More than $150 billion in federal funding is invested in R&D annually in the United States. A key question is whether or not we are getting the maximum return on that investment.

Right now, the answer is that we could do better (1). Although technology transfer from 1996 to 2013 has contributed $518 billion to the U.S. gross domestic product and $1.1 trillion to the U.S. gross industrial output—with an impact of producing 3.8 million jobs for the U.S. economy(2)—there are still many promising new technologies in government and university laboratories with no clear path to commercialization.

Most technologies fail because they do not align with a market need, they are not economically viable or they are simply not mature enough for the marketplace. Yet many technologies waiting in the wings could have significant value in the commercial sector if only they received appropriate exposure or visibility to would-be receiving entities. A few may even have the potential to transform industries, disrupt traditional, out-of-date processes or solve critical problems for society.

Why is the path to commercialization slow, and sometimes tortuous, for these innovations? What can we do to smooth the way and accelerate the process of bringing new technologies and product ideas out of the lab and into the market? How can we derive a higher return on the invested billions of taxpayer dollars, drive economic development and support increased well-being for the world’s communities?

I recently had the privilege of moderating a panel at the 2018 R&D 100 Conference that explored these issues in depth. The Tech Scout Relay Panel brought together a stellar cast representing a diverse range of interests, backgrounds and organizations to discuss the challenges that come with identifying, channeling and leveraging emerging technologies into business opportunities. Our panelists included Dr. Terry Russell, Managing Director of Interface Ventures; Laura A. Schoppe, President of Fuentek LLC; George Gibson, Director of Technology Scouting at Xerox Corporation; and Jack G. Abid, Registered Patent Attorney with Allen, Dyer, Doppelt & Gilchrist, P.A.

One of the clear themes that emerged from this discussion was the significant need to build better and stronger bridges between different players in the innovation-to-commercialization pipeline. The organizations that are on the cutting edge of science and technology innovation are often not the ones best equipped to bring them to market, since their focus is research and not product development. Understanding what tech scouts, start-ups and established companies are looking for when they evaluate new technologies will help to bring innovators, investors and business partners together to smooth the path from lab to consumer.

The Technology Transfer Landscape: Many Players, Many Paths

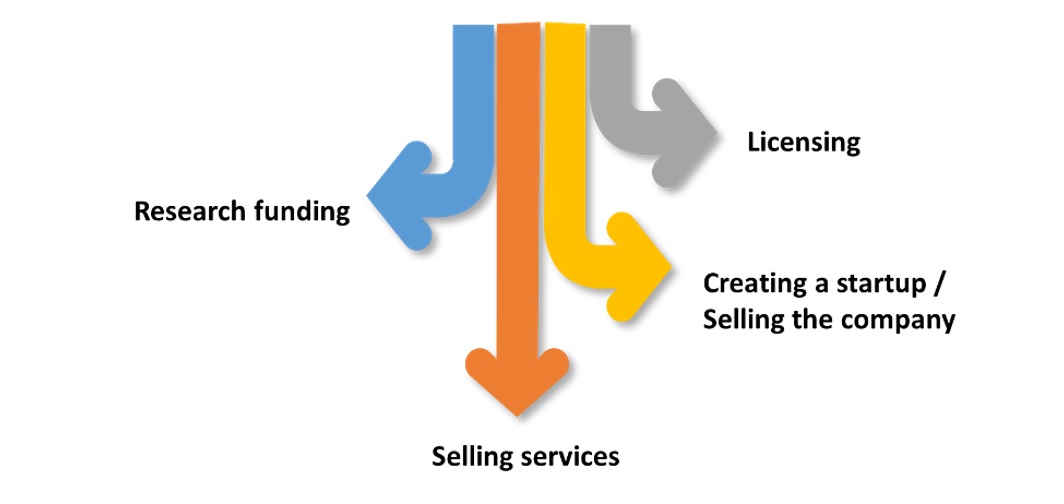

The technology transfer landscape can seem confusing and complex. Almost every organization practices the process in its own unique and customized way. As a result, there are multiple and varied paths to commercializing innovation, including traditional R&D (often using research grants), licensing someone else’s technology, creating a startup using venture capital, or delivering services through software and IT offerings or scaled-up manufacturing processes (3) that can generate immediate subscription revenue to fund continued development. Along the road, there are usually many different players involved in developing, discovering and commercializing new technologies. As Laura Schoppe explained in depth at the R&D 100 Conference panel discussion, each of these organization types has its own strengths, weaknesses and unique role to play in the overall architecture defining the technology transfer process.

Government Labs are still one of the primary movers when it comes to basic science and early-stage technology development. These entities have the resources and mission to pursue or fund foundational research that is often too expensive, too risky or has too little promise of immediate return to attract private funding. These government-funded labs pursue “big science” and research geared towards specific national priorities—such as national security, energy independence or public health—rather than focusing on market and/or consumer priorities.

However, this situation does not mean that the innovations coming out of government labs do not have market potential. Basic research funded through government labs often generates opportunities that are impossible to anticipate at their earliest stages, jump-starting entirely new platforms and industries such as the World Wide Web or the genomics industry. On the downside, these institutions can be slow and are not equipped to respond quickly to changing market demands or to take advantage of the commercial potential of the technologies which they develop. Government-funded research can also be erratic, changing focus with each change in government, thereby potentially impacting long-term research plans. Additionally, innovations that arise out of government-funded labs often need additional development work before they are suitable for a consumer or business-to-business (B2B) market.

Start-ups are naturally fast, nimble and responsive to market needs. They can be funded by private investors and venture capitalists, individual innovators, economic development grants or a combination of sources. No matter how they are formed, they need to move quickly to turn their initial investment money into a profit. Most will not have enough time and resources to conduct early-stage research and development. They are well suited to taking an early- or mid-stage technology, adapting it for a specific market niche, and introducing it to consumers or for B2B sale. Start-ups are often willing to take risks on unproven technologies in the hopes of hitting it “big” with product characteristics that no other competitor can match and introducing significant market disruption. However, they have a limited time to turn new products into profits before investors turn off the funding faucet. As Terry Russell said in his section of the panel, “A startup’s goal is to prove value.”

Established companies in the technology space usually have more resources than start-ups and are grounded in a proven portfolio of existing products, which generate profits that can be steered towards new development. Many of these companies reinvest profits into new R&D work. Most, however, are fairly risk adverse—they need to meet annual or quarterly financial targets to meet the expectations of shareholders, governing boards, and, most importantly, Wall Street. Many larger companies prefer to invest in a “sure” thing or make incremental improvements in already established technologies. They may also wait to acquire smaller start-ups that have already traversed the riskiest phase of product development and market introduction—often referred to as the “valley of death.” Larger companies, however, tend to have more resources, a longer sales cycle and greater marketing reach that can help to bring nascent technologies to a larger market if the innovation aligns with their longer-term strategic directions for growth.

Research organizations are typically universities but also include private and non-profit laboratories/institutions that focus on basic research rather than industry-sponsored research. These latter organizations—of which Battelle is one—often rely in large part on grants and government funding, yet they are not directly controlled or managed by government agencies. They may also provide contract research services for industry. Some, including Battelle, reinvest profits from contract work to support a variety of internally funded projects that are specifically designed to broaden scope, challenge the status quo and deliver innovation. These organizations operate in a middle space between profit-driven companies and mission-driven government labs. All of these research organizations, including universities, share a methodical and rigorous approach to research and tend to create early-stage technologies, yet usually do not have the resources (or perhaps even the capabilities, infrastructure and market channels) necessary to move innovations forward into full implementation and commercialization.

The Value of Research Organizations as Independent Tech Incubators

Each of these organization types fills an important role in the technology transfer landscape. Building better bridges between them will only help to accelerate the movement of new innovations to the market.

As Schoppe explained at the panel, government labs and research organizations can be tremendous assets for both start-ups and established companies. They reduce risks and sunk costs by providing companies with access to early-stage innovations that have already made it through the critical initial development period and sometimes testing. Because the technologies are not yet proven in the market, licensing fees tend to be lower than with more established technologies developed by industry. Research organizations also provide access to talent, subject matter expertise and specialized equipment and facilities that are beyond the reach of most companies. Finally, because these institutions are engaged in cutting-edge research, they can give the business sector a preview of tomorrow’s breakthrough innovations and identify the technologies and opportunities for which companies should be gearing up to watch closely.

Finding Alignment Between Organizations

Many research organizations are actively looking for commercialization partners who can help them take their ideas public—no innovator wants to see their hard work languish in a lab with no real-world applications. To make these partnerships work, both sides need to understand each other’s strengths, needs and priorities.

The first challenge is to identify the opportunity and determine the potential value for each organization. Russell explained some of the things that he looks for when scouting new technologies, including:

- A technology that has a clear, compelling and unique value proposition, and that addresses a real market need.

- Innovations that can be translated into products or services that support a marketing claim of “first, best or only.”

- A business plan that provides enough revenues to justify the investment and insulates the company from risks such as changing market conditions and competitive threats.

- A good technical team with solid IP protection and the potential to act as advisors or co-founders.

- Technology license terms that are reasonable and align with the startup’s business plan.

Russell says that, “Attempts on the part of licensing organizations to extract disproportionate early license fees or excess royalties act as headwinds on a startup.” He explains that this approach creates a situation “necessitating the raising of additional capital and leading to potentially lethal dilution of the initial stakeholders.”

Gibson discussed the challenges of aligning the business priorities, incentives and behaviors between different types of organizations and the individual participants on both sides. Research organizations may have very different incentives and behaviors than start-ups or established technology companies. Conversations between organizations should start with recognizing the differences between them and then establishing goals that take the needs of both sides into consideration. Perfect alignment may not always be possible, but the goal should be to create a contract with enough incentives for both sides to gain from the potential outcomes.

Economic considerations are always important, of course. Gibson stresses the importance of determining the potential value created by the new technology and ensuring that it justifies the costs of further development and a formal market launch. He says, “If there isn’t enough new value created to ‘feed’ everyone, it isn’t a real opportunity.”

If the value is there to justify commercialization, the final critical step is establishing the legal framework that will govern the relationship between organizations. There are many ways for research organizations and businesses to work together, from simple licensing agreements to extended joint ventures. Abid highlighted some of the key issues to consider when transferring intellectual property rights between non-profits and profit-based entities including:

- Ownership rights

- Permanent government rights (when research is government funded)

- Freedom to practice/manufacture rights

- Additional unknown licensees

- Obligations of contractor entities

Companies wishing to license or acquire technologies developed by research organizations or individual inventors will almost certainly need a lawyer well versed in patent law and intellectual property to guide the transaction and ensure a successful outcome. Abid says, “It is always less costly to deal with intellectual property rights upstream. Always verify existing intellectual property rights when scouting new technology, regardless of its source.”

Building Bridges to Bring Tomorrow’s Technologies to Market

If society is going to benefit from the value of continuing joint investment in basic research and new technologies, it is clear from the R&D 100 Conference panel discussion that we need to build stronger connections between the different players in the technology transfer marketplace, increase channels for exposure and develop attractive shared incentives. Non-profit research organizations and for-profit companies each have an important role to play in ensuring that emerging technologies reach the businesses and consumers that can benefit from them. This process can be nurtured by:

- Supporting and strengthening communication channels between the research community and the business community.

- Developing systematic methods for matching early stage technologies to opportunities and evaluating risk, market value, additional development requirements and other factors impacting the chances of successful commercialization.

- Simplifying and standardizing the process by which technology transfer is executed.

- Developing legal frameworks that meet the needs of all the organizations involved to smooth the way for successful ongoing collaboration.

Building these bridges will inevitably accelerate the technology transfer process and leave fewer promising early-stage technologies sitting in the lab. Working together towards creating stronger connections will be a win for research organizations, the commercial sector and society.

References:

- https://www.federallabs.org/news/nist-seeks-feedback-on-return-on-investment-initiative-draft-green-paper

- https://www.bio.org/sites/default/files/files/BIO_2015_Update_of_I-O_Eco_Imp.pdf

- https://www.kodak.com/US/en/corp/industrial-materials/default.htm

Vicki A. Barbur, PhD, is Senior Director, IP and Technology Commercialization, Commercial Business at BATTELLE, and she brings dual expertise in science and business as well as broad experience in several technical disciplines to her overarching role as an innovative growth leader associated with technology commercialization and IP management.