Macrophages become the preferential biological niche in some bacterial strains to replicate and spread around the body.

An international team led by the University of Barcelona has identified a new antibacterial mechanism that protects macrophages — defense cells in the immune system — from the infection of the bacteria Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, a pathogen associated with several gastrointestinal diseases. This discovery, carried out with mice and published in the journal Cell Reports, is led by Professor Annabel Valledor, from the Faculty of Biology of the University of Barcelona, and could open new exploration channels for pharmacological treatments of some bacterial infections.

Other co-authors of this study are the experts Jonathan Matalonga, Estibaliz Glaria, José María Carbó, Theresa León, Mònica Pascual, Samantha Morón, Sònia Paytubi, and Antonio Juarez (Faculty of Biology); Antoni Riera (Faculty of Chemistry and IRB Barcelona); Carme Caelles (Faculty of Pharmacy and Food Sciences); Fernando Sotillo (IRB Barcelona); Joan Serret (PCB), Carlos Escande (Institut Pasteur, Uruguay); Susana Beceiro and Antonio Castrillo (“Alberto Sols” Biomedical Research Institute, Madrid) and Eduardo N. Chini (Mayo Clinic), among others.

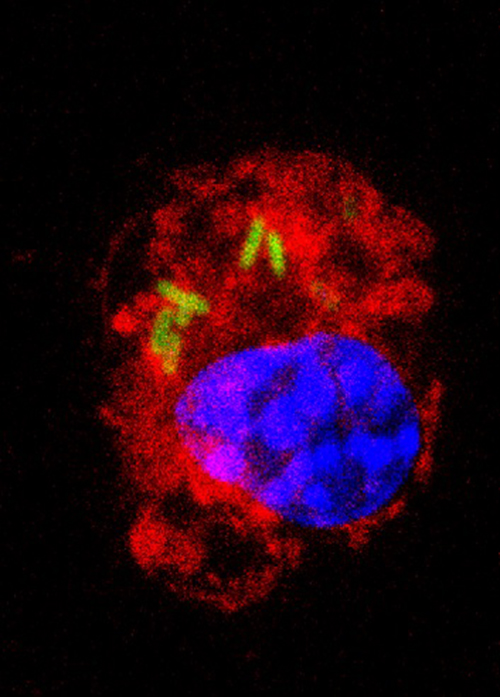

Macrophages are specialized cells in the immune system with diverse effector functions against pathogens and invasive agents. However, although it seems a paradox, they become the preferential biological niche in some bacterial strains to replicate and spread around the body.

This is the case, for instance, of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, an enteric bacterium that causes from mild gastroenteritis to severe systemic infections in humans. This strain, in particular, is able to survive and replicate inside the host macrophages as a previous step to spread around the other parts of the body.

S. Typhimurium avoids the bactericidal response so that after adhering to the surface of the macrophage, it secretes factors that modify the F-actin cytoskeleton of the host cell. This mechanism allows the bacteria entering the cell through special phagocytic vacuoles (containing Salmonella). Once they enter the cell, the bacterium transforms the vacuole’s conditions to turn it into a favorable environment to replicate and spread around the infected organism.

In the new study, the scientific team describes a mechanism that limits the capacity of S. Typhimurium to infect cells and spread in other tissues. “Our study reveals that pharmacological activation of transcription factors from the family of nuclear receptors — Liver X receptors or LXR — limits the bacterial infection in macrophages,” says Professor Annabel Valledor, who leads the Group Nuclear receptors in Cancer, Metabolism, and Inflammation of Nurcamein network.

Nuclear receptors are transcription factors that shape physiological processes through the regulation of the gene expression of several targeted genes. LXR, in particular, can be activated by agonists (molecule activators) and play an important role in metabolic functions and the regulation of the immune response.

In this case, LXRs regulate the transcriptional activation of the multifunctional enzyme CD38, distributed in cells in the immune system, and which has a potent NAD+ activity, which is a metabolite associated with the energy cell mechanism.

“Through this mechanism, the treatment with LXRs agonists is able to lower the intracellular levels of NAD+, a process which interferes in a series of morphological and distribution changes in the macrophage’s F-actin cytoskeleton and is used for their own benefit in certain invasive bacteria.”

The LXRs pharmacological activation, thus, inhibits the S. Typhimurium capacity to infect cells and get to other parts of the body, and contributes to improve the clinical symptomatology in laboratory animals infected by this enteric bacterium.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), resistance to antibiotics is one of the big threats for world health, food safety and world development. Despite being a natural phenomenon, bacterial multi-resistance is speeding up due the excessive and wrong use of drugs. As a consequence, there are more and more infections that don’t respond to the common treatments due antibiotics losing their efficacy.

“Facing the dangers that involve the apparition of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains (more common every day), this new research study established the path of LXRs as a new mechanism in the regulation of the host-pathogen interaction which could be pharmacologically exploited as a potential strategy of “host-directed therapy” in certain bacterial infections,” concludes Valledor.

Source: University of Barcelona