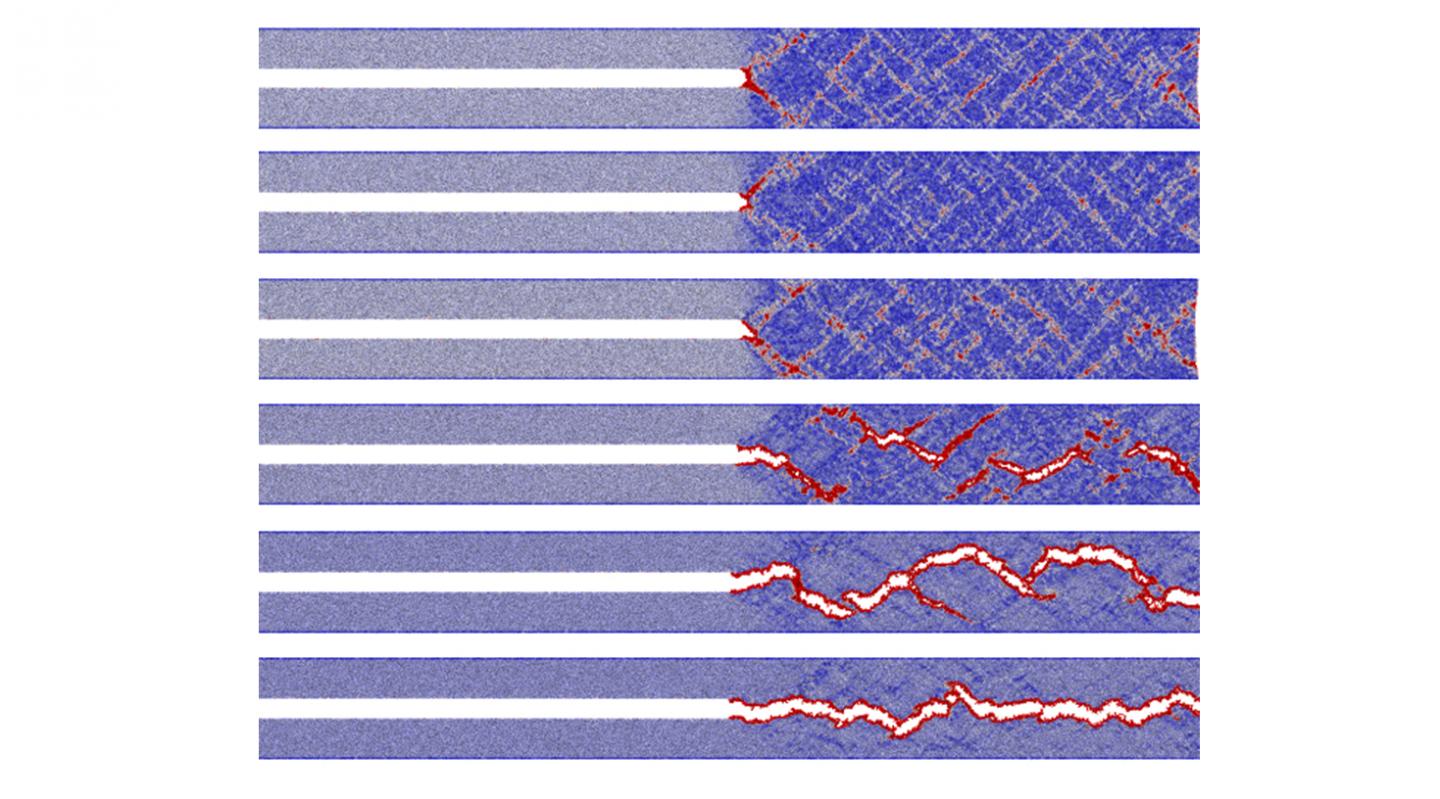

Measuring fracture energy in model glasses with various ductility; showing the deformation morphologies for glasses with various ductilities; and measured fracture energy (and normalized fracture energy by the surface energy). (Credit: Binghui Deng and Yunfeng Shi)

Metallic glasses — alloys lacking the crystalline structure normally found in metals — are an exciting research target for tantalizing applications, including artificial joints and other medical implant devices. However, the difficulties associated with predicting how much energy these materials release when they fracture is slowing down development of metallic glass-based products.

Recently, a pair of researchers from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, developed a new way of simulating to the atomic level how metallic glasses behave as they fracture. This new modeling technique could improve computer-aided materials design and help researchers determine the properties of metallic glasses. The duo reports their findings in the Journal of Applied Physics, from AIP Publishing.

“Until now, however, there has been no viable way of measuring a quality known as ‘fracture energy,’ one of the most important fracture properties of materials, in atomic-level simulations,” said Yunfeng Shi, an author on the paper.

Fracture energy is a fundamental property of any material. It describes the total energy released — per unit area — of newly created fracture surfaces in a solid. “Knowing this value is important for understanding how a material will behave in extreme conditions and can better predict how any material will fail,” said Binghui Deng, another author on the paper.

In principle, any alloy can be made into a metallic glass by controlling manufacturing conditions like the rate of cooling. To select the appropriate material for a particular application, researchers need to know how each alloy will perform under stress.

To understand how different alloys behave under different conditions, the researchers utilized a computational tool called molecular dynamics. This computer modeling method accounts for the force, position and velocity of every atom in a virtual system.

In addition, the calculations for the model are constantly updated with information about how the fractures spread throughout a sample. This type of heuristic computer learning can best approximate real-world conditions by accounting for random changes like fractures in a material.

Their model accounts for the complex interplay between the loss of stored elastic energy from an erupting fracture, and how much the newly created surface area of the crack compensates for that energy loss.

“Computer-aided materials design has played a significant role in manufacturing and it is destined to play far greater roles in the future,” Shi said.