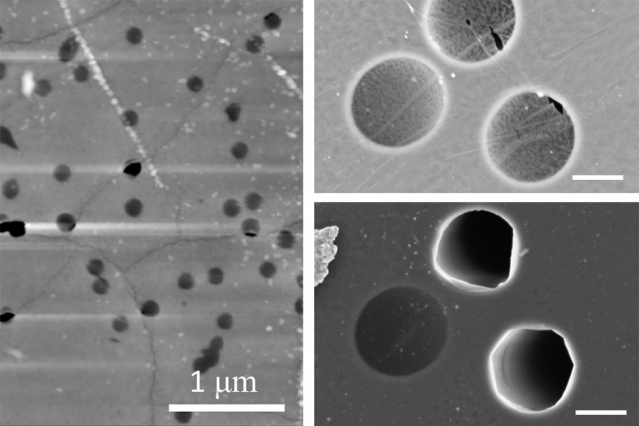

On the left, an atomic-force microscopy image shows a nanoporous graphene membrane after a burst test at 100 bars. The image shows that failed micromembranes (the dark black areas) are aligned with wrinkles in the graphene. On the right, two zoomed-in scanning electron microscopy images of graphene membranes show the before (top) and after of a burst test at pressure difference of 30 bars. The images illustrate that membrane failure is associated with intrinsic defects along wrinkles. Credit: Rohit Karnik

For the first time, a graphene membrane has been designed that can withstand up to 100 bars of pressure.

Rohit Karnik, an associate professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Department of Engineering, said the discovery could open graphene to a number of new applications, including desalination, where filtration membranes that can withstand high-pressure flows can more efficiently remove salt from seawater.

“This is a fundamental study at this point, and what it shows is the possibility that one can design graphene membranes that can withstand high pressures,” Karnik said during an exclusive interview with R&D Magazine. . “This in itself doesn’t immediately lead to any application but it is basically a demonstration that you can design graphene membranes to withstand high pressures.”

According to Karnik, the research indicates which substrate designs are better to support graphene under higher pressures and that when graphene was placed over substrates with larger pores it failed to withstand even low pressure.

“Consistent with theory, the membranes were found to withstand higher pressures when placed on porous supports with smaller pore diameters but failure occurred over a surprisingly broad range of pressures, attributed to heterogeneous susceptibility to failure at wrinkles, defects and slack in the suspended graphene,” the study, which was published in Nano Letters, states.

For example, one micron pores will not allow graphene to withstand very high pressure, while when graphene was placed over pores 200 nanometers or less in diameter it was able to withstand 100 bars of pressure.

Currently, commercial membranes are used to desalinate water under applied pressures of about 50 to 80 bars, but if membranes are able to withstand pressure of 100 bars or greater it would enable more effective desalination of seawater by recovering more fresh water. High-pressure membranes would allow extremely salty water including leftover brine from desalination to be purified.

The researchers were able to set up experiments to push graphene to the height of its pressure tolerance after growing sheets of graphene using a technique called chemical vapor deposition—a process where the substrate is exposed to one or more volatile precursors that react and/or decompose on the substrate surface to produce the desired deposit.

Single layers of graphene were placed on thin sheets of porous polycarbonate with each sheet designed with pores of a size ranging from 30 nanometers to three microns in diameter.

The researchers placed the graphene-polycarbonate membranes in the middle of a chamber, into the top half of where they pumped argon gas, using a pressure regulator to control the gas pressure and flow rate. They also measured the gas flow rate in the bottom half of the chamber, where any increase in the bottom half’s flow rate indicates that parts of the graphene membrane failed to withstand the pressure.

Another result of the study is that the copper wrinkles present in graphene after it is synthesized couldn’t withstand much pressure. Parts of the graphene that lay along wrinkles failed to withstand pressure as low as 30 bars, while graphene without wrinkles remained intact at pressures up to 100 bars.

While Karnik said they did not necessarily push graphene to its pressure limits, the study did show that graphene can be used in a number of new ways that aren’t currently being explored to the fullest.

“We have been looking at nanoporous graphene and trying to understand how much transport happens to a nanoporous graphene,” Karnik said. “If it can withstand high pressure then in theory it opens up possibilities of operating graphene membranes at very high pressures where other membranes cannot easily operate.”

According to Karnik, one of the key aspects of graphene that make it a good option for a number of scientific applications is that it is a single layered material that is not subject to change in its structure, while polymers will change properties when exposed to different solvents or different pressures.

“The fact that graphene is a rigid lattice makes it immune to those changes,” Karnik said.