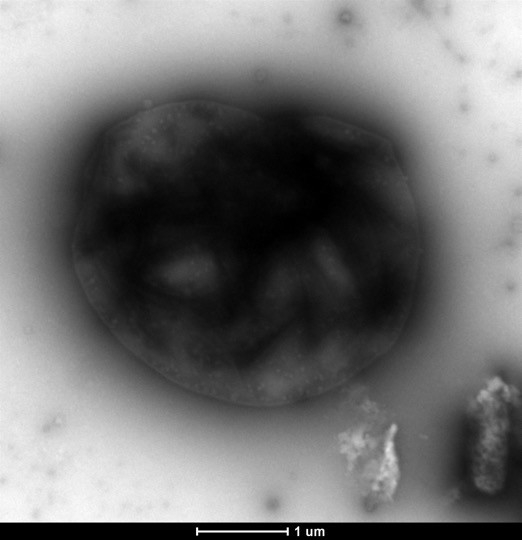

An ORNL-led team along with University of Michigan and Iowa State University investigated many different methanotrophs to single out how and which ones take up and break down methylmercury. Image by Jeremy Semrau, University of Michigan.

Scientists are tackling the methylmercury problem in the environment with a new microbial process that could reduce mercury toxicity levels and support health and risk assessments.

A team from the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory have discovered a new way to remove methylmercury—a neurotoxin that forms when mercury interacts with certain microbes in soil and waterways.

“Much attention has focused on mercury methylation or how methylmercury forms but few studies to date have examined microbial demethylation or the breakdown of methylmercury at environmentally relevant conditions,” Baohua Gu, co-author and a team lead in ORNL’s Mercury Science Focus Area, said in a statement.

Methylmercury accumulates at varying levels in fish—specifically large predatory fish, including tuna and swordfish. When consumed in large quantities, methylmercury can cause neurological damage and developmental disorders, particularly in children.

Methanotrophs—bacteria that feeds off methane gas and can either take up or break down methylmercury—are widespread in nature and exist near methane and air interfaces. Methane and methylmercury are both formed in similar anoxic—oxygen-deficient—environments.

The researchers, in a collaboration with methanotroph experts from the University of Michigan and Iowa State University, examined the behavior of several different methanotrophs and analyzed methylmercury uptake and decomposition using mass spectrometry.

This resulted in several methanotrophs, including Methlyosinus trichosporium OB3b, showed the ability to take up and break down methylmercury.

Others including Methylococcus capsulatus Bath, only showed the ability to take up methylmercury but not break it down.

However, in both cases the bacteria’s interactions lowered the mercury toxicity levels in water.

“If proven environmentally significant through future studies, our discovery of methanotrophs’ behavior could be a new biological pathway for degrading methylmercury in nature,” Gu said.