, that they cannot have had pre-existing orientations, as realism claims. This behavior is only possible if the electrons communicate with each other, something that is very surprising for electrons trapped in different crystals. But here’s the amazing part: in the Delft experiment, the diamonds were in different buildings, 1.3 kilometers away from each other. Moreover, the measurements were made so quickly that there wasn’t time for the electrons to communicate, not even with signals traveling at the speed of light. This puts “local realism” in a very tight spot: if the electron orientations are real, the electrons must have communicated. But, if they communicated, they must have done so faster than the speed of light. There’s no way out, and local realism is disproven. Either God does play “dice” with the universe, or electron spins can talk to each other faster than the speed of light.

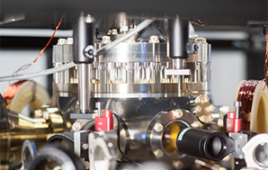

This amazing experiment called for extremely fast, unpredictable decisions about how to measure the electron orientations. If the measurements had been predictable, the electrons could have agreed in advance which way to point, simulating communications where there wasn’t really any, a gap in the experimental proof known as a “loophole.” To close this loophole, the Delft team turned to researchers at The Institute of Photonic Sciences (ICFO). The team composed of Carlos Abellan, Waldimar Amaya, Valerio Pruneri and Morgan Mitchell hold the record for the fastest quantum random number generators. ICFO designed a pair of “quantum dice” for the experiment: a special version of their patented random number generation technology, including very fast “randomness extraction” electronics. This produced one extremely pure random bit for each measurement made in the Delft experiment. The bits were produced in about 100 nanoseconds, the time it takes light to travel just 30 meters, not nearly enough time for the electrons to communicate.

“Delft asked us to go beyond the state-of-the-art in random number generation. Never before has an experiment required such good random numbers in such a short time.” Says Carlos Abellán, a Ph.D. student at ICFO and a co-author of the Delft study.

For the ICFO team, the participation in the Delft experiment was more than a chance to contribute to fundamental physics. Professor Mitchell comments: “Working on this experiment pushed us to develop technologies that we can now apply to improve communications security and high-performance computing, other areas that require high-speed and high-quality random numbers.”

With the help of ICFO’s quantum random number generators, the Delft experiment gives a nearly perfect disproof of Einstein’s world-view, in which “nothing travels faster than light” and “God does not play dice.” At least one of these statements must be wrong. The laws that govern the Universe may indeed be a throw of the dice.

The experiment was published online October 21, 2015, in Nature. Link to the paper