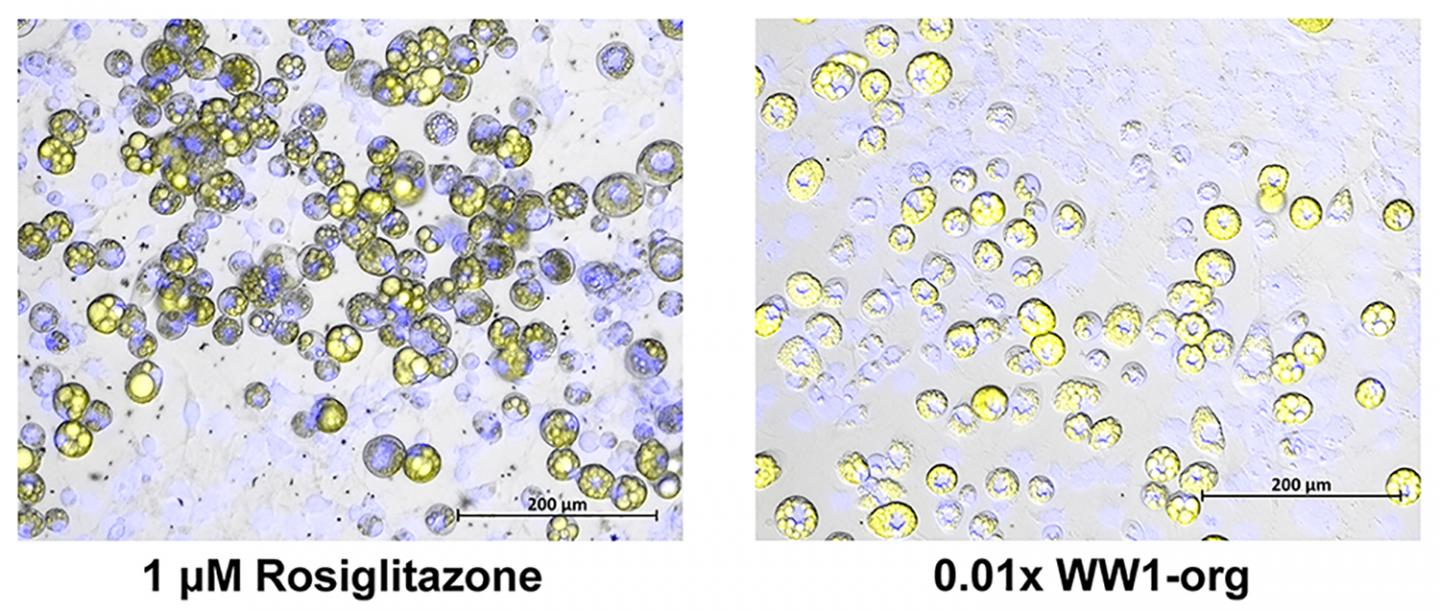

Duke scientists used cells in culture to test samples of fracking wastewater and contaminated surface water. On the left, a drug called rosiglitazone is known to create fat cells and cause weight gain. On the right, diluted fracking wastewater. Yellow marks accumulation of fat within cells. Blue marks new fat cells being created. Credit: Chris Kassotis, Duke University

Researchers from Duke University found that exposure to fracking chemicals and wastewater promotes fat cell development, called adipogenesis, in living cells.

The researchers discovered an increase in the size and number of fat cells after they exposed living mice cells in a dish to a mixture of 23 chemicals commonly used in fracking operations.

The team also saw the same effects after they exposed the cells to samples of wastewater from fracked oil, gas wells and surface water that was contaminated by the wastewater.

“We saw significant fat cell proliferation and lipid accumulation, even when wastewater samples were diluted 1,000-fold from their raw state and when wastewater-affected surface water samples were diluted 25-fold,” Chris Kassotis, a postdoctoral research associate at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, said in a statement. “Rather than needing to concentrate the samples to detect effects, we diluted them and still detected the effects.”

In the study, the researchers collected samples of fracking wastewater and wastewater-contaminated surface water near fracked oil and gas production sites in Garfield County, Colorado and Fayette County, West Virginia.

The researchers then exposed laboratory cultures of mouse cells to the waters at varying concentrations, or dilutions, over a two-week period and measured how fat cell development in the cultures was affected. They performed similar tests exposing cell models to the mix of 23 fracking chemicals.

The team exposed other cells within each experiment to a pharmaceutical that is highly effective at activating fat cell differentiation and causing weight gain in humans, known as rosiglitazone.

After exposing the cells, they found that the 23-chemical mix induced 60 percent as much fat accumulation as the pharmaceutical, the diluted wastewater samples induced 80 percent as much and the diluted surface water samples induced about 40 percent as much.

In all three cases, the amount of precursor fat cells that developed was greater in cell models exposed to the chemicals or water samples than in those exposed to the rosiglitazone.

“Activation of the hormone receptor PPAR-gamma, often called the master regulator of fat cell differentiation, occurred in some samples, while in other samples different mechanisms such as inhibition of the thyroid or androgen receptor, seemed to be in play,” Kassotis said.

Researchers have previously found that rodents exposed to 23 fracking chemicals during gestation are more likely to experience metabolic, reproductive and developmental health impacts that include increased weight gain.

The team now plans to assess whether similar effects occur in humans or animals who drink or come into physical contact with affected surface waters outside the laboratory.

More than 1,000 different chemicals are used for hydraulic fracturing across the United States, many that have been demonstrated through laboratory testing to act as endocrine disrupting chemicals in both cell and animal models.

The study was published in Science Direct.