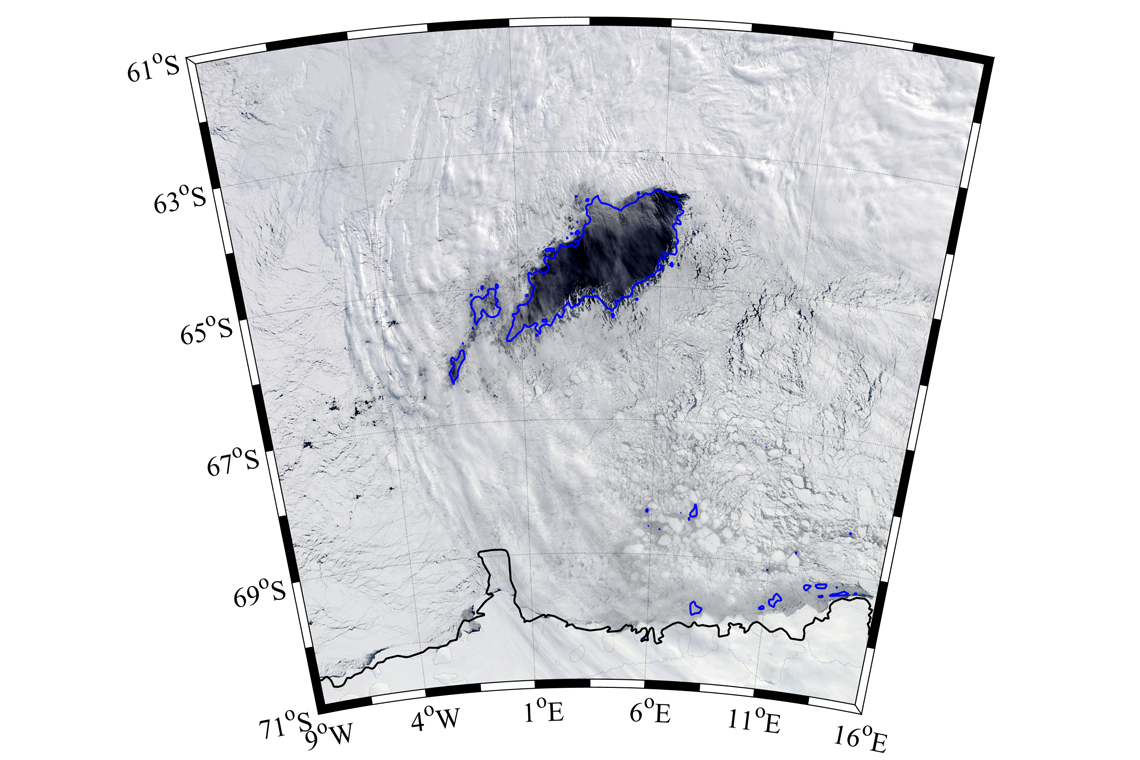

Winter sea ice blankets the Weddell Sea around Antarctica, with the hole or polynya being the dark region of open water within the ice pack (image from MODIS-Aqua via NASA Worldview)

A hole the size of one of the Great Lakes found in Antarctica has researchers scratching their heads.

While substantial holes in the icy surface of Antarctica called polynyas are not uncommon, they are generally confined to the coastal regions.

However, an international team of scientists have discovered a mysterious, 31,000 square mile hole (80,000 square kilometers)—the size of Lake Superior— making it the biggest polynya observed in Antarctica’s Weddell Sea, which has researchers confounded.

“In the depths of winter for more than a month, we’ve had this area of open water,” Kent Moore, a professor of atmospheric physics at the University of Toronto Mississauga told National Geographic. “It’s just remarkable that this polyna went away for four years and then came back.”

The researchers believe the polynya may have been formed because of the deep water in the Southern Ocean being warmer and saltier than the surface water.

Ocean convection occurs in the polynya when warmer water comes to the surface and then melts the sea ice and prevents new ice from forming.

A team that includes researchers from the University of Toronto and the Southern Ocean Carbon and Climate Observations and Modelling (SOCCOM) group at Princeton University are monitoring the area with satellite technology and using robotic floats that are capable of operating under sea ice to finally shed some light on the polynya and their impact on the climate.

According to researchers from the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, who first discovered the polymya, it is currently in the middle of the winter season in Antarctica and the Weddell Sea is usually covered by a thick layer of sea ice.

“For us this ice-free area is an important new data point which we can use to validate our climate models,” Torge Martin, Ph.D., a meteorologist and climate modeler for GEOMAR, said in a statement. “Its occurrence after several decades also confirms our previous calculations.”

The hole first showed up on satellite images on Sept. 9 and the researchers said it would be premature to blame the polynya on climate change.

“The Southern Ocean is strongly stratified. A very cold but relatively fresh water layer covers a much warmer and saltier water mass, thus acting as an insulating layer,” Mojib Latif, Ph.D., head of the Research Division at GEOMAR, said in a statement. “This is like opening a pressure relief valve–the ocean then releases a surplus of heat to the atmosphere for several consecutive winters until the heat reservoir is exhausted.”