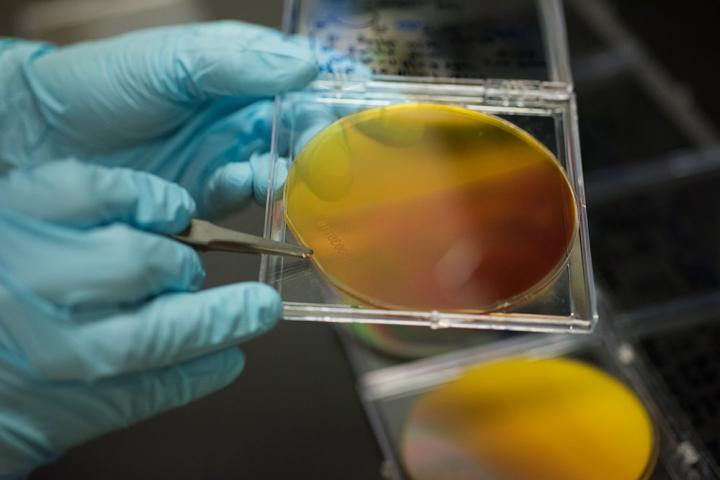

Caption: Scientists at JCAP create new materials by spraying combinations of elements onto thin plates. Credit: Caltech

A group of scientists have found a bevy of new materials that can be potentially used in solar fuels.

Researchers at Caltech and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have developed a process that speeds up the discovery of commercially viable solar fuels that could replace coal, oil and other fossil fuels.

Solar fuels are created using only sunlight, water and carbon dioxide and researchers are exploring a range of target fuels including hydrogen gas and liquid hydrocarbons, where producing any of these fuels involve splitting water.

In a water molecule, the hydrogen atoms are extracted and then can be reunited to create highly flammable hydrogen gas or combined with carbon dioxide to create hydrocarbon fuels. This would create a plentiful and renewable energy source.

However, water molecules do not simply break down when sunlight shine on them and need assistance from a solar-powered catalyst.

Scientists have been attempting to develop low-cost and efficient materials called photoanodes that are capable of splitting water using visible light as an energy source.

In the last 40 years, researchers have only identified 16 photoanode materials. However, a new high-throughput method of identifying new materials had led to 12 promising leads for new photoanodes.

“This integration of theory and experiment is a blueprint for conducting research in an increasingly interdisciplinary world,” John Gregoire, the Joint Center for Artificial Photosynthesis thrust coordinator for Photoelectrocatalysis and leader of the High Throughput Experimentation group, said in a statement. “It’s exciting to find 12 new potential photoanodes for making solar fuels but even more so to have a new materials discovery pipeline going forward.”

Berkeley Lab’s Jeffrey Neaton explained the study.

“What is particularly significant about this study, which combines experiment and theory, is that in addition to identifying several new compounds for solar fuel applications we were also able to learn something new about the underlying electronic structure of the materials themselves,” Neaton said in a statement.

Scientists previously relied on cumbersome testing of individual compounds to assess their potential for use in specific applications. However, the new process combines computational and experimental approaches by first mining a materials database for potentially useful compounds and screening it based on the properties of the materials. The researchers then can rapidly test the most promising candidates using high-throughput experimentation.

The research team explored 174 metal vanadates—compounds that contain vanadium and oxygen along with one other element.

According to Gregoire, the research reveals how different choices for the third element can produce materials with different properties and reveals how to “tune” those properties to make a better photoanode.

“The key advance made by the team was to combine the best capabilities enabled by theory and supercomputers with novel high throughput experiments to generate scientific knowledge at an unprecedented rate,” Gregoire said.