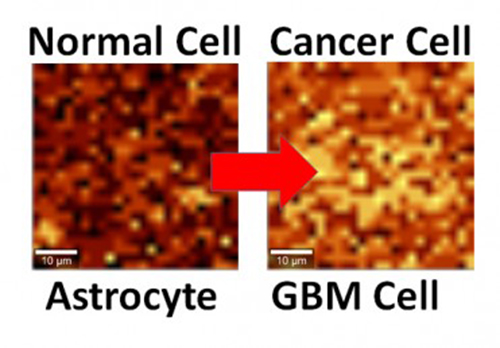

Normal and cancerous brain cells interfaced with graphene show different activity levels under Raman imaging. Image: UIC/Vikas Berry

What can’t graphene do? You can scratch “detect cancer” off of that list.

By interfacing brain cells onto graphene, researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago have shown they can differentiate a single hyperactive cancerous cell from a normal cell, pointing the way to developing a simple, noninvasive tool for early cancer diagnosis.

“This graphene system is able to detect the level of activity of an interfaced cell,” says Vikas Berry, associate professor and head of chemical engineering at UIC, who led the research along with Ankit Mehta, assistant professor of clinical neurosurgery in the UIC College of Medicine.

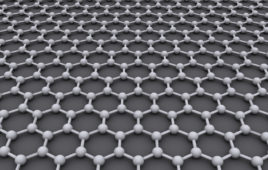

“Graphene is the thinnest known material and is very sensitive to whatever happens on its surface,” Berry says. The nanomaterial is composed of a single layer of carbon atoms linked in a hexagonal chicken-wire pattern, and all the atoms share a cloud of electrons moving freely about the surface.

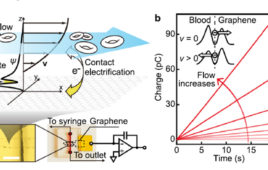

“The cell’s interface with graphene rearranges the charge distribution in graphene, which modifies the energy of atomic vibration as detected by Raman spectroscopy,” Berry says, referring to a powerful workhorse technique that is routinely used to study graphene.

The atomic vibration energy in graphene’s crystal lattice differs depending on whether it’s in contact with a cancer cell or a normal cell, Berry says, because the cancer cell’s hyperactivity leads to a higher negative charge on its surface and the release of more protons.

“The electric field around the cell pushes away electrons in graphene’s electron cloud,” he says, which changes the vibration energy of the carbon atoms. The change in vibration energy can be pinpointed by Raman mapping with a resolution of 300 nanometers, he says, allowing characterization of the activity of a single cell.

The study, reported in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, looked at cultured human brain cells, comparing normal astrocytes to their cancerous counterpart, the highly malignant brain tumor glioblastoma multiforme. The technique is now being studied in a mouse model of cancer, with results that are “very promising,” Berry says. Experiments with patient biopsies would be further down the road.

“Once a patient has brain tumor surgery, we could use this technique to see if the tumor relapses,” Berry says. “For this, we would need a cell sample we could interface with graphene and look to see if cancer cells are still present.”

The same technique may also work to differentiate between other types of cells or the activity of cells.

“We may be able to use it with bacteria to quickly see if the strain is Gram-positive or Gram-negative,” Berry says. “We may be able to use it to detect sickle cells.”

Earlier this year, Berry and other coworkers introduced nanoscale ripples in graphene, causing it to conduct differently in perpendicular directions, useful for electronics. They wrinkled the graphene by draping it over a string of rod-shaped bacteria, then vacuum-shrinking the germs.

“We took the earlier work and sort of flipped it over,” Berry says. “Instead of laying graphene on cells, we laid cells on graphene and studied graphene’s atomic vibrations.”

Co-authors on the study are Bijentimala Keisham and Phong Nguyen of UIC chemical engineering and Arron Cole of UIC neurosurgery.

Funding was provided by UIC.