Seeing is believing when it comes to nanoparticle self-assembly. A team of University of Illinois engineers is observing the interactions of colloidal gold nanoparticles inside tiny aquarium-like sample containers to gain more control over the self-assembly process of engineered materials.

Self-assembling colloidal nanoparticles are one of the things that make stuff like LED displays, solar cells and batteries work. Researchers study these nanoparticles with still images using high-powered electron microscopes, but because colloidal nanoparticles interact through motions in liquids, traditional electron microscopy-based observation methods cannot capture the interactions that occur when these nanoparticles self-assemble, says Qian Chen, a professor of materials science and engineering and co-author of a new study.

“The colloid self-assembly process has always been a bit of a black box,” Chen says. “The particles behave like atoms and molecules, which allows us to use classical chemistry and physics theories to model their behavior. This new method, called liquid-phase transmission electron microscopy, allows us to see exactly what is happening.”

The team’s new method, published in Nature Communications, also shows that the shape of nanoparticles can control the types of materials formed.

“One challenge in nanotechnology is conquering our inability to control the process of artificial assembly,” Chen says. “By working with particles of different shapes, we can control how the particles stack up together, almost like playing with tiny Legos toys. This type of control will make a difference in a material’s properties and application.”

“We can follow the trajectory of the nanoparticles, precisely and continuously, which gives us the power to map out the assembly rate laws quantitatively,” says postdoctoral researcher and lead author Juyeong Kim. “Particular shapes prefer to attach in a way similar to how molecules connect into big polymers, and we can reproduce those conditions, which is a huge step forward in the fundamental understanding and the control over nanoparticle self-assembly.”

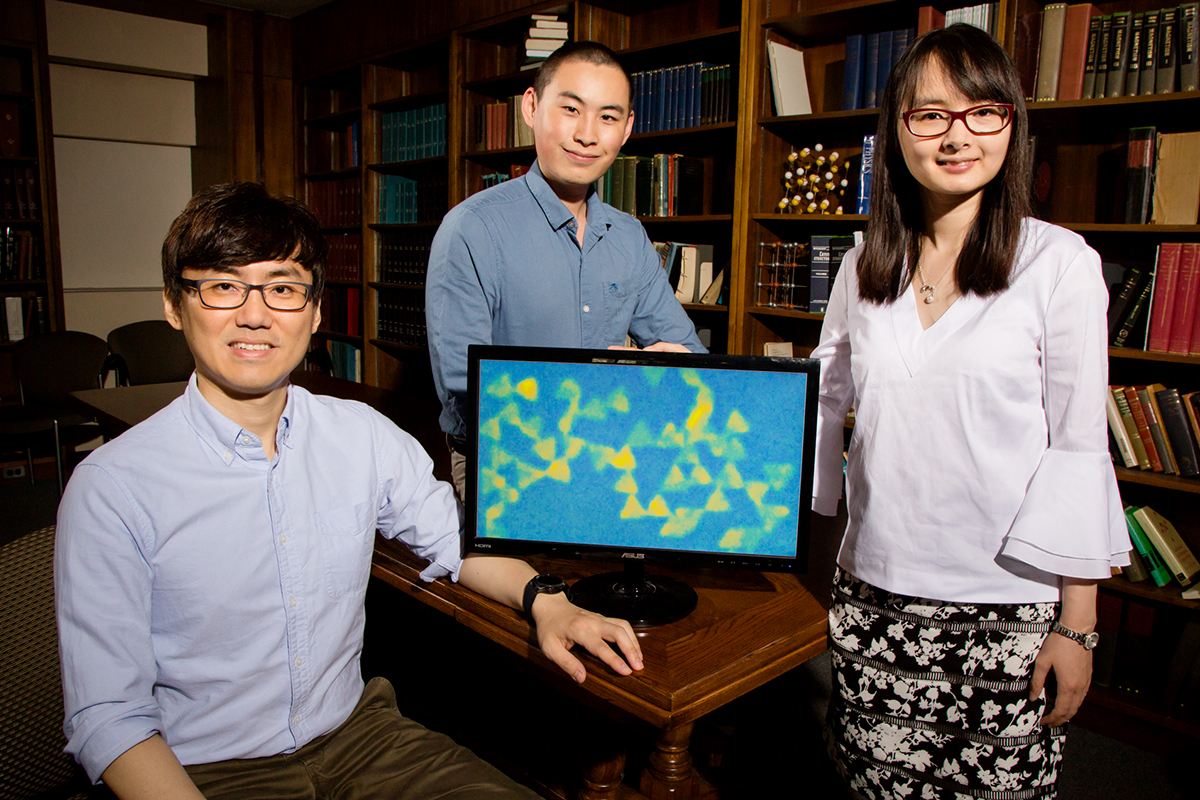

University of Illinois postdoctoral researcher Juyeong Kim, left, graduate student Zihao Ou and professor Qian Chen have developed a new technique for observing colloidal nanoparticles while they interact and self-assemble. Image: L. Brian Stauffer

The group chose to experiment using gold for a reason.

“Gold shows excellent contrast under TEM because it is a heavy element, making it easy to observe,” says graduate student and co-author Zihao Ou. “It is also a very stable and generally nontoxic element, which is beneficial for applications within the human body, like medicine.”

“Colloidal gold contains a property that allows it to concentrate electromagnetic radiation, like light waves, allowing it to generate heat,” Kim says. “One possible application of this is something called photothermal therapy, where we can inject colloidal gold into a patient to target cancer cells and destroy them with heat.”

Chen also envisions the liquid-phase TEM method being used to study the structure of proteins and microorganisms within the human body. Proteins need to be frozen or crystallized for analysis, which is not ideal. Her group is now looking at proteins in liquid environments using liquid-phase TEM to see how they self-assemble and change their shape.

The U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences – Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering through the Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory at the U. of I. supported this study.